Vertical spreads occupy a central place in options strategy because they deliver defined risk, defined potential reward, and relatively stable sensitivity to volatility. Constructed from two options of the same type and expiration but different strikes, they compress the open-ended payoff of a single option into a bounded profile that can be analyzed, standardized, and repeated. The result is a structure that lends itself to systematic rules across underlyings and market conditions without relying on ad hoc judgment.

Definition and Basic Structure

A vertical spread combines either two calls or two puts on the same underlying with the same expiration. One option is purchased and the other is sold, and the strikes differ. The relative position of the strikes determines the directional bias, and the net premium determines whether the position is a debit or a credit.

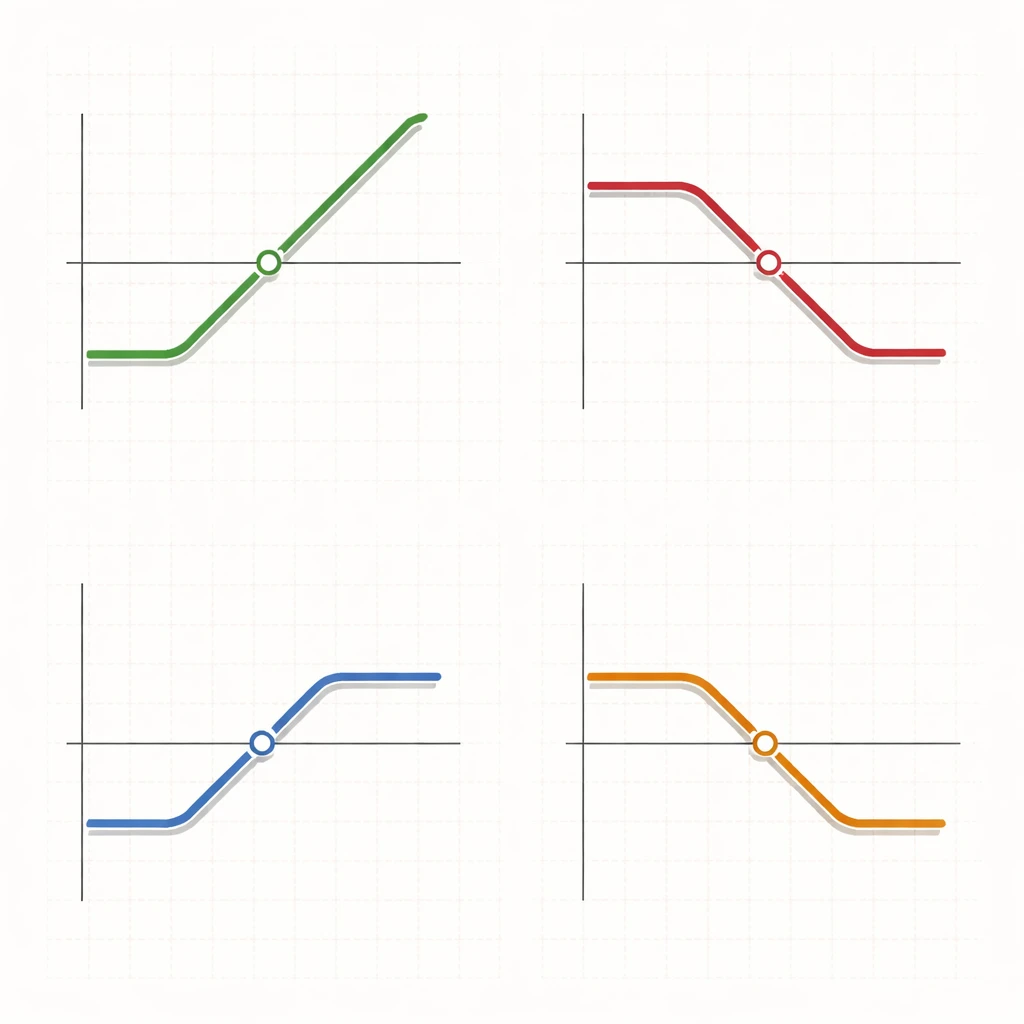

- Bull call spread: buy a lower strike call and sell a higher strike call. Net debit. Directional bias is moderately bullish.

