Profit targets are often discussed as a way to lock in gains, but their deeper purpose is risk control. By specifying where gains will be realized before a position is opened, a trader converts uncertain future outcomes into a more predictable distribution of results. This conversion stabilizes the equity curve, contains variability in holding periods, and makes position sizing more coherent. Profit targets do not forecast the future, and they do not guarantee improved performance. They are a rule for exiting based on predefined conditions that limit exposure to adverse reversals and reduce the behavioral costs of discretionary decision making.

What Is a Profit Target

A profit target is a predefined exit level or condition that triggers an order to realize gains on a position. It may be expressed as a price level, a return multiple relative to initial risk, a volatility-adjusted distance, a time-based rule, or a conditional event such as a change in volatility or liquidity. Profit targets can apply to the entire position or to a portion of it. They can be static, where the level does not change after entry, or dynamic, where the level adjusts according to a rule, for example a trailing exit that climbs as price moves favorably.

Two characteristics distinguish a professional definition:

- Precommitment. The level or rule is specified before or at the moment of entry, which reduces noise from in-trade emotions such as fear of giving back gains or fear of missing out.

- Risk orientation. The target is part of a complete exit plan that also includes a stop loss or an invalidation rule. Together, they bound both tails of the distribution of outcomes.

A profit target is not a prediction that price will reach a particular point. It is an if-then statement. If the specified condition occurs, then the position will be exited according to the rule. That focus on conditioning rather than predicting is what makes profit targets a risk tool.

Why Profit Targets Matter for Risk Control

Profit targets contribute to risk control in several interconnected ways. They shape the payoff distribution, compress the variance of outcomes, and limit path dependency in execution.

1. Bounding the right tail. An open position has theoretically unlimited upside and the potential to retrace sharply before an exit occurs. A target truncates the right tail by forcing a decision to realize gains within a bounded region. This reduces the probability that a winning trade turns into a loss after a sharp reversal. The trade-off is a reduction in maximum possible gain, which is an intentional exchange for stability.

2. Stabilizing the equity curve. Equity curves become smoother when large winners are realized with a consistent rule rather than left entirely to discretion. Smoother does not mean higher returns. It means lower volatility of returns and fewer prolonged drawdowns caused by giving back profits during late exits.

3. Managing holding period risk. Exposure is a function of time. The longer a position is open, the more it is subject to event risk, liquidity changes, and regime shifts. A well specified target limits average holding time for winning trades and frees capital for the next opportunity, which reduces the compounding of idiosyncratic risks within any single position.

4. Improving consistency in position sizing. Position size depends on expected variability of outcomes. When exit rules are known in advance, particularly both stop losses and profit targets, the distribution of trade outcomes is narrower and sizing can be more consistent across instruments and time.

5. Containing execution frictions. Targets can be paired with appropriate order types that seek favorable execution, for example resting limit orders placed away from microstructure noise. Predefined exits reduce the need for impulsive market orders during fast conditions, which can lower slippage and costs. The trade-off is the possibility of a miss if price touches but does not fill.

Profit Targets, Expectancy, and Distribution Shape

At the system level, the expected value of a trade can be framed as E = p × average win minus (1 − p) × average loss. Profit targets influence both p and average win. Lower targets may increase p but reduce average win. Higher targets may reduce p but increase average win. The role of a target is not to maximize E in isolation, since E is sensitive to estimation error and regime changes. The role is to shape the distribution in a way that is compatible with the trader’s risk budget, drawdown tolerance, and capacity constraints.

Two additional properties deserve attention:

- Variance of returns. For the same E, a distribution with capped right tails often exhibits lower variance than one with uncapped winners. Lower variance can reduce the chance of large drawdowns that threaten survivability.

- Autocorrelation of outcomes. When exits are consistent, serial correlation in trade outcomes often decreases, which helps avoid clusters of large givebacks that occur after strong runs.

Profit targets also interact with stop losses to define an implicit payoff ratio. If a stop is one unit of risk and the target is two units above entry, the payoff ratio is 2 to 1. This ratio alone does not determine edge, but it does bound the set of possible outcomes and helps convert qualitative ideas into a quantitative framework for monitoring performance.

Types of Profit Targets

Profit targets can be organized by how they are defined and adjusted. The choice among them is a risk management decision that should be coherent with holding period, liquidity, and volatility conditions.

- Price level targets. Fixed prices based on prior structure or reference levels. These are simple to communicate and test, but they can be brittle if volatility changes.

