Exiting losing trades is a central element of risk management. It is the deliberate act of closing a position that has moved against the thesis or risk parameters in order to limit further loss. While entrances often receive more attention, it is the quality and consistency of exits that largely determine whether a trading process can endure. The goal is not to eliminate loss. The goal is to confine loss to a planned scale that the account can absorb without jeopardizing long-term participation in the market.

Loss containment is not only a matter of personal comfort. It is a mathematical necessity. A modest drawdown requires a disproportionately larger subsequent gain to recover, and this asymmetry compounds as losses deepen. Over many trades, the ability to stop small losses from becoming large ones has a direct effect on the stability of returns, the likelihood of ruin, and the capacity to learn from a consistent process.

Defining Exiting Losing Trades

In risk management terms, exiting a losing trade is the execution of a pre-specified or rule-governed decision to close a position when its adverse movement reaches a defined threshold. The threshold can be framed in several ways, such as a monetary amount, a percentage of entry price, a volatility-based measure, a time-based rule, or a rule tied to a change in the underlying thesis. The exit can be implemented with working orders or managed discretion, but it is planned in advance and executed when criteria are met.

This definition is intentionally agnostic about strategies, instruments, or timeframes. Whether the position lasts seconds or months, the core idea is the same. A trader defines the maximum acceptable loss for the position and commits to closing the trade when that limit is reached. This is distinct from abandoning the trade opportunistically or emotionally. It is also distinct from predicting market direction. It is a rule about what to do if the market moves in a way that violates the risk premise of the trade.

