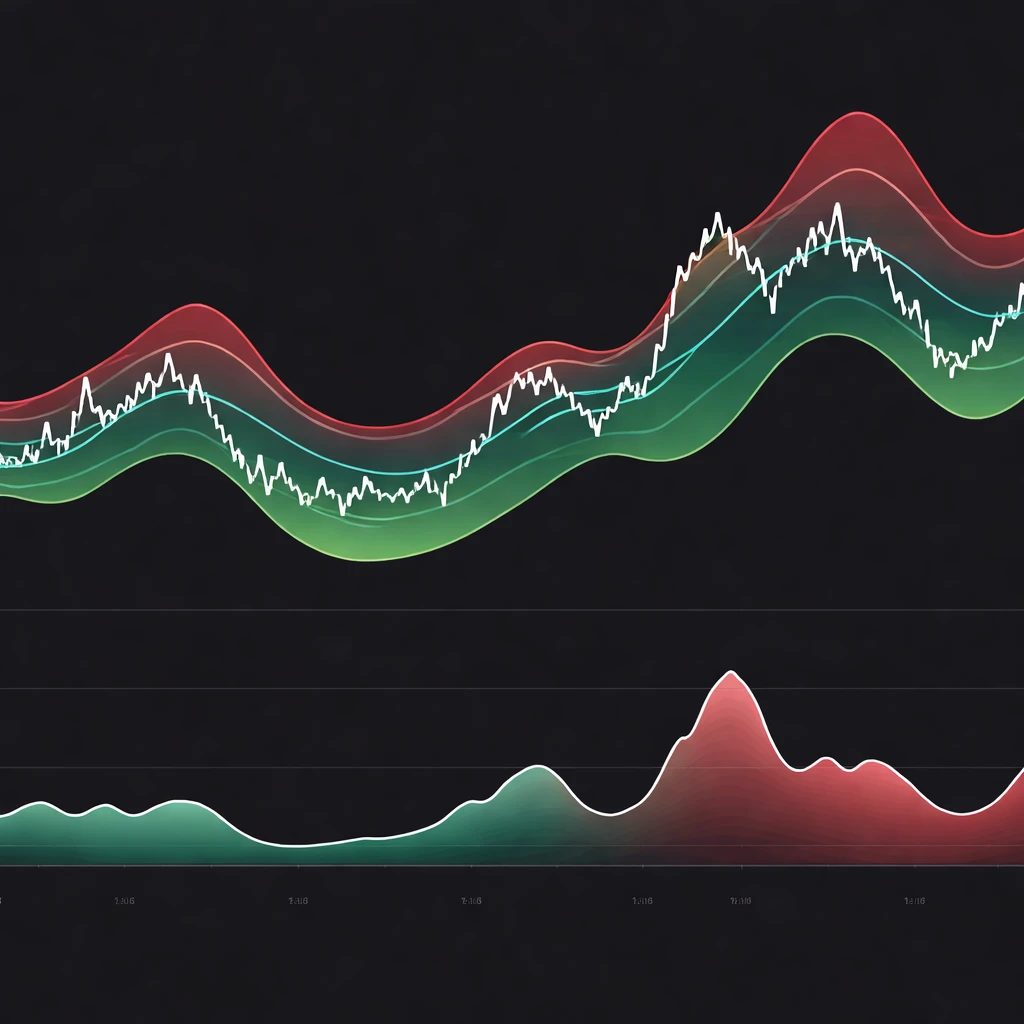

Mean reversion is a broad class of strategies that assume prices, spreads, or other market variables fluctuate around a changing reference level rather than drift unbounded. Volatility provides essential context for interpreting those fluctuations. Together, mean reversion and volatility form a foundation for systematic strategies that target small dislocations with disciplined sizing and explicit controls. The approach is not a prediction of future prices. It is a framework for defining what constitutes a “large” deviation relative to recent variability, then managing positions as that deviation changes.

Defining Mean Reversion and Volatility

Mean reversion refers to the tendency of a variable to move back toward a reference value after an excursion. In markets, the variable might be a price, a spread between two related instruments, or a market-neutral residual. The reference is often an estimate of a short or intermediate-term equilibrium, such as a moving average, exponentially weighted mean, rolling median, or model-implied fair value.

Volatility measures the dispersion of returns or price changes. It captures how widely and unpredictably the variable tends to move. Common estimators include the standard deviation of recent returns, exponentially weighted volatility, average true range, and parametric models such as GARCH. Volatility is dynamic and clusters in time. A deviation that appears large on a calm day may be trivial during a stormy period. Any mean reversion design that ignores volatility risks mistaking noise for signal or underestimating tail risk.

Core Logic of a Mean Reversion Strategy

At a high level, a mean reversion strategy operates by:

- Defining a reference level that represents the current “mean” or equilibrium.

