Definition and Core Purpose

A stop loss is a predefined instruction to exit a position once the market price reaches a specific level that indicates the original trade thesis is no longer valid. It converts uncertainty into a bounded loss by specifying an exit before emotions or noise can interfere. Whether implemented through an order placed with a broker or as a rule that is executed manually, a stop loss is an unambiguous decision threshold that controls downside risk.

Two ideas sit at the center of the concept. First, losses are inevitable in any probabilistic process, so the size of the average loss must be controlled. Second, survivability requires avoiding large drawdowns that are difficult to recover from. A stop loss is not a promise of the exact exit price, but it is a clear mechanism for limiting adverse excursions most of the time and for shaping the loss distribution when outcomes are unfavorable.

Why Stop Losses Matter for Risk Control and Survivability

Risk control has both mathematical and behavioral dimensions. Mathematically, a portfolio’s long-run path depends on the distribution of gains and losses. Even profitable strategies can fail if a small number of outsized losses erase prior gains. A stop loss constrains that tail by defining the maximum planned loss per position under typical conditions. Behaviorally, predefined exits reduce the temptation to rationalize holding a losing position in the hope that it recovers.

Survivability is about staying in the game long enough for an edge, if present, to express itself. If losses are capped and position sizes are aligned with those caps, drawdowns remain within tolerable bounds. The cumulative effect is a smoother equity curve, lower volatility of returns, and a reduced probability of ruin. None of this requires predicting the market. It only requires consistency in defining what invalidation looks like and exiting when that threshold is reached.

How Stop Loss Orders Work

In practice, stop losses can be implemented as firm orders or as rule-based manual actions.

- Stop market order: When the trigger price is touched, a market order is sent. The fill is prioritized but may occur at a price inferior to the trigger due to slippage.

- Stop limit order: When the trigger is touched, a limit order is placed at a specified limit price. This protects against extreme slippage but introduces non-execution risk if the market gaps past the limit.

- Trailing stop: The trigger dynamically follows the position as it becomes profitable, according to a fixed increment or a volatility measure. The trailing distance does not widen when price retraces.

- Mental or discretionary stop: The trigger exists in a plan or journal, and the exit is executed manually when reached. This avoids showing the order in the book but exposes the trader to hesitation and execution delays.

Execution mechanics vary by venue. In exchange-traded equities, a stop market typically converts to a market order once the stop price is touched. In futures, order handling is similar but occurs within the futures exchange environment and trading hours. Spot FX and many crypto venues are continuous, so stops may trigger at any time unless disabled. In all markets, thin liquidity, wide spreads, or trading halts can affect the quality and timing of the fill.

Forms of Stop Losses

There is no single correct form. The appropriate form depends on how one defines invalidation and on the characteristics of the instrument.

- Price-based stop: A fixed price level at which the original rationale is considered invalid. It might be below a recent swing for a long position or above a recent swing for a short position. The focus is on structural invalidation rather than arbitrary distance.

- Volatility-adjusted stop: A distance that scales with recent volatility using measures such as average true range. The goal is to avoid exits caused by normal noise without allowing unbounded risk.

- Time-based stop: Exit if the position fails to progress within a specified time window. This recognizes opportunity cost and the informational value of non-movement.

