Introduction

Price action analysis focuses on the raw movement of price without reliance on derived indicators. Within this approach, a recurring event is the outside bar, a single bar whose range fully contains the prior bar’s range. Outside bars attract attention because they mark a period of range expansion and often reveal a shift in participation, sentiment, or liquidity. Understanding what they are, how they form, and how to interpret their context allows an observer to read charts in a structured, evidence-based way.

This article defines outside bars precisely, clarifies how they appear across chart types and timeframes, and explains why market participants monitor them. It also provides practical, chart-based examples that illustrate typical contexts in which outside bars occur. No trading strategies or recommendations are included.

Definition of an Outside Bar

An outside bar is a bar or candlestick whose high exceeds the prior bar’s high and whose low falls below the prior bar’s low. In other words, the entire price range of the current bar envelops, or engulfs, the previous bar’s range. The definition does not depend on where the bar opens or closes. The open and close affect the bar’s color and the shape of the candle body, but the outside classification relies only on the extremes of the high and low.

Many charting packages refer to this event as an engulfing bar or an outside day when applied to daily data. The core idea is the same: the current bar’s range expands enough to take out both the prior high and the prior low during the same bar. This is a range expansion event.

Anatomy and Properties

Consider two consecutive bars, A and B. Suppose bar A has a high of 102 and a low of 98. If bar B prints a high of 104 and a low of 96, then bar B is an outside bar relative to A because 104 is greater than 102 and 96 is less than 98. Whether bar B closes near its high, near its low, or near the middle does not change the classification as outside.

Three properties describe outside bars clearly:

- Range expansion: The distance between the high and low in the outside bar is larger than in the prior bar.

- Participation shift: Both the prior extremes are broken, which often implies a change in which participants are actively trading as price explores levels beyond the previous range.

- Context sensitivity: The information value of an outside bar is shaped by surrounding price structure, trend, volatility regime, and where the bar forms relative to recent support or resistance.

Outside Bars versus Related Terms

Several related terms appear in literature and platforms. They are similar but not identical:

- Engulfing candle: Often used interchangeably with outside bar, though some candlestick texts add color conditions such as body-to-body engulfing. Price action analysis typically focuses on range engulfing, not body engulfing.

- Outside day: A daily outside bar. The same definition applies on any timeframe; the label reflects the aggregation period.

- Key reversal: A more specific formation that usually includes an outside bar combined with a close that reverses the previous day’s direction. Outside bars do not require a particular close.

- Inside bar: The opposite case where the current bar’s high is lower than the prior high and the current low is higher than the prior low. Inside bars signal local range contraction, while outside bars signal expansion.