Why Exiting Losing Trades Is Critical to Risk Control

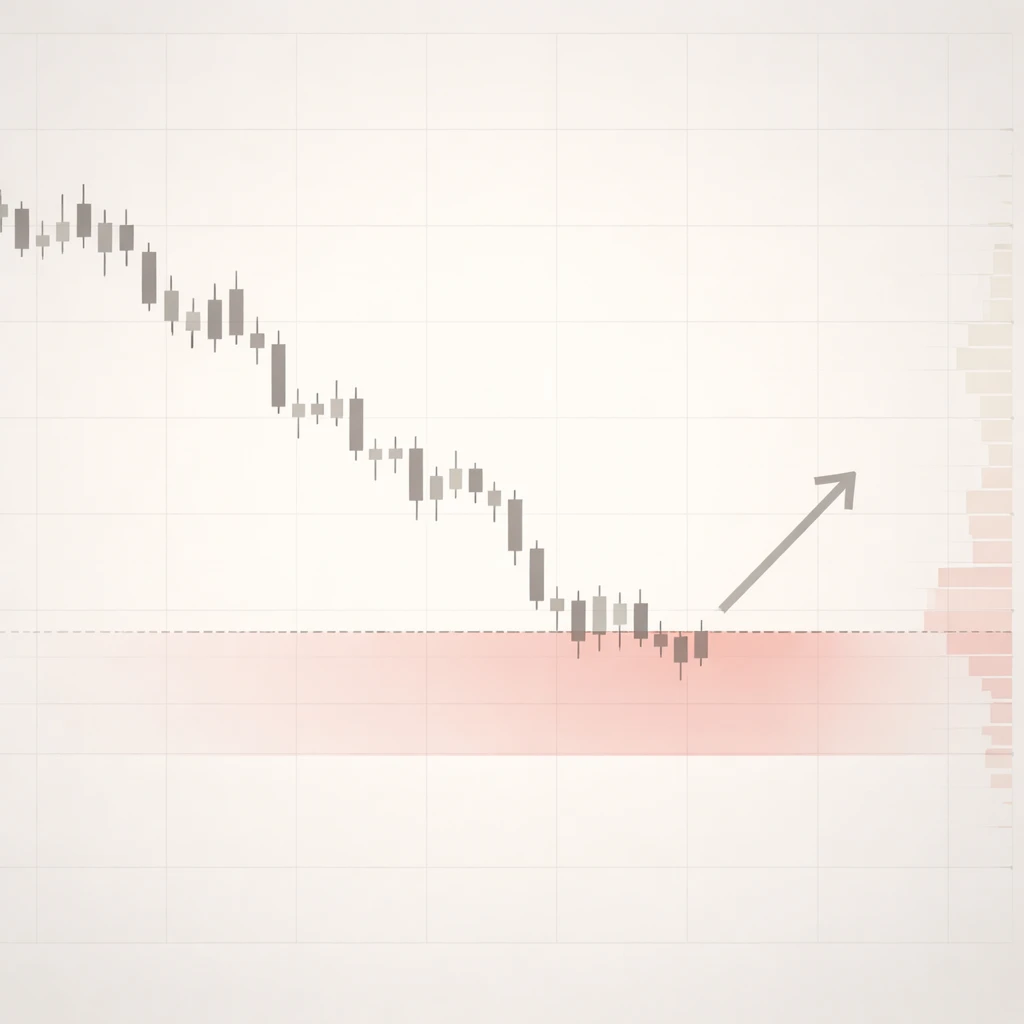

The asymmetry of losses

Losses scale nonlinearly with recovery requirements. A 10 percent loss requires an 11.1 percent gain to return to breakeven. A 50 percent loss requires a 100 percent gain. This convexity is unforgiving. Exiting a position before it reaches severe drawdown limits the recovery burden that future trades must carry. In practical terms, smaller controlled losses preserve optionality, which is the ability to redeploy capital into new opportunities without first overcoming a large deficit.

Variance and survivability

Expected return is only part of the equation. The variance of returns influences whether a process can survive long enough to realize its expectation. Large unbounded losses increase both variance and tail risk, which raises the probability of breaching capital constraints. By enforcing exits on losing trades, a trader clips the left tail of the return distribution. The mean of outcomes may not change dramatically in the short run, but the distribution becomes more stable. Stability increases the likelihood of staying solvent and engaged during adverse periods.

Compounding and time in the market

Compounding benefits from uninterrupted participation. Deep drawdowns reduce the base on which future gains compound and lengthen recovery time. Traders who keep losses small can maintain a more consistent equity curve, which allows the capital base to compound more steadily. Exiting losing trades is therefore a mechanism that protects the compounding process rather than a mere act of damage control.

How Exits Work in Practice

There are several common frameworks for defining and implementing exits from losing positions. These are not strategy recommendations. They are descriptions of mechanisms that practitioners use to codify risk limits.

- Price based limits. The exit is triggered when price reaches a level that invalidates the risk premise. The level can be defined as a distance from entry or by structural features of price action. The intent is to bound the maximum adverse excursion.

- Volatility based limits. The exit adapts to the instrument’s variability. For example, the threshold scales with an estimate of recent volatility so that stops are neither trivially tight in a quiet regime nor dangerously loose in a turbulent regime.

- Time based limits. The position is closed if the expected behavior does not materialize within a defined period. Time stops recognize that opportunity cost and regime drift can degrade the original thesis even if price has not violated a level.

- Capital at risk limits. The exit is framed in currency terms relative to account size. For instance, a position may have a fixed capital loss budget. When that budget is consumed, the position is closed irrespective of other signals.

- Thesis invalidation rules. The exit is triggered by new information or structural changes that contradict the reason for being in the trade. This requires pre-writing the thesis so that invalidation criteria are objective rather than retrospective rationalization.

Implementation can be mechanical or discretionary. Mechanical implementation uses standing orders that execute when conditions are met. Discretionary implementation uses active monitoring, often with alert thresholds, followed by manual execution. Both approaches face execution risks such as slippage, gaps, and liquidity frictions. The key difference lies in the reliance on discipline and the potential for delay under stress.

The Economics of Cutting Losses

Exiting a losing trade incurs a certain cost. The position is closed at a loss, and that loss is realized. The alternative is to hold and hope that the loss reverses. The evaluation should not pivot on hope. It should compare the expected cost of staying with the risk-limited cost of leaving.

Consider an account that risks 1 percent of capital per trade as a policy. If a position reaches that limit, closing it preserves the account for the next opportunity. If the position is held and the loss expands to 3 percent, the account now needs multiple subsequent trades to recover. During that time, optionality is reduced, and the trader is more vulnerable to correlated market stress. There is also a psychological cost. Larger losses raise emotional temperature, which tends to degrade decision quality on subsequent trades.

Capital efficiency is another consideration. A losing position that ties up margin or capital cannot be used elsewhere. By exiting at a defined loss, the trader frees resources for new exposures that may have better risk return prospects. This is not a prediction about the next trade. It is a policy about allocating scarce capital to positions that still meet their risk criteria.

Behavioral Barriers to Timely Exits

Well documented biases complicate the act of exiting losing trades. Loss aversion makes realized losses feel worse than equivalent gains feel good, which encourages holding to avoid the pain of recognition. The disposition effect nudges traders to sell winners too early and hold losers too long. Anchoring leads to fixation on the original entry price, which is irrelevant to current risk. Escalation of commitment can follow, as additional resources are deployed to justify or rescue the initial decision.