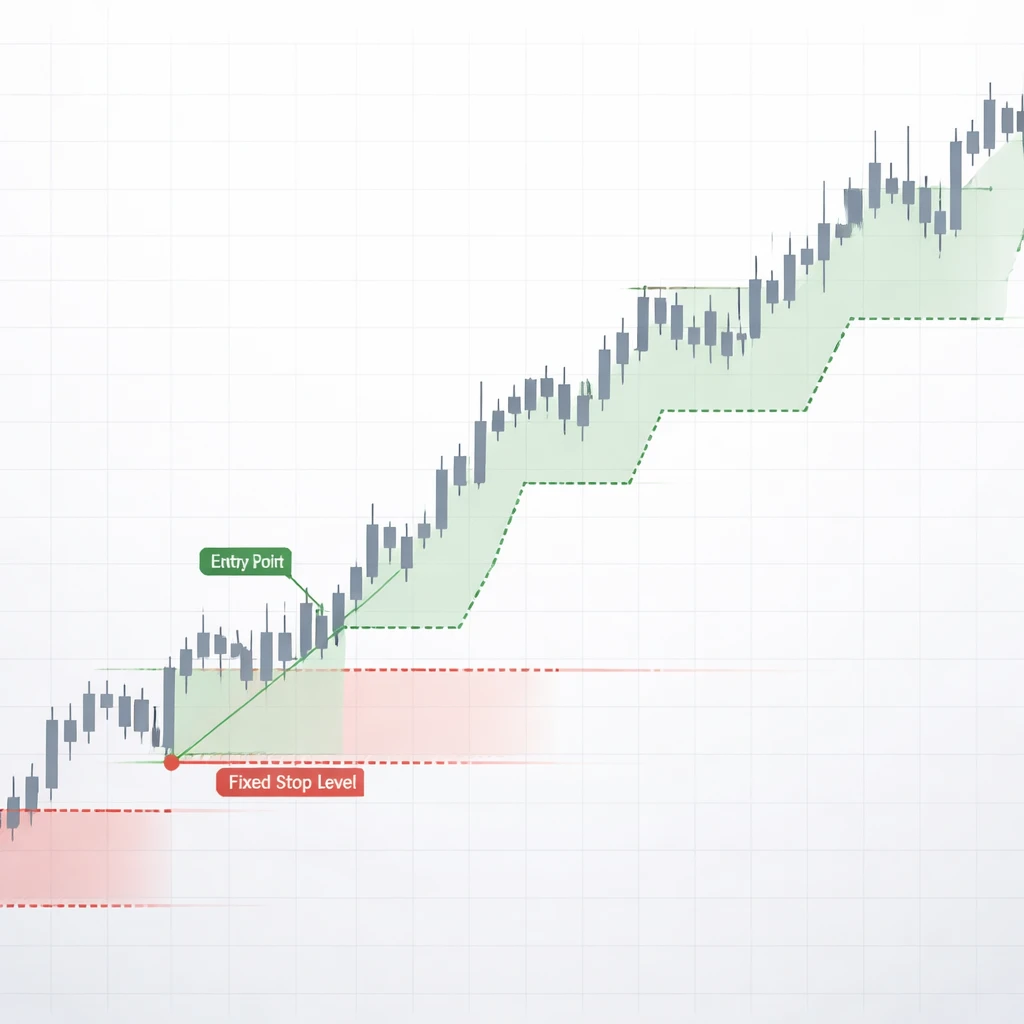

- Trailing stop: A stop that ratchets in the direction of favorable movement to lock in gains while allowing some room for fluctuation. The trailing logic can be fixed or volatility-sensitive.

- Event or condition-based stop: Exit when a defined non-price condition occurs, for example a scheduled announcement completed with an unexpected outcome, a change in liquidity regime, or a structural break in correlations. This requires clear rules to avoid subjective overrides.

Placement Logic Without Strategy Recommendations

Effective placement aligns the stop with the point at which the thesis is objectively broken, not merely uncomfortable. Stops that are too tight relative to the instrument’s typical noise profile lead to frequent, small losses that may accumulate. Stops that are too wide can reduce the number of trades closed prematurely but increase the size of each loss and may force small position sizes to maintain a constant risk budget.

Market microstructure matters. Instruments with wider bid-ask spreads, discrete tick sizes, or irregular liquidity may require more clearance to avoid accidental triggers from transient price spikes. Round numbers, previous highs or lows, and visible liquidity pockets can attract short-term flows. If a stop is placed exactly at widely watched levels, the probability of a touch may increase. None of this implies that such levels should be avoided categorically, only that placement should reflect an understanding of how orders interact with price formation.

Managing Stops After Entry

Stop management is a life cycle process: before the trade, during the trade, and after exit for review.

Before entry: The stop level and the position size can be planned together. The distance to the stop helps determine the maximum position size that keeps the dollar risk within a predefined budget. The plan should define when and how the stop can be moved, if at all.

During the trade: Adjustments can be made according to pre-specified rules. Moving the stop to break-even reduces downside but can also increase the chance of being exited during normal retracements. Trailing the stop as price advances can capture gains at the cost of potentially exiting before a larger move completes. Partial exits can be combined with stop adjustments to reduce exposure while allowing some participation.

After exit: The outcome and the path to it can be reviewed. Did the stop reflect true invalidation or was it hit by routine volatility? Were adjustments consistent with the plan? This post-trade analysis refines future placement and management without changing rules mid-trade.

Slippage, Gaps, and Execution Risk

Three execution risks affect how stops perform in the real world: slippage, gaps, and order handling under stress.

- Slippage: The difference between the expected exit price and the actual fill. Slippage tends to increase with volatility, speed of the move, and lack of liquidity. Stop market orders prioritize getting out, accepting slippage as the cost of immediacy.

- Gaps: When prices jump across levels between trades or across sessions, a stop can be triggered far from the intended level. Overnight news in equities or weekend news in some crypto markets can produce gaps. Stops still serve their function by getting the position out, but the realized loss can exceed the planned amount.

