Mean reversion across timeframes is a structured way to exploit temporary dislocations in price while respecting the broader state of the market. The core idea is simple. Prices often wander around a reference level that changes with the horizon being observed. A short-term chart may show oscillations around a rapidly changing local average, while a weekly chart may reveal a slower and more persistent tendency. A multi-timeframe approach looks for alignment or tension between these horizons, then builds rules that systematically act on short-term deviations when higher-horizon conditions are supportive.

This article clarifies the concept, the rationale that underpins it, and how to incorporate it into a repeatable process. It also discusses risk management choices that are particularly relevant to reversion strategies and offers a high-level operational example. The discussion avoids trade instructions, price levels, and recommendations. The emphasis is on structure and understanding.

Defining Mean Reversion Across Timeframes

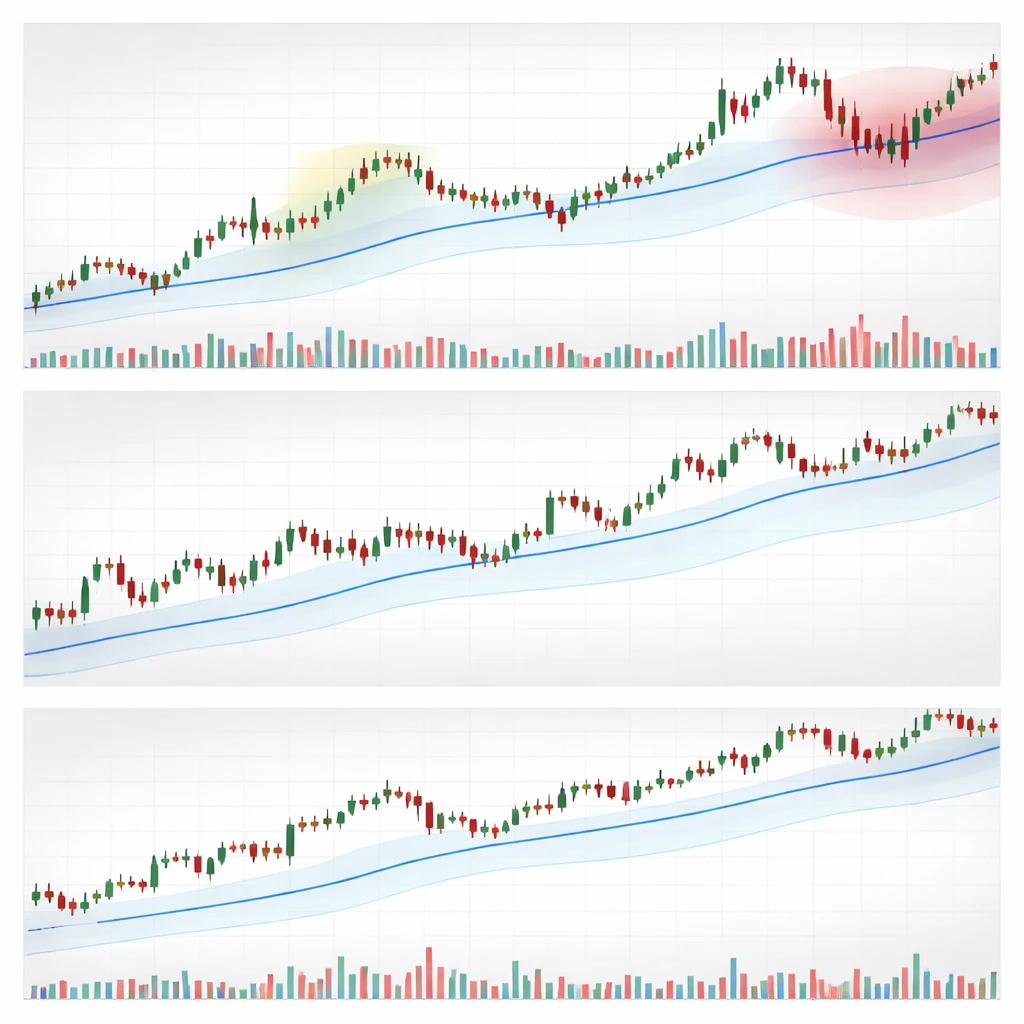

Mean reversion is the tendency for a variable to move back toward a central value after drifting away. In markets, this central value could be the average of recent prices, a volume-weighted average, or a statistically defined equilibrium such as the midline of a band constructed from historical volatility. Mean reversion across timeframes extends this idea by considering at least two horizons simultaneously. For instance, an intraday pullback toward a session mean can be interpreted differently depending on whether the daily or weekly trend is flat, rising, or falling.

