Options spreads convert directional or volatility views into defined payoff profiles that can be repeated as part of a rule-driven process. Two of the most widely used structures are credit spreads and debit spreads. Both use two options of the same type on the same underlying and expiration, but they collect or pay premium in different ways and express risk differently. Understanding their mechanics and the practical considerations around them makes it possible to build systematic playbooks that are consistent across market regimes.

Foundations: What a Vertical Spread Is

A vertical spread uses two options of the same expiration and the same type. One option is purchased and the other is sold at a different strike. The short and long legs offset a portion of each other’s price sensitivity, which defines the maximum profit and maximum loss at the outset. This defined structure is useful for risk control and for testing repeatable rules because the distribution of outcomes is constrained by construction.

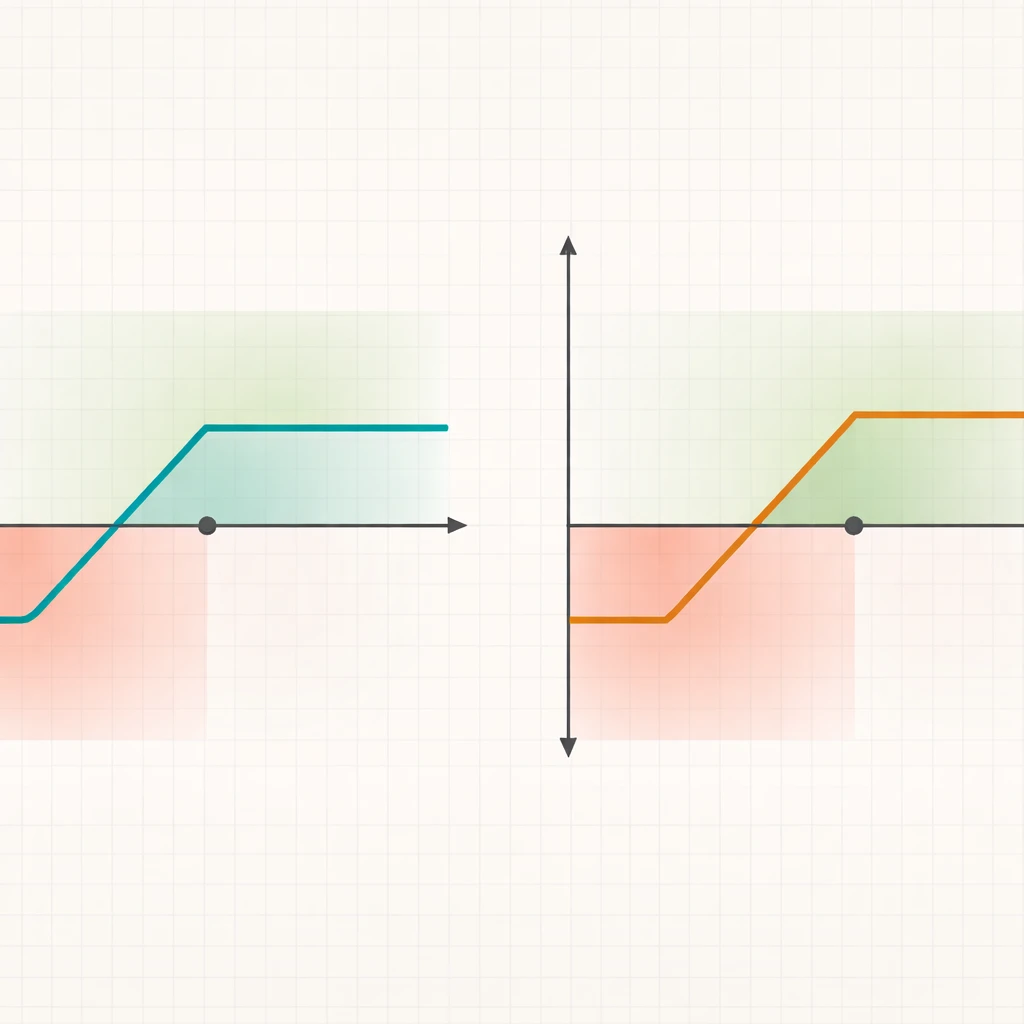

Two main variants exist:

- Credit spreads: Net premium is received upfront. Maximum profit is the net credit collected. Maximum loss is the strike width minus the credit, adjusted for contract multiplier.