- Order handling under stress: In fast markets or during halts, stop orders may queue or convert at unfavorable prices. A stop limit can avoid extreme slippage but risks no fill if the market trades through the limit. The choice between stop market and stop limit is a trade-off between certainty of exit and price control.

Because a stop is not a guarantee of the exact exit price, a sensible risk plan acknowledges that actual losses can exceed the nominal stop distance. This is not a flaw of the concept but a reflection of how markets clear orders.

Stop Losses and Position Sizing

Stop placement and position sizing are inseparable. The distance between entry and stop determines the per-unit risk. Position size then scales that unit risk to a dollar amount consistent with the overall plan. If the stop is placed farther away to reduce the chance of a premature exit, the position size typically decreases to keep the dollar risk constant. If the stop is closer, the position size can increase for the same risk budget, but the probability of a stop-out may rise.

A useful way to analyze outcomes is to use R-multiples. Define 1R as the initial risk per trade, equal to the distance from entry to stop times position size. A loss that hits the stop is approximately minus 1R before slippage. A gain can be expressed as a positive multiple of R. Over many trades, the distribution of R results reveals whether the combination of entries, stops, and exits yields a positive expectancy while keeping drawdowns within tolerable limits.

Drawdown dynamics are asymmetrical. A 50 percent drawdown requires a 100 percent gain to recover. Limiting the size and frequency of large losses helps keep the capital curve within a recoverable range. Stops, combined with disciplined sizing, are the operational tools for enforcing that limit.

The Psychological Role of Stops

Markets confront participants with uncertainty and rapid feedback. Without predefined exits, decisions can become reactive. A clear stop reduces decision fatigue by turning many small choices into one planned action point. It also counters loss aversion, the tendency to hold losers longer than winners. By removing the option to negotiate with oneself when price approaches the threshold, stops reduce the odds of a single position growing into a portfolio problem.

At the same time, the presence of a stop does not eliminate discretion entirely. Traders still choose where to place it, whether to trail it, and whether to add or reduce exposure before it is hit. The discipline is in following the plan consistently, not in never making adjustments. Consistency enables learning because it creates comparable data.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

- Stops guarantee the exit price: They do not. They are triggers that submit orders under market conditions that may include gaps and slippage.

- Tighter stops are always better: Very tight stops can reduce loss size but increase the frequency of exits due to normal noise. Expected performance depends on the interplay between win rate, average win, and average loss.

- Stops are unnecessary if the thesis is strong: Strong conviction does not change the distribution of possible outcomes. A stop recognizes the possibility of being wrong or early.

- Stops get hunted: Price often trades through obvious levels because liquidity concentrates there. This is a feature of order-driven markets, not personal targeting. The solution is thoughtful placement informed by volatility and structure, not the abandonment of risk control.

- Always move stops to avoid losses: Moving a stop farther from the original invalidation increases risk without new information. If new information truly changes the thesis, the plan should define how to act. Ad hoc widening introduces uncontrolled risk.

- Wide stops are always safer: Wider stops can reduce the chance of being shaken out, but they increase per-trade risk if position size is not adjusted. Safety depends on the entire risk framework, not a single parameter.

Practical Examples

Examples illustrate mechanics rather than prescribe actions. Numbers below are for illustration only.

Example 1: Fixed price stop and position sizing. Suppose a share trades at 50. A trader defines invalidation at 47.50. The stop distance is 2.50 per share. If the risk budget per trade is 250, the position size that aligns with the stop is 100 shares, ignoring slippage and commissions. If the stop is hit at 47.50, the planned loss is approximately 250. If the market gaps to 47.00 on the open, the realized loss would be about 300 plus costs. The lesson is that the stop defines the risk unit, while actual fills depend on conditions.

Example 2: Volatility-adjusted stop. Suppose a futures contract has an average true range of 10 points. The trader sets the stop at 1.5 times ATR from the entry to account for typical noise. The unit risk is then 15 points times the dollar value per point of the contract. Position size is chosen so that the dollar risk matches the plan. If volatility doubles, a fixed 15-point stop may become too tight. A volatility-based approach adapts the distance, keeping the stop aligned with current conditions.

Example 3: Trailing stop behavior. Assume a long position gains 5 percent and the stop trails by a fixed 3 percent from the highest price since entry. The stop rises as the trade advances, never moving downward. If price pulls back by 3 percent from its high, the stop triggers and locks in a portion of the gain. This increases the likelihood of exiting before the absolute peak but reduces the chance of a profitable trade turning into a loss after a meaningful run.

Example 4: Time-based exit. A position is opened with the expectation of a near-term catalyst. If price fails to move meaningfully after the event and liquidity deteriorates, the plan may include exiting within a set time window. This protects capital from stagnation and opportunity cost, acknowledging that non-movement can also represent information.