- Measuring the current deviation of price or spread from that reference.

- Scaling that deviation by recent volatility to judge its statistical size.

- Allocating risk so that larger standardized deviations receive larger interest, subject to strict limits.

- Reducing or closing exposure as the deviation compresses or as risk constraints trigger.

The central idea is proportionality. A raw move of one unit means little without context. The same one-unit move during quiet conditions might be material, while during turbulent conditions it might be negligible. Normalizing by volatility keeps the framework stable across regimes.

Why Mean Reversion May Appear in Markets

Several mechanisms can produce reversionary behavior. Microstructure frictions can encourage short-horizon oscillations around liquidity pools. Inventory management by market makers can lead to price concessions that partially reverse as inventory clears. Behavioral features such as short-term overreaction, anchoring, or attention constraints can create transient mispricings. Constraints on capital and risk limits can force temporary dislocations that later compress.

None of these mechanisms guarantees consistent reversion. Markets undergo regime shifts, technology changes, and participant turnover. Mean reversion that appears robust in one period can attenuate or invert in another. A structured process therefore treats reversion as a hypothesis that requires continuous testing, not as a law.

Integrating Volatility Into the Design

Volatility informs three elements of a mean reversion system: signal definition, position sizing, and risk control.

- Signal definition: Deviations should be interpreted relative to recent volatility, often through a standardized score such as a z-score computed as (price minus mean) divided by a volatility estimate. Standardization aims for comparability across time and assets.

- Position sizing: Volatility targeting limits the contribution of any position to portfolio risk. When volatility rises, position sizes shrink for the same standardized deviation. When volatility falls, sizes increase, but usually within caps that prevent concentration.

- Risk control: Volatility changes can indicate regime shifts. Systems often tighten limits or pause when volatility accelerates beyond predefined thresholds, since reversion assumptions may be less reliable in stress states or trend-dominated tape.

Choosing a Reference Mean

The reference mean is not a fixed constant. It is an evolving estimate of fair value at the strategy’s horizon. Several choices exist:

- Simple or exponential moving averages: Useful for stationary or slowly drifting processes. Window length determines responsiveness. Short windows adapt quickly but can be noisy; longer windows are smoother but can lag.

- Rolling median: More robust to outliers, which helps in heavy-tailed data. The tradeoff is lower sensitivity.

- Model-based means: For spreads or residuals, a regression or state-space model can define the mean as a function of explanatory variables. Kalman filters allow the mean to evolve according to a latent process.

The choice should reflect the market’s half-life of deviations. If dislocations typically compress over hours, the reference must update fast enough to remain relevant. If deviations persist for days, a smoother, more stable mean can reduce whipsaw.

Estimating Volatility

Volatility estimation must capture clustering and fat tails while remaining tractable. Common approaches include:

- Rolling standard deviation of returns: Simple and transparent. Window length must balance responsiveness and noise.

- Exponentially weighted volatility: Places more weight on recent observations. This is useful when conditions change quickly.

- Average true range (ATR): Incorporates gaps and intraday range, useful for instruments where open-to-close misses relevant movement.

- Parametric models: GARCH-like models can reflect volatility persistence. They add complexity and parameter risk, but for some assets they improve stability.

- Robust estimators: Median absolute deviation or truncated variance can limit the influence of extreme outliers that would otherwise inflate risk estimates temporarily.

The estimator should match the strategy’s horizon. Intraday mean reversion often benefits from high-frequency realized volatility or short-horizon exponential estimates. Multi-day strategies may prefer smoother measures to reduce turnover caused by transient spikes.

Regime Sensitivity and When Reversion Fails

Mean reversion can disappear during momentum-dominated or news-driven regimes. Structural breaks, policy changes, and liquidity withdrawals can lead to prolonged trends that overwhelm a reversion hypothesis. Practical systems incorporate regime filters, for example, a volatility shock filter, a trend filter that limits exposure when the reference itself is drifting rapidly, or a market-state classifier trained on historical features.

Change-point detection tools can flag shifts in distribution. While no test is definitive, a combination of indicators such as rising serial correlation of returns, exploding cross-asset correlations, or a jump in realized volatility relative to forecast can justify temporary de-risking. The design intent is not to predict the regime, but to reduce exposure when conditions contradict the statistical structure that the strategy assumes.

Risk Management Considerations

Risk management is central to mean reversion with volatility, since adverse excursions can be correlated and sudden. Key themes include:

- Volatility targeting and position caps: Limit risk contribution per position and per asset class. Caps prevent a single asset from dominating the portfolio when volatility compresses.

- Drawdown limits and kill switches: Predefined thresholds halt trading or reduce exposure when losses exceed tolerances. This acknowledges that distributions can change faster than models adapt.