- Debit spreads: Net premium is paid upfront. Maximum loss is the debit paid. Maximum profit is the strike width minus the debit, if the spread finishes fully in the money.

Both forms can be bullish or bearish. The bullish versions are the bull put credit spread and the bull call debit spread. The bearish versions are the bear call credit spread and the bear put debit spread.

Credit Spreads: Definition, Logic, and Mechanics

A credit spread is created by selling an option that is closer to the current price and buying a further out-of-the-money option for protection. The net effect is a cash inflow at initiation. The payoff is capped on the profit side by the credit received and capped on the loss side by the difference between the strikes minus that credit.

Example structures:

- Bull put credit spread: Sell a put at a higher strike and buy a put at a lower strike. Profits if the underlying stays at or above the short put strike at expiration, or generally if it does not fall significantly.

- Bear call credit spread: Sell a call at a lower strike and buy a call at a higher strike. Profits if the underlying stays at or below the short call strike at expiration, or generally if it does not rise significantly.

Core logic: The position benefits from time decay and from the underlying not moving beyond the short strike. Because the trader sells the nearer option and buys a further hedge, the spread typically has a positive theta. The position can also benefit when implied volatility contracts, since the short option dominates the position’s net vega in many cases.

Maximum loss and profit: If the spread width is W and the net credit is C, the maximum profit is C and the maximum loss is W minus C. The break-even price is the short strike adjusted by the credit, depending on whether the spread is a call or put.

Probability and payoff shape: Credit spreads often position the short strike outside the current price, which can create a higher estimated probability of expiring with profit. That higher probability is purchased at the cost of a lower payoff per winning trade and a larger loss on adverse outcomes. This trade-off is central to how credit spreads are used in systematic approaches.

Risk and operational considerations:

- Assignment risk can occur if the short option moves in the money before expiration, particularly around ex-dividend dates for calls on dividend-paying stocks. The long option provides a hedge but does not remove all operational complexity.

- Margin and buying power are set primarily by the defined width minus credit in many accounts. The structure is capital efficient because the risk is capped.

- Liquidity matters for both legs. Wide bid-ask spreads increase slippage and can distort realized edge in a system. Mid-pricing assumptions used in backtests should be stress-tested with realistic execution costs.

- Volatility regime influences results. Spreads initiated into elevated implied volatility may see beneficial contraction, while initiation into very low implied volatility can limit potential premium decay and may increase sensitivity to future volatility expansion.

Debit Spreads: Definition, Logic, and Mechanics

A debit spread is created by buying an option that is closer to the current price and selling a further out-of-the-money option to offset part of the cost. The net effect is a cash outflow at initiation. The payoff is capped on the profit side by the strike width minus the debit and capped on the loss side by the debit paid.

Example structures:

- Bull call debit spread: Buy a call at a lower strike and sell a call at a higher strike. Profits if the underlying rises sufficiently.

- Bear put debit spread: Buy a put at a higher strike and sell a put at a lower strike. Profits if the underlying falls sufficiently.

Core logic: The position pays for convexity and directional exposure while reducing cost by selling a further strike. Debit spreads typically have negative theta, since the net exposure is long the nearer option. They often have positive vega for long call spreads and bear put spreads, meaning rising implied volatility can help, although the short leg reduces the vega sensitivity relative to a single long option.

Maximum loss and profit: If the spread width is W and the debit is D, the maximum profit is W minus D and the maximum loss is D. The break-even is the long strike adjusted by the debit, depending on whether it is a call or put spread.