- Return or multiple targets. Levels expressed as a multiple of initial risk, often called R multiples. For example, exiting at 2R when the stop risk is 1R. This normalizes exits across instruments with different prices.

- Volatility scaled targets. Distances adjusted by recent volatility measures such as average true range. Scaling can maintain comparable hit rates across regimes with varying noise.

- Time based exits. Realization after a defined number of sessions or hours, regardless of price, under the premise that information decays. Time limits cap exposure to event risk and slippage accumulation.

- Conditional or state based targets. Exits triggered when conditions change, for example a drop in realized volatility, a cross in a regime filter, or a liquidity shift. These aim to exit when the original premise is no longer active.

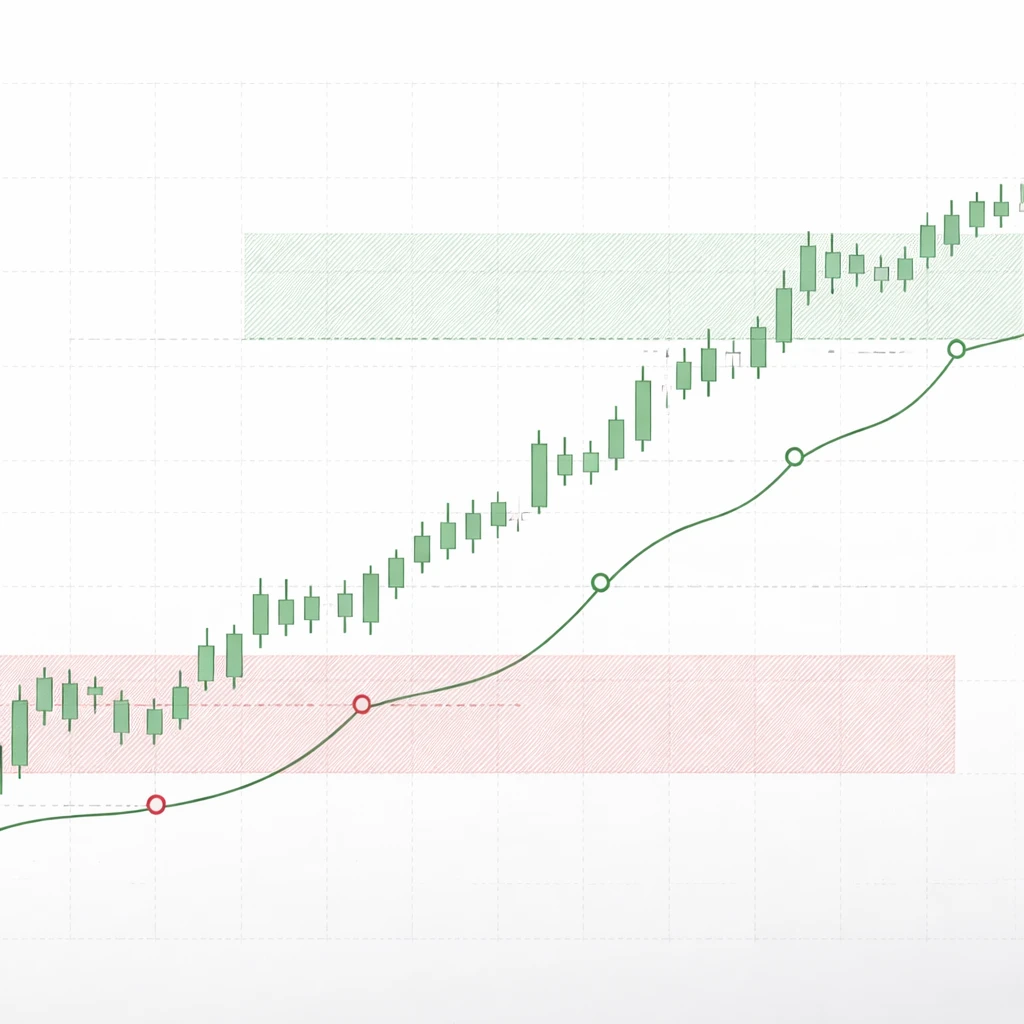

- Trailing profit targets. Dynamic levels that move with favorable price and do not move backward. Trailing rules reduce the gap between unrealized and realized gains while keeping the possibility of larger wins.

- Scaling out. Partial realization at one or more targets, which blends the higher hit rate of closer targets with the potential of farther targets on the remaining portion.