- Time risk and event risk: Deviation half-lives are uncertain. Exposures that do not compress within a reasonable time may represent regime shifts rather than signal. Scheduled events with jump risk can merit reduced exposures.

- Gap and tail risk: Reversion strategies often lean against price moves, which can be hazardous into gaps. Buffering through smaller sizing, diversification, and robust volatility estimates helps manage asymmetry.

- Transaction costs and slippage: Mean reversion trades can turn over frequently. The signal must clear an estimated cost hurdle that reflects liquidity, spread, adverse selection, and market impact.

- Correlation and concentration: Multiple assets may revert simultaneously for the same reason, which increases effective exposure. Portfolio-level risk measures should account for cross-asset dependence, not just individual limits.

From Idea to Structured, Repeatable System

A structured system formalizes each step from data to decision. Elements typically include:

- Data handling: Reliable, timestamped prices with confirmed corporate actions, session boundaries, and stale-quote filters for less liquid markets.

- Signal construction: Define the reference mean, compute deviations, normalize by volatility, and apply filters that reflect liquidity or regime conditions.

- Portfolio construction: Convert signals into target risk contributions subject to exposure caps, diversification rules, and estimated transaction costs.

- Execution: Choose order types and schedules that control slippage while avoiding excessive signaling of intent. Latency and queue position can matter for short-horizon strategies.

- Monitoring and governance: Real-time checks for data anomalies, limit breaches, and performance drifts, with clear protocols for pausing or resuming the system.

High-Level Example: Volatility-Normalized Reversion

Consider an equity index future that often overshoots an intraday equilibrium during volatile openings, then compresses toward that equilibrium as liquidity normalizes. A system could define a reference level using a short-horizon exponential average of mid-prices or a session-based benchmark such as a rolling volume-weighted measure. Deviations are standardized by an exponentially weighted volatility of short returns, which captures the current pace of price change.

When the standardized deviation becomes materially large relative to recent history, the system records a potential opportunity. Position sizing derives from a volatility target that allocates a fixed risk budget per standardized unit of deviation, subject to maximum leverage, instrument-specific caps, and limits near scheduled announcements. If the deviation compresses, exposures reduce proportionally. If volatility spikes or a time limit passes without compression, the system curtails risk to avoid anchoring to a moving reference.

No thresholds or entry rules are specified here. The point is the architecture. The signal is the normalized deviation, the sizing responds to volatility, and the exits are driven by both statistical compression and risk constraints. The same template can be adapted to other assets, horizons, or to cross-sectional mean reversion in which the reference is a sector or factor benchmark rather than the instrument’s own moving average.

Cross-Sectional Versus Time-Series Reversion

Mean reversion strategies often fall into two categories. Time-series reversion focuses on a single instrument reverting toward its own reference level. Cross-sectional reversion focuses on relative mispricings across a peer group. For example, within a sector, some constituents may drift above a factor-implied value while others lag. The strategy then targets the spread between winners and losers normalizing by idiosyncratic volatility and correlation. Cross-sectional approaches tend to be closer to market neutral if constructed with beta or sector constraints, which can reduce market direction risk. They also introduce correlation risk across names when the common factor moves strongly.

Pairs, Spreads, and Stationarity

Pairs or spread strategies are common mean reversion variants. The logic holds when a linear combination of two or more assets forms a process with a stable mean. Econometric tools such as cointegration tests help determine whether a spread has a tendency to revert. Even when tests support stationarity in-sample, a system still needs ongoing validation and re-estimation. Relationship breaks can arise from corporate events, index rebalances, or shifts in business fundamentals.

Mean Reversion in Volatility Itself

Volatility is not only a conditioner of signals. It often exhibits mean reversion in its own right. Realized volatility tends to cluster and then fade, while implied volatility reacts quickly to shocks and mean reverts more slowly. Strategies that trade volatility directly, for example with variance swaps or options, require specialized modeling of volatility surfaces, convexity, and carry. The conceptual lesson still applies. Standardize deviations, scale risk to the current level of variability, and recognize that regime changes can suspend reversion for extended periods.

Transaction Costs, Liquidity, and Capacity

Mean reversion can involve frequent rebalancing, especially on short horizons. Cost-aware design is crucial. Realistic models of bid-ask spreads, fees, market impact, and order-book depth determine whether a theoretical edge survives execution. Liquidity conditions can change within the day, across venues, and around news events. Capacity limits may be reached quickly in smaller instruments when multiple participants pursue similar ideas. A robust system estimates marginal slippage as size increases and applies self-limiting rules that prevent deterioration of realized performance.

Backtesting and Evaluation

Evaluation must guard against data leakage and overfitting. Distinct in-sample and out-of-sample periods help validate stability. Walk-forward testing, where parameters are recalibrated on a rolling basis and then tested on subsequent data, better reflects live adaptation. Bootstrap methods can quantify uncertainty in performance metrics by resampling returns with attention to serial dependence.