Probability and payoff shape: Debit spreads tend to have a lower probability of maximum profit because they require price movement toward the short strike and beyond to realize the capped upside. In exchange, the loss is limited to the debit and there is no assignment risk if both options are out of the money before expiration. If the long leg finishes in the money and the short leg does not, operational steps are required at expiration to avoid unwanted long or short stock positions.

Risk and operational considerations:

- Time sensitivity is material. Without sufficient favorable price movement, time decay erodes the debit. Clear rules for managing time-based decay are essential in systematic use.

- Volatility sensitivity can help or hurt. Rising implied volatility often increases spread value for long call or long put positions, though the short leg dampens the effect.

- Capital allocation is straightforward because maximum loss equals the debit. This can simplify position sizing in a rules-based portfolio.

Comparing Credit and Debit Spreads in a Systematic Framework

Although both are vertical spreads, their economic logic differs. Credit spreads monetize the passage of time and the tendency for prices to remain within a range. Debit spreads monetize directional movement while capping cost. A structured system can use either approach, or both, by defining when each style aligns with the system’s market state definitions and risk budget.

- Source of edge: Credit spreads emphasize theta and, in many cases, short volatility. Debit spreads emphasize directional delta with partial offsetting of cost through a short option.

- Payoff skew: Credit spreads typically realize smaller wins more frequently and occasional larger losses. Debit spreads often realize small losses more frequently and occasional larger wins.

- Greeks profile: Credit spreads often have positive theta and negative vega. Debit spreads often have negative theta and positive vega. Delta depends on strikes and can be tuned.

- Capital footprint: Credit spreads often consume margin equal to width minus credit. Debit spreads consume the debit paid. Both are capital efficient relative to naked options.

- Operational simplicity: Debit spreads may be simpler at initiation, while credit spreads can introduce assignment considerations. Both require attention at expiration.

Risk Management Considerations

Risk management is the primary reason to use spreads. Defined risk enables clear sizing, monitoring, and evaluation. Several practical dimensions deserve attention in a structured system.

- Position sizing: Determine the fraction of portfolio capital that a single spread can lose if it hits maximum loss. For credit spreads, this is the width minus credit. For debit spreads, this is the debit. The sizing process should reflect aggregate portfolio risk, not just the risk of each isolated position.

- Correlation and concentration: Multiple spreads across highly correlated underlyings can concentrate risk. A rules-based system can cap sector or factor exposure to prevent simultaneous adverse moves from overwhelming the portfolio.

- Volatility regime alignment: Define how initiation criteria vary with implied volatility percentiles. For credit spreads, high implied volatility often raises premium and can increase room to the short strike, but also coincides with larger price swings. For debit spreads, low implied volatility may reduce cost, but price movement becomes critical.

- Event risk: Earnings, economic releases, product announcements, and regulatory events can cause gaps. Rules can address whether to avoid initiation near scheduled events, reduce size, or adjust expirations. The choice should be consistent and tested.

- Liquidity and slippage: Target underlyings and expirations with reliably tight bid-ask spreads and sufficient open interest. Limit orders and staged execution rules can be incorporated into testing assumptions to better approximate live results.

- Assignment and exercise: Credit spreads carry early assignment risk on the short leg, especially for calls near ex-dividend dates or deep in-the-money options with little extrinsic value. Systems should specify how to respond to assignment, including using the long leg to close or hedge the resulting position.

- Expiration and width selection: Shorter-dated credit spreads concentrate theta and gamma risk into fewer days. Longer-dated debit spreads allow more time for a move but suffer more theta exposure in absolute terms. Width influences payoff symmetry and margin. The choices should be rule-based and justified by testing.

- Exit management: Closing early at preset profit or loss thresholds, using time-based exits, or adjusting positions by rolling are all operational choices. Each method changes the distribution of outcomes. They should be evaluated against the system’s objectives.

- Transaction costs: Two legs mean double the commissions and potentially more slippage. Test performance with conservative cost assumptions.

High-Level Numerical Examples

All numbers below are illustrative only. They are intended to clarify mechanics rather than suggest any action.