- Bear call spread: sell a lower strike call and buy a higher strike call. Net credit. Directional bias is neutral to bearish.

- Bear put spread: buy a higher strike put and sell a lower strike put. Net debit. Directional bias is moderately bearish.

- Bull put spread: sell a higher strike put and buy a lower strike put. Net credit. Directional bias is neutral to bullish.

These four variants share a common blueprint: the long leg defines protection against adverse moves, while the short leg finances part of the cost or generates credit in exchange for capping potential gains. Because both legs share the same expiration, the payoff at expiry is piecewise linear and easy to standardize across different underlyings.

Core Logic and Economic Intuition

The core logic of a vertical spread is to exchange the unlimited upside or downside of a single long or short option for a defined range of outcomes. This exchange introduces a structured balance among three forces: direction, time, and volatility.

- Direction: A bull spread benefits when the underlying price moves higher within a defined range. A bear spread benefits when the price moves lower within a defined range. The slope of the payoff with respect to the underlying price is the spread’s net delta, which is smaller in magnitude than that of a single option because the long and short legs partially offset.

- Time: Time decay, or theta, works differently depending on net debit or net credit. Debit spreads start with negative theta, since you pay premium, but the short leg reduces the magnitude of decay compared with a lone long option. Credit spreads begin with positive theta, since you receive premium, but the long protective leg offsets some of that positive decay.

- Volatility: Vertical spreads have lower net vega than single long or short options. The short leg partially neutralizes volatility exposure from the long leg. As a result, verticals are less sensitive to implied volatility shocks, which makes them attractive for rule-based deployment where stability of exposure is desirable.

Because the maximum loss and maximum profit can be stated in advance, and because the paths to those outcomes are bounded by strike selection, vertical spreads provide a clean framework for defining risk per position and for calibrating portfolios to a target risk budget.

Payoff Characteristics

The payoff characteristics of vertical spreads are straightforward at expiration and more nuanced before expiration.

At Expiration

- Debit verticals (bull call or bear put): maximum loss equals the net premium paid. Maximum profit equals the distance between strikes minus the net premium paid. The breakeven price is the long strike adjusted by the net premium per share. For a bull call spread that means the lower strike plus the debit. For a bear put spread that means the higher strike minus the debit.

- Credit verticals (bear call or bull put): maximum profit equals the net premium received. Maximum loss equals the distance between strikes minus the net premium received. The breakeven price is the short strike adjusted by the net premium per share. For a bear call spread that means the short call strike plus the credit. For a bull put spread that means the short put strike minus the credit.

These relationships illustrate why verticals fit systematic approaches. Every trade specifies its worst-case loss and capped profit the moment strikes are chosen. That enables consistent sizing and pre-defined exits.

Before Expiration

Before expiration, mark-to-market values reflect not only underlying price but also time remaining and implied volatility. Several tendencies are useful for structuring rules:

- Convergence to intrinsic value: As time passes, the extrinsic component shrinks. Debit spreads whose directional thesis is correct tend to approach their maximum value, while credit spreads whose thesis is correct tend to decay toward zero.

- Changing delta: A vertical’s net delta changes as the underlying moves. When price approaches the profitable side of the spread, delta approaches zero for credit spreads and approaches zero or a smaller positive or negative number for debit spreads as the payoff flattens near maximum value.

- Vega dampening: The opposite vega exposures of the legs temper the portfolio’s reaction to volatility changes. A sudden volatility increase typically helps debit verticals and hurts credit verticals, all else equal, but the effect is muted relative to single-leg positions.

Constructing Vertical Spreads Step by Step

Although no exact entry details are provided here, the construction steps are universal:

- Select the underlying and a single expiration date.