Metrics should reflect the character of mean reversion. Hit rate may be high while average win is small; conversely, a lower hit rate with larger mean reversion moves can work if tails are controlled. Autocorrelation of strategy returns, volatility of returns, and skewness provide insight into risk. Drawdown profiles help identify hidden concentration. Cost attribution distinguishes signal quality from execution quality. A large share of slippage can indicate that signals are too close to noise or that execution timing is revealing intent.

Model Stability and Parameter Discipline

Mean and volatility horizons determine what the system perceives as equilibrium and noise. Frequent parameter changes can inadvertently chase the latest sample. Stable parameterization, subject to periodic review, supports repeatability. Where adaptation is necessary, bounded learning rates and guardrails help. For example, volatility half-life can be updated within a set range rather than recalculated freely each day. This reduces the risk of sudden swings in sizing after an outlier day.

Handling Outliers and Jumps

Outliers challenge mean reversion systems because they can skew both the mean and volatility estimates, which then distort signals and sizing. Robust estimators, capping of standardized deviations, and jump filters help contain this effect. A system can also treat outlier days differently in risk budgeting, preventing the next session’s risk from being dominated by a single shock. Time-of-day patterns matter as well. Opening and closing auctions, index rebalances, and earnings windows can exhibit different noise-to-signal characteristics than the rest of the session.

Governance, Controls, and Documentation

A repeatable approach is explicit about governance. Data lineage, parameter sets, and change logs should be documented. Controls include unit tests for calculations, reconciliations of signals against raw data, and surveillance for stale inputs. Pre-trade and post-trade analytics confirm that actual exposures matched intended risk budgets and that realized costs align with expectations. These operational practices are part of the strategy’s edge, because they reduce unforced errors that otherwise compound quickly in high-turnover approaches.

Illustrative Walkthrough Without Signals

To make the interaction between mean reversion and volatility concrete, consider an illustrative workflow for a single instrument. The system computes a short-horizon exponential mean of mid-prices to represent the evolving equilibrium. It then estimates volatility using an exponentially weighted standard deviation of returns that updates each minute. The current deviation is the difference between price and the reference mean divided by this volatility estimate. If the deviation exceeds an internal relevance threshold, the model forms a provisional exposure scaled so that the product of position size and volatility approximates a constant risk contribution. Additional filters reduce exposure ahead of scheduled announcements or when estimated volatility jumps beyond a guardrail. The position reduces mechanically as the standardized deviation narrows or as a maximum holding time is reached, whichever comes first. At close, the system neutralizes exposures to avoid overnight gap risk if the design is intraday only.

This walkthrough avoids explicit trade instructions. Its purpose is to show the flow from observation to normalized signal, to risk-aware sizing, to rule-based de-risking, all mediated by volatility.

Common Pitfalls

Several pitfalls recur in mean reversion design:

- Ignoring structural change: A strategy that worked in one liquidity regime may underperform when the market microstructure changes.

- Over-sensitivity to parameters: If small tweaks to the mean or volatility windows flip performance, the edge is likely unstable.

- Cost blindness: Backtests that do not include realistic spreads, fees, and market impact tend to overstate edges in short-horizon reversion.

- Concentration through correlation: Signals that appear diversified across names may load on a single factor. Stress tests should consider shocks to that factor.

- Anchoring to an outdated reference: In trending markets, the true equilibrium can drift. Without safeguards, the system may accumulate exposure against a moving target.

Fitting Mean Reversion Into a Broader System

Mean reversion and volatility-aware sizing can complement other approaches. For example, trend filters can reduce exposure during periods when reversion is unreliable. Cross-asset overlays can limit portfolio-level drawdowns. Cash and collateral management matter when strategies involve derivatives. A broader system treats each component as a modular contributor to total risk, with clear interfaces for signals, limits, and execution.

Concluding Perspective

Mean reversion strategies gain discipline from explicit treatment of volatility. The combination transforms raw price moves into standardized signals, then converts those signals into controlled exposures that adapt to changing conditions. The discipline protects the strategy when conditions evolve, while the standardization supports comparability across assets and time. The result is a framework that can be tested, monitored, and refined as part of a structured, repeatable trading process.

Key Takeaways

- Mean reversion interprets price or spread deviations relative to an evolving reference mean and requires careful volatility normalization.

- Volatility shapes signal relevance, position sizing, and risk control, especially during regime shifts when reversion can weaken.

- Robust estimation of both the mean and volatility improves stability by limiting the influence of outliers and rapid structural change.

- Transaction costs, liquidity, and correlation are central constraints, since mean reversion often involves high turnover and clustered exposures.

- Structured systems emphasize governance, testing, and monitoring so that small statistical edges survive real-world execution and risk.