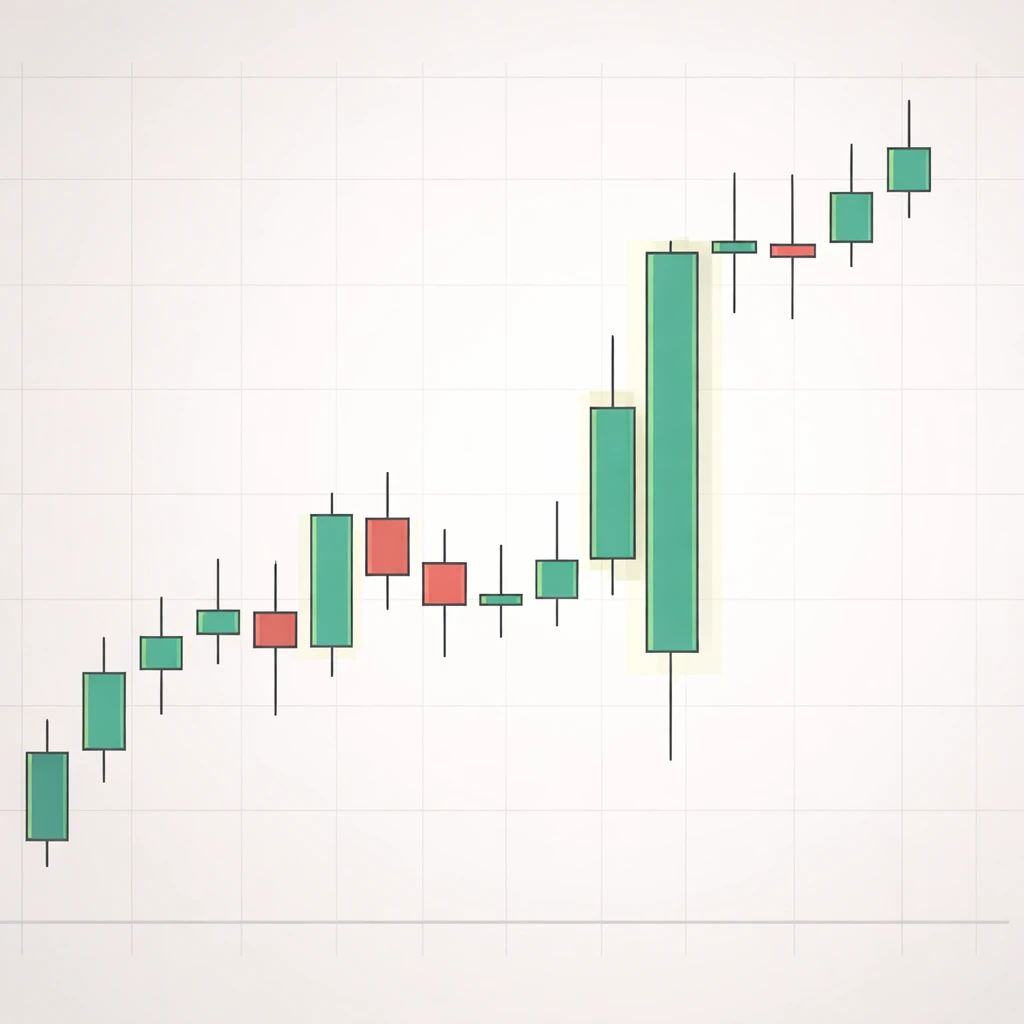

How Outside Bars Appear on Charts

Outside bars are visible on both OHLC bar charts and candlestick charts. On an OHLC bar chart, the outside bar simply has a taller vertical line than the prior bar, with its top above the prior high and its bottom below the prior low. On a candlestick chart, the candle wick penetrates both the prior high and prior low, and the candle body may be bullish or bearish depending on the relationship of open and close.

The appearance can vary depending on whether the move beyond the prior high or low occurs first. On intraday charts, price may initially drop to take out the prior low, then rally to surpass the prior high, or the sequence can be reversed. The visual result is a bar with long wicks on one or both sides and a broader total range than the previous bar.

Timeframe Dependence

Outside bars can occur on any timeframe, including minutes, hours, days, or weeks. Their frequency typically increases as the timeframe gets shorter because more bars are created and more noise is captured. On higher timeframes, outside bars are less common and can signal more significant shifts in participation simply because more trading activity is aggregated into each bar.

It is important to consider session boundaries when evaluating outside bars. For equities, overnight gaps can create outside days at the open if pre-market or opening prints immediately exceed the prior day’s high and low. In futures or currencies that trade nearly around the clock, session definitions and roll adjustments can alter how often outside bars appear and how they line up with perceived support and resistance.

Color and Body Shape

The color of a candlestick reflects the relationship between open and close and is not part of the outside definition. A bullish-colored outside bar that closes near the high communicates a different internal path of trades than a bearish-colored outside bar that closes near the low. Both are outside bars, but the close location can hint at which side exerted more influence by the end of the bar.

Some analysts compute a close location value within the range, often defined as the normalized distance of the close from the low, which runs from zero at the low to one at the high. Pairing the outside classification with the close location value provides more texture to interpretation without adding strategy rules.

Why Market Participants Watch Outside Bars

Outside bars matter because they represent range expansion and attempts to discover price beyond recently accepted levels. A market that extends both sides of the previous bar’s range has disturbed the balance of resting orders that previously contained price. That disturbance can be informative about volatility, liquidity, and the mix of buyers and sellers.

Range Expansion and Volatility Regimes

Markets alternate between periods of contraction and expansion. An outside bar is a concrete instance of expansion. If we measure volatility using the true range or average true range, outside bars generally push those measures upward. They can mark transitions between low volatility and higher volatility regimes, or they can occur as isolated events within already volatile conditions.

Because volatility influences position sizing, hedging practices, and risk controls for many participants, a sudden outside bar can prompt recalibration of behavior. That change in behavior, in turn, can affect subsequent price paths. The point is not that outside bars predict future movement, but that they identify a moment when conditions change in a measurable way.

Liquidity, Stops, and Order Flow Context

Taking out both the prior high and low often interacts with stop orders placed around recent extremes. When both sides are triggered in the same bar, the market has consumed liquidity above and below. This process can thin the order book temporarily or attract new liquidity providers, depending on the venue and asset. Observers monitor outside bars to infer when a market has performed a sweep of resting orders and when it has tested areas where supply or demand was previously detected.

Information Content and Ambiguity

Outside bars do not carry a single directional message. The same formation can occur in trending, range-bound, or volatile reversing conditions. Their information value comes from context: trend direction, proximity to support or resistance, higher-timeframe structure, and the location of the close within the bar. Treat an outside bar as a high-information event that requires reading of surrounding evidence rather than as a standalone signal.