Credit Spread Example: Bull Put

Assume an underlying trades at 100. Consider a bull put credit spread that sells the 95 put and buys the 90 put in the same expiration. Suppose the net credit is 1.20 per share and the strikes are 5 points apart.

- Maximum profit: 1.20 per share, realized if the underlying finishes at or above 95 at expiration.

- Maximum loss: 5.00 minus 1.20 equals 3.80 per share, realized if the underlying finishes at or below 90 at expiration.

- Break-even: 95 minus 1.20 equals 93.80.

- Theta and vega: Typically positive theta and negative vega. Time passing without a large downward move helps. A drop in implied volatility usually helps as well.

Scenario intuition:

- If price finishes at 100, the spread expires worthless and the 1.20 credit is retained.

- If price finishes at 94, the 95 short put is 1 in the money, the 90 long put is out of the money. The spread is worth about 1, so profit is roughly 0.20 before costs, net of the initial credit.

- If price finishes at 88, the spread is maximally in the money with value of 5. Loss is 3.80 before costs.

This profile illustrates the higher probability of small profit versus the possibility of a comparatively larger loss. In a system, this profile is compatible with rules that define acceptable tail risk and consistent exit criteria.

Debit Spread Example: Bull Call

Assume the same underlying at 100. Consider a bull call debit spread that buys the 100 call and sells the 105 call in the same expiration. Suppose the net debit is 1.80 and the strikes are 5 points apart.

- Maximum profit: 5.00 minus 1.80 equals 3.20 per share, realized if the underlying finishes at or above 105 at expiration.

- Maximum loss: 1.80 per share, the debit paid.

- Break-even: 100 plus 1.80 equals 101.80.

- Theta and vega: Typically negative theta and positive vega. Time passing without an upward move erodes value. Rising implied volatility may help prior to expiration.

Scenario intuition:

- If price finishes at 108, the spread is worth 5, producing 3.20 profit before costs.

- If price finishes at 102, the 100 call is 2 in the money, the 105 call is out of the money. The spread might be worth about 2, implying a small gain of 0.20 before costs.

- If price finishes at 98, both options expire worthless and the loss equals 1.80.

This profile illustrates the need for directional movement and the convenience of a defined worst-case loss equal to the debit. In a system, this can fit a regime that expects momentum or breakouts with controlled cost.

How Credit and Debit Spreads Fit Structured, Repeatable Systems

Spreads are amenable to codified playbooks because their payoffs are known in advance and their sensitivities can be tuned with strike, width, and time to expiration. A structured system can determine when, how, and how much to deploy without discretionary overrides.

- Signal definition: Rules can reference trend filters, volatility percentiles, or price relative to moving averages, without prescribing specific entries. The objective is to map market states to the style of exposure the system seeks, whether time decay for credit spreads or directional convexity for debit spreads.

- Strike and width selection logic: Systems often index strikes to target deltas or probability bands to control distance to the short strike in credit spreads and to define expected move capture in debit spreads. Width sets the potential payoff and the risk. The rules must be internally consistent and testable.

- Time to expiration: Shorter maturities intensify theta and gamma dynamics, while longer maturities distribute outcomes over more days and increase vega exposure. A system can segment expirations by goal, such as quicker decay harvest for credit spreads or more time for directional follow-through in debit spreads.

- Entry and exit scheduling: Calendaring rules, such as avoiding openings during specific events or using time-based exits, reduce noise and standardize implementation. Exit logic can include partial profit thresholds, fixed holding periods, or rolling criteria that do not depend on prediction.

- Risk budgeting: Define per-trade risk caps and portfolio-level limits. Credit spreads consume margin based on width minus credit, while debit spreads consume cash equal to the debit. Aggregate limits help control adverse clustering during volatile regimes.

- Performance measurement: Evaluate expectancy, payoff ratio, hit rate, and drawdown characteristics, not just average profit. Credit and debit spreads produce different distributions of returns, so risk-adjusted metrics and scenario analysis are central.

- Execution and slippage modeling: Include realistic fill assumptions. Even small slippage on two legs can materially alter edge for high-frequency spread systems.