Overcoming these biases requires structure. Predefining exit rules at the time of entry reduces the temptation to renegotiate under stress. Checklists can make criteria explicit. Journaling helps identify personal patterns such as widening stops after adverse moves. None of these tools eliminate uncertainty, but they reduce the degrees of freedom that enable biased decisions.

Practical Scenarios

Example 1: Equity position drawdown and recovery math

Assume a trader buys shares at a given price with an initial risk limit that caps loss at 2 percent of account equity. The stock declines and breaches the limit. Closing the position fixes a 2 percent loss. If the trader holds and the loss deepens to 8 percent of the account, the required recovery just to return to the starting capital is roughly 8.7 percent. If the broader portfolio also faces pressure, those additional recovery requirements may accumulate across positions. The initial 2 percent loss is manageable within the planned risk budget. The 8 percent loss consumes future capacity and time.

Example 2: Leveraged futures and margin risk

In leveraged instruments, small adverse moves can generate margin calls or automatic liquidations. Suppose a futures position is initiated with a stop that would realize a loss equal to a small fraction of the account. If the stop is removed during stress, a sharp move can multiply the loss relative to capital before manual intervention is possible. The discipline to exit at the predefined threshold is, in such contexts, a protection against nonlinear losses that arise from leverage and market gaps.

Example 3: Time stop and opportunity cost

A trader enters a position anticipating that a catalyst will drive movement within several days. The price drifts without meaningful progress. Even if the position is not underwater, the thesis hinges on timing. Closing the trade after the time window expires acknowledges that the situation did not unfold as expected and returns capital to inventory. The exit is justified not only by loss control but also by a desire to maintain alignment between position and thesis.

Common Misconceptions

- “Stops are always hunted.” Markets can cluster orders around obvious levels. That does not imply intent or guarantee that stops are systematically targeted. More importantly, the possibility of being stopped out near a local extreme does not negate the function of the stop, which is to limit loss size. The occasional frustrating exit is the price paid for insurance against larger adverse moves.

- “Widening a stop reduces risk.” Widening may reduce the probability of being stopped out, but it increases the size of the loss when it occurs. Risk is a function of both probability and magnitude. A lower stop frequency with larger losses can raise expected loss and tail risk.

- “A small account cannot afford to use stops.” A small account cannot afford large, uncontrolled losses. Sizing and exit rules can scale with capital. The principle of defining a maximum loss per position remains applicable regardless of account size.

- “Mental stops are sufficient.” Mental stops rely on perfect attention and willpower. Under stress or during fast markets, execution can lag intention. Some traders use working orders or alerts to bridge the gap. If discretion is used, it must be supported by a process that addresses execution risk.

- “Options replace the need for exits.” Options can cap risk, but they introduce different dynamics, including time decay, changing volatility, and gap behavior at expiration or events. Position risk still requires clear definitions of acceptable loss and conditions for closing or adjusting.

Operational Realities: Slippage, Gaps, and Liquidity

Even a well designed exit is exposed to execution frictions. Slippage occurs when the fill price differs from the expected level due to order book depth or speed of movement. Gaps can skip over stop levels during overnight sessions or news events, resulting in worse fills than planned. Illiquid instruments can widen spreads and delay execution.

These realities call for humility in planning. Risk limits should acknowledge that fills may be less favorable than the stop price. Position sizing can incorporate a buffer for expected slippage in the relevant instrument and timeframe. Where gap risk is material, some traders diversify entry times, reduce overnight exposure, or use instruments that trade nearly around the clock. The central point is that exit planning includes the pathway to execution, not only the level on a chart.

Designing a Coherent Exit Policy

An exit policy gains strength from clarity, consistency, and testability. Clarity means the criteria are unambiguous and documentable. Consistency means the criteria apply across trades so that results are attributable to the process rather than discretionary variability. Testability means the rules can be evaluated against historical or forward data to understand how they behave across regimes.

A practical policy often includes the following elements:

- Predefined maximum loss per position. A limit expressed in account terms that scales with capital and risk tolerance.

- Rule hierarchy. Guidance for conflicts, such as what takes precedence if a time stop and a price stop are both near activation.

- Execution method. Whether exits are automated, discretionary, or a combination, and what safeguards exist for fast markets.

- Review loop. A process to examine each stopped trade, not to move the goalposts, but to learn whether thresholds remain appropriate for the instrument and regime.

The objective is to build a repeatable pattern of behavior that does not depend on moment to moment emotion. A coherent exit policy is an instrument of discipline, not a promise of perfection.