At the heart of the approach are two linked questions. First, how do we define the mean on each horizon. Second, how do we use the relationship between short-horizon deviation and higher-horizon state to structure decisions. A pure single-horizon mean reversion model might consider only the distance from a short-term moving average. A multi-timeframe model adds a contextual filter, such as the slope or stability of a higher-horizon mean, the presence of a range-bound regime, or the absence of strong directional flows.

Why Timeframes Matter

Market behavior is not scale-invariant. Microstructure forces, liquidity provision, and order flow can drive reversion over minutes or hours, while macroeconomic narratives and valuation adjustments influence weeks and months. A method that ignores this layering may act against dominant forces. For example, a small dip inside a strong weekly uptrend can revert toward a short-term mean, but a deep intraday overshoot during a high-volatility news day may run far before mean forces regain control.

Multi-timeframe mean reversion uses the idea that mean reversion strength and speed depend on horizon. Three practical implications follow.

- The measured deviation should be normalized to the volatility of its own horizon. A two standard deviation move on a five-minute chart is not equivalent to the same label on a weekly chart.

- Reversion targets should match the horizon of the deviation. A short-term deviation often reverts toward an intraday mean, not necessarily to a weekly average.

- Filters based on higher-horizon state can help avoid reversion attempts that conflict with dominant flows. These filters do not eliminate risk, but they can shift the distribution of outcomes.

Core Logic of the Strategy Type

Mean reversion across timeframes typically involves three components. First, a definition of the mean for each relevant horizon. These can be moving averages, exponentially weighted averages that put more weight on recent observations, or volume-weighted references like VWAP. Second, a distance measure that expresses how far the current price is from the defined mean. Standardization is common. For instance, distance divided by recent volatility produces a z-like score that is comparable across assets and regimes. Third, a contextual filter derived from higher-horizon information. Examples include the slope of a daily mean, the percentile rank of daily volatility, or a range classification for the weekly chart.

These components can be combined into a repeatable template. Detect a short-horizon deviation that is sufficiently large relative to recent volatility. Check higher-horizon conditions for alignment with reversion, such as a flat or gently sloped mean, a contained volatility regime, or evidence of range behavior. If conditions pass the filter, a rule might authorize reversion attempts toward a predefined target like the intraday mean. If conditions fail, the system stands aside. The emphasis is on consistent treatment rather than discretionary judgment.

Defining the Mean and the Deviation

Defining the mean is not trivial. Different choices imply different behaviors.

- Simple moving average. Equal weight on each observation in a lookback window. Stable, slower to adapt.

- Exponential moving average. Greater weight on recent data. Faster to adapt, more reactive.

- Volume-weighted average. Incorporates traded volume and is widely used intraday to represent the session’s flow-weighted reference.

- Kernel or locally weighted estimates. Smooth estimates that can adapt to curvature in the data, though they require care to avoid overfitting.

Defining deviation requires a scale. Raw price distance can be misleading when volatility changes. Volatility-adjusted distances are more comparable. Common approaches use recent true range, rolling standard deviation, or robust measures like median absolute deviation. The goal is to express deviation in units of typical movement for that horizon, which improves portability across instruments and market states.

Higher-Horizon Context

The higher-horizon context can be thought of as a gatekeeper. When the higher timeframe indicates clear directional pressure, short-horizon deviations may persist longer before reverting. When the higher timeframe appears balanced, short-horizon deviations may revert more quickly and more frequently. Context can be captured via several proxies.

- Slope of the higher-horizon mean. Gentle slope suggests balance, steep slope suggests trend.

- Range classification. Distinguish range-bound from trend-like regimes using measures such as the ratio of net change to gross change over a window.

- Volatility regime. Elevated volatility can change the distribution of outcomes, particularly intraday.

None of these filters guarantees anything. They function as conditional weights in a playbook. They shift the probabilities but do not remove tail events where deviations grow larger before any reversion occurs.

Risk Management Considerations

Mean reversion strategies are exposed to specific risks that require explicit planning.

1. Trend day risk. A day or week with persistent one-way order flow can cause small reversion attempts to accumulate losses. Systems often include controls that limit the number of attempts per session, reduce size after a streak of failures, or impose time-based pauses when higher-horizon behavior becomes directional.

2. Volatility clustering. Volatility tends to cluster. A benign morning can turn disorderly after a catalyst. If position sizing does not scale with volatility, apparent edges can disappear into slippage and gaps.

3. Transaction costs and slippage. Mean reversion often implies shorter holding periods and higher turnover. The statistical edge must exceed realistic estimates of commissions, spreads, and impact. Backtests should stress cost assumptions and include scenarios with wider spreads.

4. Correlation and concentration. Reversion signals can fire simultaneously across correlated instruments, producing unintended concentration. Portfolio-level limits can help manage common-factor exposure.

