Egypt has placed a high-end Turkish combat drone model at a remote southern airstrip close to the Sudan border, an action multiple officials and regional experts say signals a marked intensification of regional involvement in Sudan's civil war. The deployment, revealed through satellite imagery and corroborated by analysts who examined the images, suggests Cairo is moving beyond political support to more direct military posture to protect perceived national security interests.

Egypt and Sudan share both the Nile and a border that stretches more than 1,200 kilometres. For much of the nearly three-year-long conflict between Sudan's Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Cairo largely provided political backing to the Sudanese military and, according to some Egyptian security officials, limited logistical and technical assistance. Direct intervention in combat operations, however, was mostly avoided until recent months.

Escalation linked to RSF gains in Darfur

Multiple regional analysts and diplomats briefed by Egyptian officials traced the shift in Cairo's posture to a series of RSF advances in the western Darfur region. Those advances included capture of a strategic northwestern triangle between Egypt and Libya in June, followed by the RSF's takeover of al-Fashir, the Sudanese military's last stronghold in Darfur, in October. The fall of al-Fashir was repeatedly cited by analysts as a turning point that made Egypt reassess its prior, more restrained position.

In December, Egypt’s presidency publicly stated that the country's national security is directly tied to developments in Sudan and warned that it would not permit certain "red lines" to be crossed. The presidency defined those red lines to include preserving Sudan’s territorial integrity and rejecting any "parallel entities" that might threaten national unity.

Satellite imagery, drone identification and airstrip upgrades

Two Egyptian security officials told observers that two southern airports have received military equipment over about the past eight months to secure the border and to carry out strikes deemed necessary for "national security". The officials spoke on condition of anonymity and provided no operational details.