Measuring Exit Quality

Exit quality can be assessed with metrics that describe both the size and distribution of losses. Useful measures include average loss per losing trade, median loss, the variability of losses, and the frequency of losses that exceed predefined limits. Maximum adverse excursion analysis can reveal whether stops are consistently tighter or looser than necessary for the chosen approach. R multiples, which scale outcomes by initial risk, help compare trades across different sizes and instruments.

Quality assessment should focus on whether exits are doing their job, which is to cap losses predictably. An exit that frequently allows losses beyond the planned limit suggests either execution problems or thresholds that are not aligned with the instrument’s volatility. Conversely, exits that trigger too often with negligible adverse excursion may indicate thresholds that are unrealistically tight for the noise level. The intent is not to chase the perfect stop that never triggers at the low. It is to calibrate around the process so that losses are contained without stifling the approach.

Portfolio Context and Correlation

Exiting losing trades cannot be evaluated solely at the single position level. Portfolio losses can cluster across correlated positions during stress regimes. If several positions share a common risk factor, their losses may accelerate together. A portfolio level loss limit can supplement position exits by closing or reducing exposures when total drawdown reaches a threshold. This acknowledges that diversification can contract precisely when it is most needed.

Correlation sensitivity also affects how individual stop levels aggregate. Multiple positions each risking a small fraction of the account might collectively represent a large exposure to a single catalyst or macro variable. Planning exits with an eye to shared drivers reduces the chance that several supposedly independent positions exit simultaneously in a larger than expected drawdown.

Special Cases: Events and Overnight Risk

Scheduled announcements and earnings releases can change the distribution of returns. Gaps are more probable, and liquidity can thin. If holding through such events, exit planning should assume that price can move discontinuously. That may involve acknowledging that the realized loss could exceed the stop level. The policy decision is whether to accept that event risk or to avoid holding through events when the gap risk exceeds the tolerance built into stop planning.

Overnight and weekend risk introduces similar considerations. Instruments that do not trade continuously can open far from the previous close. Exits that rely solely on intraday triggers may not function as expected. Planning for these gaps is a matter of aligning the exit mechanism with the operating hours and behavior of the instrument.

Learning From Exited Trades

Every executed exit creates data. A disciplined review can surface whether a thesis was invalidated for the reasons anticipated, whether the volatility environment shifted, or whether execution caused an outsized loss relative to the plan. Journals that capture the intended exit logic, actual fill details, and contextual notes help distinguish process flaws from normal variance.

Over time, such reviews can lead to refinements. Thresholds might be adjusted to match the typical noise of a market. Time stops may shorten in regimes where trends decay quickly. Position sizing might be recalibrated if realized slippage consistently exceeds the assumption. The purpose of review is to update the process, not to avoid the pain of realizing a loss. Losses that are smaller than planned and consistent with rules are evidence that the process is working.

Long Term Survivability

Survivability is the capacity to remain engaged in the market across cycles without breaching risk limits or psychological tolerance. Exiting losing trades preserves this capacity by limiting the accumulation of large drawdowns, protecting the compounding base, and maintaining decision quality under stress. Even approaches with modest edge can compound acceptably if variance is controlled. Conversely, even strong approaches can fail if losses are allowed to run without discipline.

There is also a human dimension. Large, unmanaged losses erode confidence and can trigger reactive behavior that departs from the process. A consistent exit framework lowers the emotional amplitude of trading by replacing ad hoc decisions with known actions. Reduced emotional volatility helps sustain attention and focus, which are prerequisites for learning and adaptation.

Putting the Concept in Context

Exiting losing trades is a risk control principle that stands alongside position sizing, diversification, and scenario awareness. It does not guarantee profitability. It does not turn a poor thesis into a good one. What it does is define the boundary of acceptable loss so that a trader can operate within known limits. Within those limits, learning is possible. Outside them, capital erosion and stress can end the process before it matures.

Markets will produce periods where exits feel untimely. There will be stops just before reversals and periods where volatility regimes shift, making exits appear noisy. These episodes are not evidence that exits are unnecessary. They are reminders that risk management is about controlling outcomes, not predicting them. The cost of occasional premature exits is the premium paid for resilience during the periods when adverse moves do not reverse.

Key Takeaways

- Exiting losing trades is a preplanned act that caps downside at a defined threshold to protect capital and preserve optionality.

- Losses are asymmetric. Preventing deep drawdowns reduces recovery time and stabilizes compounding.

- Execution realities such as slippage, gaps, and liquidity must be incorporated into exit design and position sizing.

- Behavioral biases encourage holding losers. Structure and documentation support discipline at the moment of decision.

- Exit effectiveness is measured by the predictability and containment of losses across trades, not by avoiding every premature stop.