- Choose call or put based on directional thesis.

- Pick the long and short strikes to target a defined risk and reward profile. Strike spacing sets the maximum profit in debit spreads and the maximum loss in credit spreads.

- Confirm liquidity and execution quality. Bid-ask spreads, open interest, and volume affect slippage and realized outcomes.

- Estimate the spread’s greeks to understand sensitivity to price, time, and volatility, and to gauge portfolio interactions with other positions.

Because each step translates into clear parameters, they can be encoded into a repeatable checklist or algorithm and applied consistently across instruments.

Debit Versus Credit: Structural Differences

Debit and credit verticals express similar directional ideas but with distinct capital and sensitivity profiles.

- Capital outlay: Debit verticals require upfront premium and have no margin requirement beyond that premium. Credit verticals receive premium but require margin equal to the maximum potential loss, less credit received.

- Profit path: Debit verticals seek movement toward the profitable side, often benefitting when implied volatility rises. Credit verticals profit mainly from time decay and from the underlying price staying away from the short strike, often benefitting when implied volatility falls.

- Payoff cap: Both are capped. The width of the spread sets the cap; net debit or credit shifts the payoff up or down but cannot exceed the width minus consideration paid or received.

- Greeks: Debit verticals tend to have lower absolute theta and vega than a single long option. Credit verticals tend to have positive theta but also carry negative convexity in the region near the short strike as expiration approaches.

Risk Management Considerations

Vertical spreads simplify risk management because the worst-case loss can be known at entry. However, several practical risks require explicit procedures.

Position Sizing

Defined risk allows position size to be anchored to a fixed dollar loss budget per trade or per portfolio. In a rules-based system, size can vary directly with the distance between strikes, the net debit or credit, or a combination that targets a constant maximum loss per spread. Consistency in sizing reduces variance in portfolio outcomes across trades.

Liquidity and Slippage

Spreads add transaction complexity relative to single options. Wide bid-ask spreads, low open interest, and partial fills can distort realized results. Good practice includes using liquid underlyings, preferring tighter spreads, and considering limit pricing for the package rather than legging one side at a time. Slippage planning belongs in the system design stage, not at order entry.

Early Assignment and Exercise

American-style options carry assignment risk for the short leg before expiration, particularly near ex-dividend dates for calls or when time value collapses. A repeatable process should specify how to handle early assignment scenarios, including whether to hold, close, or exercise the long leg if assignment occurs. The presence of the long leg limits the ultimate risk, but operational frictions can still matter.

Expiration Management and Pin Risk

On expiration day, prices can hover near the short strike. Small moves can change intrinsic value at the bell, creating pin risk. Systems can reduce exposure by closing or adjusting spreads ahead of expiration based on pre-set time or value criteria. If a leg expires in the money, brokers may exercise or assign automatically. Procedures must account for after-hours price moves that could transform the position after the close.

Correlation and Portfolio Construction

A vertical spread’s defined risk does not eliminate portfolio-level risk concentration. Multiple spreads on highly correlated assets can create large directional exposures that move together. Diversification across sectors, expirations, and strike locations, combined with aggregate delta and vega monitoring, helps preserve system robustness.

Regulatory and Operational Constraints

Margin requirements, pattern day trading rules, and settlement conventions differ across markets and brokers. Tax treatment of options varies by jurisdiction. A systematic playbook should be written with these constraints in mind and tested in the specific environment where it will be used.

How Vertical Spreads Fit Structured, Repeatable Systems

Vertical spreads are amenable to rules-based implementation because key inputs are discrete and observable. A system can define when to consider a spread, how to select strikes, when to exit, and how to size, all without forecasting precise price targets.

Standardizing Setup Parameters

- Expiration window: Systems often confine selections to a consistent range of days to expiration. This stabilizes theta decay profiles and simplifies comparisons across trades.

- Strike width: Fixing or bounding the distance between strikes standardizes maximum loss and maximum profit per spread and simplifies portfolio budgeting.