5. Overnight and event risk. Reversion logic that spans sessions or days is sensitive to gaps around earnings, macro releases, and policy events. Calendars and regime flags can prevent exposure during known high-uncertainty windows.

6. Time stops and decay of information. The informational content of a short-horizon deviation decays quickly. Many practitioners use time-based exits if mean reversion does not materialize within a window aligned to the signal’s half-life.

7. Model drift and stationarity. The statistical properties of deviations can change. Continuous monitoring of hit rate, payoff ratio, and holding-time distribution is required to detect drift.

Estimating Reversion Speed

Although markets are not perfectly described by textbook processes, the intuition of a mean-reverting process like the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model is useful. The process has a parameter that governs how quickly deviations decay toward the mean. A practical way to think about it is the half-life of deviations. The half-life is the time it takes for a typical deviation to shrink by half under the model’s average dynamics. Estimating a half-life for different horizons provides a check on whether proposed holding periods are realistic for the intended timeframe. If a short-horizon signal historically decays within a small number of bars, holding it much longer may dilute the edge and increase exposure to regime changes.

In practice, half-life can be estimated from historical return regressions or by fitting a simple autoregressive model and converting its parameters to an equivalent decay rate. The point is not to insist that the process is exact, but to align holding periods and risk controls with observed reversion speed.

How the Strategy Operates at a High Level

The following examples illustrate mechanics without prescribing any specific signals or levels. They show how a multi-timeframe structure can be organized into a repeatable process.

Example 1: Intraday Reversion Conditioned on a Daily Filter

Consider an equity index future. The intraday engine monitors deviations from a session mean normalized by recent intraday volatility. A separate daily module classifies the higher-horizon state as balanced or directional by inspecting the slope and stability of a daily average. When the daily module indicates balance, the intraday engine is permitted to act on pronounced intraday deviations. When the daily module indicates a directional regime, the system either restricts reversion attempts or tightens risk controls. The intraday engine targets a return toward the intraday mean, and it uses a time stop aligned with the historical decay of similar deviations.

Example 2: Composite Multi-Horizon Deviation Score

In this structure, the system computes standardized deviations at several horizons, for example a very short window, an intermediate window, and a longer window. These standardized distances are combined into a composite score that reflects both the magnitude of the current short-horizon deviation and how atypical it is in the context of recent intermediate and long-horizon behavior. The composite score must exceed a threshold for the system to activate. The target is aligned to the horizon of the short deviation, while higher-horizon components act as a filter rather than a target.

Example 3: Range Classification as a Gate

A range classifier uses historical ratios such as net change over gross change to flag periods where price oscillates without sustained direction. During flagged periods, the system applies its reversion playbook more liberally. During trend-like periods, the system becomes conservative, reduces the number of attempts, or focuses on mean reversion only after very large deviations. The position sizing algorithm scales with realized volatility so that risk per attempt remains stable despite regimes changing.

Building Blocks for a Repeatable System

Mean reversion across timeframes benefits from a modular design. Each module can be validated independently and then combined.

- Feature definition. Choose the reference means for each horizon and the distance measures. Decide whether to use price, log price, or returns. Ensure the features are consistent across instruments.

- Normalization. Use volatility scaling or percentile ranks to make deviations comparable. Consider robust measures to reduce sensitivity to outliers.

- Context filters. Implement daily or weekly trend slope checks, range flags, and volatility regime tags. Calibrate them with out-of-sample data.

- Execution timing. Reversion edges can be time-of-day dependent in intraday systems. For example, openings and closes often behave differently from midday.

- Targets and time stops. Align targets with the generating horizon and set time stops based on observed decay characteristics.

- Cost model. Estimate spread, commission, and impact in backtests. Reversion with short holding periods is cost sensitive.

Backtesting and Evaluation

Empirical rigor is central to mean reversion research. Several practices are particularly relevant.

Out-of-sample validation. Reserve data for testing after development to reduce the risk of overfitting. Forward walk or anchored cross-validation can be useful in nonstationary data.

Cost and slippage realism. Use conservative cost assumptions and stress test scenarios with wider spreads or reduced liquidity. Consider queue position effects if limit orders are part of execution.

Holding period diagnostics. Examine the distribution of holding times. A strategy designed for fast reversion that often holds across multiple sessions is likely mismatched to its intended horizon or mis-specified.

Sensitivity analysis. Evaluate how results change when lookbacks and thresholds vary within reasonable ranges. A design that only works at one narrow parameter set is fragile.

Regime segmentation. Evaluate performance in trend-like versus range-like regimes, and across volatility states. This can reveal where the edge concentrates and where protective rules are most needed.

Dependency across instruments. If the system is applied to multiple assets, measure cross-correlation of signals and returns. Portfolio heat can rise quickly when many instruments revert simultaneously.