How Profit Targets Function in Real Scenarios

Consider a simple example that uses risk multiples. Suppose a trade is opened with an initial stop 1 percent below entry, which defines 1R. A target is placed 2R above entry. If the target is hit, the realized gain is 2R. If the stop is hit, the realized loss is 1R. Over a series of such trades, the hit rate required to break even is one winning trade for every two losing trades, abstracting away costs. The practical effect is a clear mapping between outcomes and the equity curve that simplifies capacity planning and drawdown estimation.

Now consider a time-based rule. A trader expects that the informational edge decays after five days. The profit target is whichever price is reached first between a preset level and the end of day five. This rule limits prolonged exposure to weekend gaps, earnings events, or policy announcements. The protective effect is not in predicting new information, but in ensuring that positions are not left open beyond the horizon for which the edge, if any, was intended.

Partial exits provide another instructive case. Imagine a two-step plan. Exit half the position at 1.5R, move the stop to breakeven, and attempt to exit the remainder at 3R or by trailing. The first exit harvests gains at a relatively high probability level, which reduces the psychological cost of running the trade. The second exit attempts to capture larger moves without risking the original capital. The trade-off is that average win size is reduced compared with holding the entire position to 3R, and slippage and costs may increase because there are more orders to execute.

All of these scenarios share a theme. The goal is not to squeeze the maximum out of every trade. The goal is to turn uncertain open profits into realized gains in a controlled and repeatable way, with known trade-offs that can be monitored.

Execution and Microstructure Considerations

Profit targets exist in the real world of order books, spreads, and queues. Poor execution can erase their benefits. Several details matter:

- Order type. A resting limit order at the target price generally avoids paying the spread but risks a non-fill if price trades through quickly without providing queue priority. A marketable limit order increases the chance of a fill but may incur worse prices in fast moves.

- Gaps and out-of-hours trading. Targets may be skipped by overnight gaps. If the market opens above a target, the fill can be better than planned. If it opens below for a long, the fill can be worse or not occur. Planning for gap behavior is part of risk control.

- Liquidity concentration. Targets placed at obvious round numbers or prior highs may coincide with heavy resting interest. That can lead to partial fills or stalls. Splitting orders or avoiding crowded levels can improve realized execution, at the cost of added complexity.

- Slippage and costs. Additional partial exits can increase total costs. These costs need to be measured and compared with the risk reduction and behavioral benefits they provide.

- Automation versus discretion. Pre-placing and automating target orders enforces discipline. Discretion can adapt to new information. Blending both approaches requires documented rules that specify when discretion is permitted.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Several beliefs about profit targets persist because they seem intuitively appealing but do not hold up under scrutiny.

- Misconception 1: Profit targets are only about maximizing profits. Targets are about shaping risk and the variance of outcomes. A rule that reduces the chance of giving back gains can be valuable even if it lowers average win size.

- Misconception 2: One fixed target works in all conditions. Volatility, liquidity, and information half-life vary widely across regimes and instruments. A target calibrated to quiet conditions can be either too tight or too loose when volatility shifts.

- Misconception 3: Moving a target farther always lets winners run. Shifting targets after entry can convert a coherent plan into a moving goalpost. The result is often fewer realized gains and a higher chance of round-trips, especially when the shift is driven by emotion rather than a rule.

- Misconception 4: Break-even exits are always safe. Moving to break-even can reduce loss frequency but may increase the number of small exits that cut off potential gains. The effect on expectancy and variance is context dependent and should be measured, not assumed.

- Misconception 5: Backtested optimal targets are reliable. Target distances that look optimal in-sample are subject to data snooping and regime dependence. Robustness checks, out-of-sample tests, and sensitivity analysis matter more than single point optima.

- Pitfall 1: Ignoring transaction costs and taxes. Frequent partial exits can increase explicit and implicit costs. Targets should be evaluated net of these effects.

- Pitfall 2: Using the same target across assets with different microstructure. Instruments with wide spreads or thin depth at the target level may require different handling to avoid slippage and non-fills.

- Pitfall 3: Overriding targets during streaks. Equity highs can tempt a trader to remove targets in pursuit of larger winners. Equity lows can tempt early profit taking for relief. Both erode the logic of the rule set.

Designing Profit Target Rules Within a Risk Framework

Profit targets work best when treated as one component in a complete risk framework that also covers entry validation, stop losses, position sizing, and portfolio constraints.