Example 5: Gap and stop limit trade-off. A stop market would exit regardless of how far the market gaps, prioritizing the reduction of risk. A stop limit might avoid an extreme fill by limiting the acceptable price but risks remaining in the position if the market never trades back to the limit. The choice hinges on whether the primary objective is certainty of exit or control of price.

Integrating Stop Losses Into a Broader Exit Plan

A stop loss is one part of a complete exit framework. Other exits may include profit targets, timeouts, and conditional exits based on information changes. An exit plan defines their priority and interaction. For example, a plan might specify that the stop is always honored, with profit-taking rules operating only while the stop remains intact. Alternatively, a trailing stop may replace a fixed target once a certain threshold is reached. What matters is internal consistency and clarity about which rule governs at each stage.

Plans can also specify handling of partial exits. Reducing size into strength can lower risk while preserving the core position. However, partial exits complicate record-keeping and performance evaluation unless R-multiples are calculated for each leg. Consistent accounting ensures that results reflect the true risk taken.

Regulatory and Broker Considerations

Not all venues support all stop types. Some brokers simulate stops on their servers and send market or limit orders only when the trigger conditions are met. Others place stop orders directly on the exchange. Day-only and good-til-canceled durations differ across markets. Order visibility can vary, affecting whether a stop is exposed to the book. In some jurisdictions, certain order types have been restricted or modified over time for investor protection or operational reasons.

Linked order functionality such as OCO, which pairs a stop with a profit-taking order so that one cancels the other when filled, can enforce discipline by preventing over-commitment. The availability and exact behavior of such features should be verified with the specific venue and broker. Understanding these mechanics in advance prevents surprises during fast markets.

When Stop Losses May Not Fit the Instrument

Some instruments have characteristics that complicate traditional stop placement. Illiquid small-cap equities can jump across levels with sparse prints. Options combine price dynamics with changing implied volatility, which means underlying price stops translate imperfectly to option prices. Thinly traded futures and certain crypto pairs can exhibit abrupt wicks that frequently touch nearby stops. In such cases, participants often adapt through wider stops paired with smaller size, volatility-based distances, or risk-defined structures that cap losses by construction. The common thread is explicit downside control that fits the instrument’s mechanics.

Measuring Stop Effectiveness

Stop quality can be evaluated using statistics that capture both outcomes and process:

- Maximum adverse excursion: The worst unrealized drawdown experienced before exit. If MAE often exceeds the stop distance, placement may be too tight relative to market noise.

- Distribution of R-multiples: The spread of losses and gains in units of initial risk. The shape of this distribution reveals whether losses are controlled and whether gains offset them.

- Slippage analysis: Average and worst slippage on stops during normal and stressed conditions, segmented by instrument and time of day.

- Stop-out frequency and reentry rate: How often a position exits at the stop and subsequently moves in the original direction. High rates may prompt a review of volatility assumptions and timing rather than abandoning stops.

- Duration to stop: The typical time between entry and stop-out. Very short durations can indicate either too-tight stops or entries timed during unstable conditions.

These diagnostics turn abstract discussion into concrete evidence. Over time, the stop framework can be refined to match the behavior of the instruments and the holding period.

Ethical and Operational Considerations

Consistent risk control protects not only capital but also decision quality. Clear rules reduce the incentive to average into losers without a defined plan, which can turn manageable drawdowns into catastrophic outcomes. Operationally, documenting stop logic and order behavior supports compliance for those who must report their processes. It also facilitates continuity if systems fail, since rules can be executed manually when needed.

Limitations and What Stops Do Not Do

A stop does not convert a poor thesis into a good one. It does not ensure profitability, prevent slippage in gaps, or eliminate the need for diversification and sizing discipline. It also cannot compensate for entries that are consistently mistimed. A stop is a risk boundary, not a performance guarantee. Its value lies in shaping the distribution of outcomes so that no single loss dominates the long-term record.

Conclusion

A stop loss is a simple idea with profound implications. By defining the point of invalidation and enforcing an exit when that point is reached, it keeps losses in proportion to a plan. Its effectiveness depends on realistic placement, alignment with position sizing, and respect for execution realities such as slippage and gaps. When used consistently and evaluated with appropriate metrics, stop losses support the two goals that matter most in risk management: capital preservation and long-term survivability.

Key Takeaways

- A stop loss is a predefined exit rule that bounds downside by specifying an invalidation level ahead of time.

- Stops shape the loss distribution but do not guarantee the exit price due to slippage and gaps.

- Order type, placement logic, and market microstructure determine how well a stop performs in practice.

- Stop placement and position sizing must be planned together to keep risk per trade consistent.

- Effectiveness improves with consistent execution, post-trade analysis, and adaptation to instrument characteristics.