Greeks and Sensitivities in Practice

Greeks describe how spreads respond to underlying changes, time, and implied volatility. They help translate rules into expected behavior.

- Delta: Debit spreads concentrate delta in the long leg near the money, which decays as the position moves deeply in the money due to the short cap. Credit spreads typically carry smaller net delta at initiation when placed out of the money.

- Theta: Credit spreads generally collect time value each day, all else equal. Debit spreads generally pay time value each day. Theta is not constant and accelerates near expiration.

- Vega: Many credit spreads are net short vega, while many debit spreads are net long vega. Volatility changes can shift mark-to-market significantly before expiration, even if ultimate expiration payoff is defined.

- Gamma: Near expiration, gamma increases. Credit spreads become more sensitive to price moves near the short strike. Debit spreads can gain or lose value rapidly as they approach or cross the short strike.

Operational Nuances and Edge Preservation

Repeatable systems suffer when operational frictions are ignored. Small differences compound over many trades.

- Order routing and partial fills: Spreads can be routed as complex orders to improve execution quality. Partial fills can change risk temporarily if one leg executes without the other. Systems should specify handling rules for that scenario.

- Weekend and holiday effects: Time decay is not linear across days. Mark-to-market moves on Fridays and Mondays can be counterintuitive. Rules can avoid assumptions about daily decay and rely on tested behaviors instead.

- Expiration management: Automatic exercise and assignment rules vary by broker and exchange. The system should specify close-out timing to avoid unwanted stock positions or margin changes at expiration.

- Tax and accounting context: Record-keeping for multi-leg strategies is more involved. While this does not change payoff, it affects how results are measured and compared.

Common Pitfalls

Several mistakes undermine the integrity of spread strategies.

- Overestimating the probability of profit for credit spreads by using static deltas that do not account for volatility clustering and jumps.

- Ignoring that debit spreads can decay quickly if volatility falls or if the underlying stalls near the long strike.

- Using unrealistically tight execution assumptions in tests, which inflates edge.

- Allowing correlated exposures across symbols to exceed the intended risk budget.

- Failing to predefine responses to assignment, especially during corporate actions.

When Each Structure Tends to Align with System Goals

Neither credit nor debit spreads is superior in all conditions. The match depends on the system’s economic rationale and constraints.

- Income-like objectives: Systems that seek frequent, smaller gains with controlled tail risk often line up with credit spreads. The logic depends on disciplined size and clear tail protocols.

- Convexity-seeking objectives: Systems that seek to capture directional moves with limited upfront cost tend to align with debit spreads. The logic depends on credible movement signals and patience within defined holding periods.

- Hybrid approaches: Some systems allocate between credit and debit spreads based on volatility and trend filters. The key is internal consistency rather than tactical improvisation.

Extending Beyond Vertical Spreads

While this article focuses on verticals, the same reasoning applies to other defined-risk structures. Calendars and diagonals shift the risk into the time dimension. Iron condors and butterflies combine multiple verticals to shape a more complex payoff. The same principles of defined risk, sensitivity to time and volatility, and operational discipline apply.

Closing Perspective

Credit and debit spreads use the same building blocks to pursue different risk-return profiles. Each embeds a trade-off among probability, magnitude, and sensitivity to time and volatility. When implemented with clear rules and realistic assumptions, both can be components of a structured system that emphasizes defined risk, consistent execution, and measurable outcomes. The structure does not remove uncertainty, but it organizes it in ways that can be tested and monitored over time.

Key Takeaways

- Credit spreads collect premium and typically benefit from time decay, offering higher probability of smaller gains with defined tail risk.

- Debit spreads pay premium and seek directional movement, offering capped upside with a defined worst-case loss equal to the debit.

- Risk management hinges on position sizing, regime awareness, liquidity, and explicit assignment and expiration protocols.

- Greeks profiles differ meaningfully, with credit spreads often short vega and positive theta, and debit spreads often long vega and negative theta.

- Structured systems rely on consistent rules for strike selection, expirations, entries, and exits, along with conservative execution assumptions.