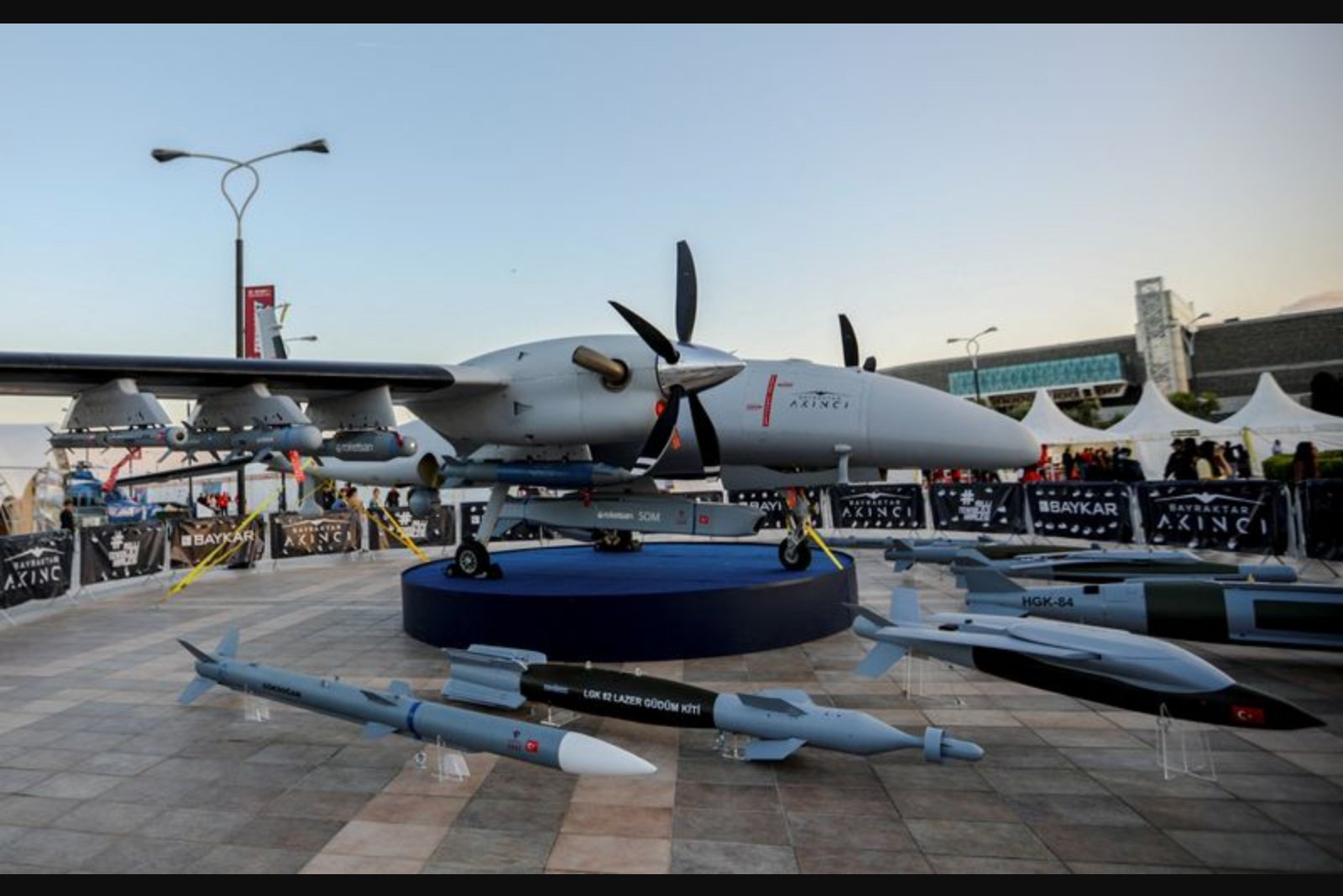

Satellite pictures from a U.S. space technology company show a large drone on the apron at the East Oweinat airport on September 29, December 28 and January 9. Two military experts who reviewed those images identified the aircraft as a Bayraktar Akinci, based on its distinctive fuselage and wing design. A separate outlet has also published imagery of Akinci drones at East Oweinat, reporting they were used for strikes in Sudan.

The Akinci, manufactured by Turkish defence firm Baykar, is among the company's most advanced models. It is noted for its ability to reach high altitudes, remain airborne for up to 24 hours and carry a variety of munitions, according to descriptions in imagery analyses and defence commentary.

Imagery specialists and analysts who reviewed satellite photos also noted signs of physical upgrades to the East Oweinat airstrip between early July and the end of January. Those works included repaving of the runway and possible slight widening, the addition of smaller access roads, evidence of excavation and construction, and the appearance of at least two small new structures. Observers interpreted the presence of support equipment and material around the drones, and their placement in different locations on the airfield, as indicators that the aircraft were operational rather than merely parked.

Numbers and sightings

While most imagery clearly shows only a single Akinci on a given day, a Planet Labs image taken on December 28 was judged by a regional defence analyst to almost certainly display two of the drones outside one hangar. In other images Akincis appeared outside multiple hangars, implying more than one airframe was present and that some hangars were used to store aircraft when not flying.

The RSF has asserted that Akincis have repeatedly attacked areas under its control and claims its fighters shot down at least seven of the drones since June, although those claims could not be independently verified. Two social media videos posted in mid-January that the RSF attributed to a downed Akinci near Nyala, its main Darfur stronghold, were assessed by two military experts as showing wreckage consistent with a crashed Akinci. The timing and location of those videos could not be independently established, and it was not possible to determine who was operating the aircraft in those instances.

Flight activity linking Turkey and East Oweinat

Open flight tracking data show five of six flights into East Oweinat since September had origins in Turkey. Three of these were cargo flights operated by the Turkish Air Force from Tekirdag, the Turkish city where Akinci models are tested, on December 25, December 26 and January 7. The contents of those flights were not determined from publicly available tracking information.

Separately, Turkish officials have publicly discussed drone sales to Egypt. In February 2024 the Turkish foreign minister said Ankara would sell drones to Cairo as ties between the two countries normalized, without specifying the models. A source at the Turkish Defence Ministry later said an agreement had been reached the same year on the sale of Akincis but did not provide further specifics. A Western diplomat who meets with Turkish officials said Turkey had privately defended Egyptian airstrikes on the RSF as legitimate and confirmed recent deliveries of drones for use in the conflict, while declining to provide details.