Practical Chart-Based Examples

Example 1: Daily Outside Bar After Narrow Ranges

Suppose a stock has printed three consecutive relatively narrow daily bars, with true ranges around 1.2 percent of price. On the fourth day, an earnings-related news release increases participation. The day trades down early, breaking the prior day’s low by 0.3 percent, which triggers stops and invites short-term sellers. Later in the session, buyers emerge aggressively and the price rallies through the prior day’s high by 0.5 percent. The resulting daily bar has a range of 2.8 percent, substantially larger than recent bars, and it closes in the upper quartile of its range.

On a candlestick chart, this prints as a wide-range candle with wicks on both sides and a close near the top. It qualifies as an outside day because the high exceeded the previous high and the low fell below the previous low. Whether the next day follows through upward or retraces is not implied by the outside bar alone. The key point is that participation expanded, volatility lifted, and the market explored beyond a prior equilibrium.

Example 2: Intraday Outside Bar Around a Midday Breakout Attempt

Consider a 15-minute chart of a technology index future during a session that starts with a modest gap up. After an hour of sideways trading, price attempts a breakout above a morning range. The breakout draws in momentum buyers, but liquidity above the range is thin and larger sellers take advantage. Price reverses sharply, cuts through the morning range, and prints below the session low, triggering stops. It then rebounds into the prior range. The 15-minute bar that spans this episode takes out the prior bar’s high and low and closes near the midpoint.

Visually, this is a long 15-minute bar with long upper and lower wicks relative to the body. The bar communicates that both breakout buyers and range sellers were pressured within a short window. For observers, the event signals a local rebalancing of order flow and a jump in volatility.

Example 3: Numerical Illustration

Assume bar A has open 100.0, high 102.0, low 98.0, close 100.5. The next bar B has open 99.8, trades down to 97.9, rallies to 102.5, and closes at 101.8. Because 102.5 is greater than 102.0 and 97.9 is less than 98.0, bar B is an outside bar with a range of 4.6 points. The close likely colors the candle green on many platforms, but the classification does not depend on that. The meaningful feature is the enlargement of the range and the traversal of both sides of the prior bar’s extremes.

Context Matters: Reading Outside Bars in Structure

Outside bars are context-sensitive. Their interpretation depends on what preceded them and where they occur relative to visible reference points such as recent swing highs and lows or areas with heavy volume.

Within Trends

In a well-established uptrend characterized by higher highs and higher lows, outside bars can appear during pullbacks, consolidations, or impulse legs. An outside bar that aligns with the direction of the trend and closes near the extreme may be associated with acceleration within the trend, while an outside bar against the trend can mark a forceful counter-move. Neither case guarantees continuation or reversal, but both indicate active testing of opposing sides of the market. Reading these bars involves comparing them to recent bars: is the outside bar large relative to the past ten bars, or is it typical for the current volatility regime?

At Support or Resistance

When price approaches a well-observed support or resistance zone, outside bars often reflect a struggle to establish acceptance beyond that zone. For instance, if price has tested a resistance level several times without acceptance, an outside bar that probes above and below nearby ranges can be interpreted as an aggressive search for liquidity. Whether this search results in acceptance above the level or rejection back below it is an empirical question that requires observing subsequent price action rather than assuming a particular outcome.

During Consolidations

Sideways consolidations compress volatility as participants wait for new information. Outside bars within consolidations can be messy, created by rapid reversals that sweep local extremes and then mean-revert. They can also mark the beginning of an expansion phase that resolves the consolidation. Distinguishing between noise and meaningful expansion relies on the size of the bar relative to the consolidation width, where the close occurs within the bar, and the immediate follow-on behavior.

Higher-Timeframe and Lower-Timeframe Interaction

Every outside bar on a higher timeframe is composed of intricate swings on lower timeframes. A daily outside bar may embed several intraday attempts to trend in opposite directions. Conversely, clusters of intraday outside bars may build energy that finally expresses as a higher-timeframe range expansion. Viewing multiple timeframes helps reconcile these perspectives without trying to infer exact cause and effect.

Measurement and Cataloging

Formalizing the definition of an outside bar improves consistency. A strict rule uses strict inequalities: current high greater than prior high and current low less than prior low. Some charting data rounds prices, which can complicate equality cases. For consistency, many analysts require strictly greater than and strictly less than, not greater than or equal to. Equality at either extreme does not constitute engulfment under a strict rule.

To avoid labeling marginal cases as meaningful, some add a minimum range requirement relative to the prior bar or to a volatility measure such as the average true range. For example, a practitioner might record an outside bar only if its range exceeds 1.2 times the prior bar’s range or exceeds a fraction of current ATR. Such filters are analytical choices, not part of the basic definition.