- Moneyness rules: Rules can specify whether to use out-of-the-money, at-the-money, or slightly in-the-money legs based on measured characteristics like realized volatility or average true range, expressed in non-prescriptive terms.

Entry Filters and Validation

Systems can require minimum liquidity thresholds, cap bid-ask spreads, or demand a minimum open interest at both strikes. They can also require confirmation criteria such as trend filters or volatility regimes, defined without soliciting precise signals here. The point is to codify repeatable checks that are applied consistently.

Exit and Lifecycle Rules

Exits can be expressed as time-based or value-based without reference to exact numbers. Time-based exits might close positions a set number of days before expiration to mitigate pin and assignment risk. Value-based exits might target a fraction of maximum profit or limit realized loss to a fraction of maximum loss. These rules translate the payoff geometry into operational discipline.

Monitoring and Review

Tracking realized outcomes against their theoretical bounds is essential. Because vertical spreads have clear ceilings and floors, discrepancies often reflect execution quality, slippage, or volatility shifts. System reviews can compare pre-trade expectations for theta decay and delta exposure with post-trade outcomes to refine rules, not to chase performance.

High-Level Examples

Example 1, Bullish Thesis with a Debit Spread

Consider an underlying trading near a round-number level. A trader with a moderate bullish thesis chooses a bull call spread by buying a lower strike call and selling a higher strike call with the same expiration. The position is opened for a net debit. The rationale is to reduce upfront cost relative to a single long call and to cap the upside at the higher strike. The maximum loss equals the debit paid, which is realized if the underlying finishes at or below the lower strike at expiration. The maximum profit equals the distance between strikes minus the debit, which is realized if the underlying finishes at or above the higher strike at expiration.

Operationally, the trader expects that a move higher within the life of the option will lift the spread’s value. If implied volatility rises, the long call benefits more than the short call loses, though the effect is reduced by the offsetting legs. If price stalls, time decay erodes the spread’s value, but less so than a lone long call would have experienced. A rules-based exit could remove the position several days before expiration to avoid pin risk or could close earlier if a pre-defined fraction of maximum value is reached, though exact thresholds are not specified here.

Example 2, Neutral to Bullish Thesis with a Credit Spread

Consider a neutral to slightly bullish thesis. A bull put spread is constructed by selling a higher strike put and buying a lower strike put in the same expiration for a net credit. Maximum profit equals the credit received, realized if the underlying finishes at or above the short put strike at expiration. Maximum loss equals the strike distance minus the credit, realized if the underlying finishes at or below the long put strike at expiration.

The spread benefits if price remains above the short strike or drifts upward. Time decay helps, since options lose extrinsic value as expiration approaches. If implied volatility falls, the value of the short put declines faster than that of the long put, improving the spread’s mark-to-market. A rules-based system might reduce exposure before expiration or based on a portion of the potential maximum gain, aligning implementation with the known payoff bounds.

Comparing the Two Examples

Both express a bullish tilt but with different emphases. The debit spread leans more on price movement, while the credit spread leans more on time decay and staying away from a price level. The debit spread limits cash outlay and requires less margin, while the credit spread brings in cash but uses margin equal to the potential loss. In a portfolio, combining both types across different underlyings and expirations can smooth sensitivity to volatility and time without implying any recommendation here.

Practical Design Choices

Strike Selection and Width

Strike width sets the economic stakes. Narrow spreads reduce both maximum profit and maximum loss, creating smaller dollar swings and often tighter bid-ask spreads. Wide spreads magnify both. Rules can standardize width or tie it to a measure of volatility so that payoffs scale with expected movement.

Days to Expiration

Shorter-dated verticals exhibit faster time decay and more pronounced gamma near the short strike. Longer-dated verticals carry higher extrinsic value and greater vega exposure, though still lower than single-leg options. A consistent expiration window simplifies comparisons and post-trade analysis.