Coherence with stop losses. The relation between target distance and stop distance sets a payoff profile. A wide target with a tight stop creates a high payoff ratio but usually a lower hit rate. A closer target with a wider stop often has the opposite. The pair should be evaluated jointly using both expectancy and drawdown simulations that reflect actual execution and costs.

Holding period and information decay. The longer the intended holding period, the more a target should reflect changing information and overnight risk. Shorter holding periods may favor precise price targets that exploit local noise. Longer periods may favor conditional targets that respond to regime changes.

Maximum favorable and adverse excursion. Recording the maximum favorable excursion (MFE) and maximum adverse excursion (MAE) for each trade provides a picture of how far trades typically run before reversing and how deep they draw down before becoming profitable. Targets that sit inside typical MFE ranges may miss too many large moves, while targets well beyond MFE medians may rarely be reached. MAE helps set stop distances that align with target choices.

Capacity and diversification. In a portfolio with multiple positions, targets that reduce average holding time can free risk budget for diversification. Conversely, leaving winners open without targets can concentrate risk in correlated exposures for longer than intended.

Drawdown control and survivability. Long-term survivability depends more on limiting deep drawdowns than on achieving maximum single-trade profits. Profit targets contribute by standardizing the conversion of unrealized to realized gains, which reduces variance in equity and speeds recovery after losses.

Measurement and Review

Designing a target is only the first step. Measurement confirms whether the rule produces the intended distribution of outcomes.

- Trade logs. Record planned target levels, realized exit prices, slippage, order type, whether price touched the level without filling, and whether any discretionary override occurred. Note MFE and MAE for each trade.

- Distribution analysis. Examine the histogram of R multiples for wins, the win rate conditional on market regime, and the variance of R across time. Stability is more valuable than peak metrics that lack robustness.

- Scenario drills. Test how the target behaves during volatility spikes, earnings seasons, or macro events. Identify whether the rule leads to clustered non-fills or excessive partial fills.

- Change control. Adjustments should be incremental and documented, with a defined evaluation window. Frequent changes can produce the illusion of improvement while increasing fragility.

Behavioral Dimensions

Profit targets reduce the cognitive load during trades by providing a predetermined action plan. They limit rumination about whether to take profit now or hold for more. This reduces the likelihood of late exits triggered by fear after small pullbacks. Targets also help manage regret. Realized gains can be evaluated against the plan rather than against the eventual high, which is unknowable in real time.

At the same time, targets can create new behavioral risks. If a target is missed by a small amount and price reverses, frustration can lead to chasing or abandoning the plan on the next trade. The antidote is to treat individual outcomes as draws from a distribution and to focus on process metrics, such as percentage of trades executed according to plan and average slippage relative to the target.

Putting Targets in Context with Other Exits

A complete exit plan contains at least three elements: a stop loss for invalidation, a profit target for realization, and rules for exceptions such as timeouts or regime changes. These exits can be blended. For example, a position could have a primary profit target and an alternative conditional exit if volatility collapses before the target is reached. Alternatively, an initial static target can convert to a trailing exit after a threshold is hit. The key is internal consistency and documentation so that trade outcomes can be attributed to known rules rather than ad hoc reactions.

Limits of Profit Targets

Profit targets do not eliminate risk. They shift and shape it. Targets can be skipped during gaps, fail to fill in thin markets, or be rendered suboptimal when conditions change rapidly. They can also reduce expected value if set too conservatively. The point is not to remove uncertainty, but to manage it so that the distribution of outcomes supports the continued operation of the trading process through many cycles.

Closing Remarks

Profit targets are exit rules framed in the language of risk. They translate favorable moves into realized gains with known trade-offs. When paired with coherent stop losses, position sizing, and monitoring, they help protect capital, stabilize the equity curve, and increase the probability of long-term survivability. The discipline of precommitment and the measurement of process quality are as important as the specific distances chosen. What matters is that targets are designed to serve risk control objectives, tested for robustness, and executed with consistency.

Key Takeaways

- Profit targets are predefined exit rules that convert uncertain open profits into realized gains, primarily to control risk and variance rather than to forecast outcomes.

- Targets work best when integrated with stop losses, position sizing, and holding period assumptions to form a coherent risk framework.

- The placement and type of target shape the distribution of trade results, including hit rate, average win, variance, and drawdown behavior.

- Execution quality, liquidity, gaps, and costs materially affect realized outcomes and must be accounted for when evaluating target rules.

- Misconceptions such as one-size-fits-all targets and overreliance on backtested optima can undermine risk control and long-term survivability.