Operational Example Without Specific Signals

Imagine a futures portfolio that includes a liquid equity index contract. The operations team runs a daily routine to classify the coming session using higher-horizon data. If the weekly chart shows a flat or gently sloped mean and the daily volatility is within a historically normal band, the session is tagged as balanced. If the weekly mean is steep and daily volatility is elevated, the session is tagged as directional with high uncertainty.

During a balanced session, the intraday module monitors deviations from the session mean. When the deviation becomes statistically large relative to intraday volatility, the module prepares a reversion attempt. The potential target is the intraday mean, not the daily mean. Position size is set by a volatility budget designed to keep the expected loss from an adverse continuation within a fixed fraction of risk capital. A time stop is applied that corresponds to the typical decay window of such deviations. If the reversion unfolds quickly, the system may scale down exposure and reduce residual variance. If the reversion stalls, the time stop ends the attempt without waiting for the day to finish.

During a directional session, the system still observes deviations but the gate is stricter. Only unusually large deviations qualify, and the time stop is shorter to limit exposure to continuation. The playbook might also narrow its active hours to periods historically associated with microstructural mean reversion, such as midday consolidations, while avoiding the opening auction or late-session flows. The combination of stricter gates, smaller size, and shorter holding windows reduces participation when higher-horizon forces are likely to dominate.

Integrating Across Multiple Assets

Applying mean reversion across timeframes to multiple instruments introduces portfolio-level questions. Signal correlation can cause concentrated exposure if many assets deviate together. For instance, global equity indices often respond to the same macro cues, so simultaneous intraday deviations may trigger clustered activity. To manage this, limits can be placed on aggregate exposure to a sector or risk factor, and the system can allocate capital based on the relative extremity of each instrument’s standardized deviation. Capital can also be dynamically reallocated away from instruments that show declining reversion reliability.

Liquidity considerations are central. The fill quality of reversion attempts is sensitive to spread behavior during stress. Simulations should model the distribution of spread width and depth at the times when signals historically occur. Thin conditions can turn a theoretical edge into negative slippage.

Extensions and Variations

The multi-timeframe idea extends beyond absolute price reversion.

- Relative mean reversion. Look at the spread between two related instruments, such as a pair of sector ETFs or a futures calendar spread. Use higher-horizon context to decide when short-horizon spread deviations are more likely to mean revert.

- Options-based expression. Some desks express mean reversion views through market-neutral option structures while managing delta exposure intraday. The higher-horizon context still acts as a gate for deploying reversion risk.

- Anchored references. Anchored volume-weighted averages tied to significant events, such as monthly opens or major announcements, can serve as longer-horizon means against which short-horizon deviations are measured.

Governance and Process Discipline

Because mean reversion edges can be narrow and cost sensitive, governance matters. A documented playbook makes the process repeatable. It typically includes the feature definitions, filters, risk budgets, and exception rules. Monitoring dashboards track hit rate, average excursion before reversion, cost per trade, and the ratio of realized to modeled slippage. Post-session reviews check whether time stops aligned with decay estimates and whether the system respected its gates during directional conditions.

Change control is equally important. When the team considers adjusting a lookback or a volatility estimator, the change should be tested with out-of-sample data, then deployed gradually with position limits, and monitored for drift. A rule set that evolves slowly under governance is more likely to remain coherent than one that shifts frequently in response to short-term performance.

Common Pitfalls

Several recurring issues appear in mean reversion development.

- Confusing distance from mean with edge. A large deviation is not automatically an opportunity. Context and volatility matter.

- Ignoring fat tails. Tail events occur more often than a normal model implies. Controls for rare but large moves are essential.

- Overfitting thresholds. Designing rules that work only with a narrow z-score is fragile. Prefer ranges with robust performance.

- Underestimating costs. Backtests that omit partial fills, queue position, and changing spreads tend to overstate edge for short-horizon reversion.

- Timeframe mismatch. Targets and holding periods that do not match the signal’s decay characteristics lead to weak expectancy.

Where Mean Reversion Across Timeframes Fits

Within a broader framework of systematic strategies, multi-timeframe mean reversion fills a specific niche. It can provide diversification against momentum-oriented or breakout systems, since the return drivers differ. It also encourages disciplined participation only under conditions that historical analysis deems favorable. The approach leverages structure rather than prediction, and it relies on a workflow that can be audited and repeated across sessions and instruments.

Key Takeaways

- Mean reversion across timeframes combines short-horizon deviations with higher-horizon context to improve selectivity.

- Defining the mean, normalizing distance, and applying contextual gates form the core of a repeatable framework.

- Risk management focuses on trend day risk, volatility clustering, costs, correlation, and the decay of information.

- Backtesting must be cost aware, regime segmented, and validated out of sample to avoid fragile designs.

- Targets and holding periods should align with the estimated reversion speed of the horizon that generated the signal.