Implied Volatility Context

Volatility regimes matter for risk but do not dictate a single correct choice. Debit spreads tend to be more forgiving when implied volatility rises after entry, while credit spreads tend to benefit when implied volatility falls. In systems, volatility context can be used as a filter for when to deploy or avoid certain structures, without referencing specific thresholds here.

Execution and Order Handling

Because execution quality materially affects realized performance, systems benefit from clear rules on order type and tolerance for slippage. Package orders often reduce legging risk. When liquidity is thin, pre-defined limits can prevent the system from participating rather than forcing low-quality fills.

Common Pitfalls

- Ignoring assignment mechanics: The long leg limits economic loss, but assignment can create temporary stock positions and additional commissions or interest. A written playbook for such events reduces surprises.

- Overconcentrating near a single strike: Clustering many spreads around the same strike compounds pin risk and correlation. Diversification across strikes and expirations reduces single-price-point exposure.

- Chasing ultracheap spreads: Very narrow debit spreads with tiny cost can have very low probability of reaching maximum value by expiration. Low cost does not equal low risk of loss in percentage terms.

- Underestimating slippage and fees: Theoretical edges can vanish after costs. Including conservative assumptions for slippage and commissions in testing and in live rules is prudent.

- Misinterpreting breakeven: Breakeven calculations are clean in theory but actual results depend on fill prices, assignment events, and closing costs. Systems should treat breakeven as a reference, not a guarantee.

Advanced Notes and Strategy Combinations

Verticals are building blocks for more complex structures.

- Butterflies and condors: Combining two verticals with shared middle strikes creates a defined-risk position that is more sensitive to time and less sensitive to direction.

- Put-call parity and synthetics: With the same expiration, a bull call spread is economically similar to a bull put spread under parity relationships, subject to dividends and rates. This equivalence allows systems to choose the more liquid side of the market without changing directional exposure.

- Dynamic hedging: Some traders overlay small underlying positions to fine-tune delta. This adds operational complexity and should be clearly codified if used.

- Rolling: Adjusting strikes or expirations can extend duration or modify risk. Rolls should follow objective criteria, such as time remaining or a fraction of maximum profit or loss, rather than discretionary judgment.

Testing and Validation in a Systematic Framework

Because vertical spreads constrain the range of outcomes, they are well suited to historical and forward testing. Robust validation avoids overfitting and respects the realities of execution.

- Out-of-sample testing: Rules for strike selection, expiration, and exits can be evaluated across different underlyings and time periods to test stability.

- Transaction cost modeling: Including realistic spreads and commissions is essential because verticals involve two legs per position. Conservative assumptions help prevent optimistic bias.

- Scenario analysis: Stressing volatility spikes, gaps in the underlying, and late-expiration pinning provides a better picture of tail behavior within the defined bounds.

- Portfolio aggregation: Performance should be assessed at the portfolio level, capturing correlation and overlapping exposures from multiple spreads.

Putting It All Together

Vertical spreads distill options trading into a manageable and programmable form. They offer a defined maximum loss and a defined maximum profit, a tempered sensitivity to volatility, and a directional bias that can be dialed up or down through strike selection. These characteristics make them an effective instrument for structured, repeatable trading systems that emphasize controlled risk and process discipline. When embedded within a complete framework that addresses liquidity, assignment mechanics, expiration management, and portfolio construction, vertical spreads can serve as a reliable unit of risk with predictable behavior across market conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Vertical spreads use two options of the same type and expiration but different strikes to create capped payoffs and defined risk.

- Debit spreads lean on price movement and generally benefit from rising implied volatility, while credit spreads lean on time decay and generally benefit from falling implied volatility.

- Maximum loss and maximum profit are known at entry, which supports consistent sizing and systematic exits.

- Greeks for verticals are moderated relative to single-leg options, reducing exposure to volatility shocks and extreme time decay.

- Operational rigor around liquidity, assignment, and expiration management is essential for reliable, repeatable results.