Claims of Egyptian strikes and denials

The RSF's leader has accused Egypt of involvement in airstrikes against his forces since at least October 2024. Egyptian authorities denied those allegations at the time. Separately, a regional news outlet quoted an Egyptian military official as saying Egypt carried out an airstrike on an RSF convoy in the border triangle area on January 9. A diplomat who had been briefed by Egyptian officials said that strike was launched from a southern Egyptian airbase. Those accounts have not been independently verified.

Egypt’s Foreign Ministry and State Information Service did not answer questions about operations at East Oweinat or activities in Sudan. Sudan’s military also did not provide comment to requests for information.

Regional array of foreign involvement

The conflict in Sudan, which erupted into open confrontation between the military and the RSF in April 2023 over force-integration plans tied to a transition to civilian rule, has drawn in a range of foreign actors. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and the United States have been described as the cluster of countries most influential in the crisis and have attempted, without success, to broker ceasefires.

UN experts have accused the UAE of providing weapons to the RSF, an allegation Abu Dhabi denies. Sudan’s military has deployed Turkish and Iranian drones and has received political backing from Qatar and Saudi Arabia. The RSF leader has publicly warned that aircraft taking off from "airports in neighboring countries" attacking his forces would be considered a "legitimate target" for his fighters.

An Emirati official stated that the UAE is working with regional partners - including Egypt and Saudi Arabia - to secure a ceasefire in Sudan and said the UAE's decisions have "consistently favoured restraint over escalation". Saudi authorities did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Strategic geography and Egypt's security calculus

Analysts and a retired Egyptian military officer said East Oweinat is a main base through which Cairo can seek to secure its southern borders. The airstrip lies roughly 60 kilometres from the Sudan border in a remote agricultural area and was originally used to support a desert reclamation project before the outbreak of war.

Samir Farag, a retired Egyptian military officer, described the airstrip as a key location for protecting Egypt's southern approaches. "Egypt doesn’t allow anyone to be present on its borders and threaten its national security," he said. "It will intervene directly and manage the situation. This is the right of every country in the world."

Justin Lynch, managing director of a consultancy that tracks the Sudan conflict closely, said the deployment of drones at East Oweinat was "an indication of Egypt’s recent policy to be more involved in Sudan". The airport is less than 400 kilometres from Sudan’s border triangle, a region of strategic sensitivity where the RSF has been able to receive supplies from southeastern Libya bound for Darfur. That logistical corridor was cited by analysts as instrumental to the RSF’s advance on al-Fashir.

Commentators who study the conflict noted Egypt's military has no affinity for the RSF but must balance that hostility with its dependence on financial ties with the UAE, a major backer of the RSF. The fall of al-Fashir, and the atrocities the RSF has been accused of in its wake, were identified by analysts as having shifted Cairo's equilibrium toward tougher measures against the RSF.

Some analysts also suggested that Saudi Arabia's moves to limit UAE influence in Yemen may have influenced dynamics in the wider region, including calculations around Sudan, with rivalries spilling over into the Horn of Africa.

Operational indicators and uncertainty

Analysts point to several operational indicators at East Oweinat: multiple satellite images showing one or more Akincis on different dates, support equipment and loading materials surrounding the aircraft, and visible runway and facility upgrades. These features together suggest the airstrip is being prepared and used for ongoing operations.

Still, several important questions remain unanswered publicly. Egyptian authorities have not confirmed operations from the airstrip or the presence of Akincis, and independent verification of reported strikes attributed to aircraft from neighboring countries has not been possible. The RSF’s claims about downed drones have not been verified, and the operators in individual incidents could not be determined from available open-source footage.

Conclusion

The placement of advanced Turkish-made Akincis at a remote airport within striking distance of Sudan’s most contested western provinces marks a tangible intensification of Egypt’s posture toward the conflict. Satellite imagery, flight-tracking records and statements from analysts and officials combine to show a recent pattern of activity at East Oweinat consistent with preparations for and execution of cross-border military operations, though several elements remain publicly unconfirmed.

As the conflict draws in multiple regional and international actors and as supply corridors and contested border zones come under pressure, the situation in Sudan continues to evolve in ways that regional capitals are monitoring closely. Cairo’s move to position advanced drones at a southern airstrip underscores the ties Cairo views between developments in Sudan and its own national security thresholds.