Once criteria are set, one can catalog outside bars by frequency, average subsequent range over various horizons, and distribution of closes within the bar. These descriptive statistics do not prescribe trades. They simply characterize how often outside bars occur and what typical volatility patterns surround them in a given market and timeframe.

Reading Close Location Within the Outside Bar

The location of the close within the outside bar provides additional nuance. A close near the high might suggest that buying interest dominated by the end of the bar. A close near the low might suggest the opposite. A close near the middle may reflect balance after an exploratory move. Close location interacts with context. A close near the high inside an overall downtrend can indicate a forceful counter-move but not necessarily a change of trend. Likewise, a close near the low within an uptrend can reflect a sharp but temporary reaction. The focus is on how the close fits into the broader structure, not on assigning a single deterministic meaning.

Gaps, Data, and Market Microstructure Considerations

Gaps complicate outside bar identification, especially on daily charts of equities. If a stock gaps below the prior low at the open and later rallies above the prior high, the day prints as an outside day. Pre-market trading and auction dynamics impact whether such a move reflects genuine participation across the session or transient illiquidity at the open. Understanding the venue’s opening procedure, auction imbalance handling, and circuit breakers improves interpretation.

Data quality matters. Adjustments for splits and dividends can alter historical highs and lows. Tick-size constraints and rounding can produce misleading equality at extremes. Holiday sessions and half-days may distort the frequency of outside bars. When building rules to detect outside bars, it is prudent to standardize data, define session windows, and account for roll adjustments in futures.

Outside Bars and Volatility Clustering

Volatility tends to cluster. An outside bar often appears near transitions between quiet and active regimes or during an already active regime. Observers sometimes track sequences such as inside bars followed by an outside bar. The sequence highlights contraction followed by expansion, which is a basic rhythm of market behavior. Whether such sequences have any edge is an empirical question that requires testing and careful interpretation of sample size and market conditions.

Common Misreadings and Pitfalls

There are several ways outside bars can be misread:

- Overinterpreting single bars: A single outside bar in isolation rarely carries decisive directional information. Context matters more than the bar itself.

- Ignoring volatility regime: An outside bar in a high-volatility environment might be routine. The same bar size in a low-volatility regime could be notable.

- Confusing body engulfing with range engulfing: Some platforms highlight body-engulfing candles. These are not equivalent to true outside bars based on high and low.

- Data artifacts: Bad ticks or unadjusted corporate actions can create false outside bars that are later corrected.

- Session boundary issues: Comparing a 24-hour futures bar with a regular-hours equity bar can produce invalid conclusions about frequency and significance.

Using Outside Bars to Structure Observation

Outside bars are useful anchors for structured chart review. One can annotate charts to mark each outside bar, record its size relative to recent ranges, note where it occurred in relation to support or resistance, and log the close location value. These annotations provide a disciplined way to study how markets behave during range expansion events. They help separate the bar’s properties from narrative assumptions about what should happen next.

For instance, after marking an outside bar, one might examine the subsequent one to three bars for evidence of acceptance in the direction of the close, failure to hold extremes, or reversion toward the bar’s midpoint. Such observation helps build familiarity with how a specific market responds to range expansion. No single observation implies a plan of action. The goal is to understand behavior and variability.

Comparing Outside Bars Across Markets

Markets differ in volatility profiles, liquidity, and microstructure, which affects how outside bars appear. In large-cap equities with deep liquidity, outside days may be less frequent and often coincide with news catalysts or macro events. In small-cap equities or thinly traded futures contracts, outside bars can be more common and sometimes occur due to transient illiquidity. In currencies, where trading is nearly continuous, outside bars can reflect overlapping session flows, such as transitions between European and U.S. sessions.

Comparisons should account for these differences. A raw count of outside bars is less informative than a normalized measure, such as the percentage of bars that are outside relative to a rolling volatility baseline. Such normalization makes cross-market observations more meaningful.

Educational Summary of Interpretive Elements

Outside bars represent range expansion that traverses both prior extremes. They often coincide with tests of liquidity and shifts in participation. Their message is incomplete without context. Analysts frequently consider trend, proximity to key reference levels, volatility regime, and the close location within the bar to construct a balanced interpretation. Cataloging and measuring outside bars can add discipline to chart study by focusing attention on objective events rather than conjecture.

Key Takeaways

- An outside bar occurs when the current bar’s high exceeds the prior high and its low falls below the prior low, regardless of open or close.

- Outside bars are range expansion events that often reflect shifts in participation, liquidity tests, and changes in volatility.

- The interpretive value of an outside bar depends on context, including trend, nearby support or resistance, and the location of the close within the bar.

- Gaps, data quality, and session definitions can affect identification and significance, especially on daily charts.

- Outside bars are most useful as structured observation points for understanding market behavior, not as standalone predictive signals.