Drawdowns are the language of loss in portfolio management. While returns describe how capital grows, drawdowns reveal how it is impaired along the way. Among drawdown measures, maximum drawdown receives special attention because it marks the worst peak-to-trough loss experienced over a period. It is not a prediction and it is not a guarantee. It is a historical fact, and a compact signal of path risk that materially shapes a trader’s survivability.

What Is Maximum Drawdown?

Maximum drawdown (often abbreviated MDD) is the largest percentage decline from any historical high in the cumulative value of an account or strategy to a subsequent low before a new high is reached. It is computed from the equity curve, not from isolated period returns. The equity curve incorporates compounding, and the drawdown is measured relative to each new high-water mark.

In words, scan the equity curve from start to finish. Each time the curve makes a new high, record that high-water mark. From that point forward, track how far the curve falls before it either recovers to a new high or sets a deeper trough. The maximum drawdown is the largest of all such peak-to-trough percentage declines over the period studied.

Formal Definition

Let V(t) denote the equity value at time t. Define H(t) as the running maximum of V up to time t. The drawdown at time t is D(t) = 1 − V(t) ÷ H(t). The maximum drawdown over the sample is the maximum of D(t) across all t. If V and H are measured consistently, D(t) is always between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates no drawdown and values closer to 1 indicate large losses from the high-water mark.

This definition is path dependent. Two strategies with the same average return and volatility can have very different maximum drawdowns if one experiences clustered losses and the other alternates small gains and losses.

Why Maximum Drawdown Matters for Risk Control

Maximum drawdown captures the magnitude of loss that must be endured during adverse sequences. It is directly tied to three practical issues: capital impairment, behavioral tolerance, and time to recovery.

Capital impairment matters because loss arithmetic is asymmetric. A 25 percent loss requires a 33.3 percent gain to recover to the prior high. A 50 percent loss requires a 100 percent gain. Maximum drawdown provides a concrete upper bound on the historical severity of this asymmetry.

Behavioral tolerance refers to the ability to adhere to a process while the account is underwater. Even robust strategies can fail in practice if their drawdowns exceed what stakeholders can tolerate. Maximum drawdown is often used as a yardstick in due diligence, mandates, and internal risk limits because it is easy to interpret.

Time to recovery affects capital availability. Long drawdowns can coincide with margin constraints, redemptions, or opportunity costs. While maximum drawdown measures the depth of the hole, it also invites examination of how long it took to climb back out. Both depth and duration influence survivability.

How to Compute Maximum Drawdown

Step-by-Step Procedure

Suppose you have a sequence of daily equity values for a strategy. The steps are straightforward:

- Compute the running high H(t) = max{V(s) for s ≤ t}.

- Compute the drawdown series D(t) = 1 − V(t) ÷ H(t).

- Identify the maximum value of D(t). This is the maximum drawdown for the sample.

It is essential that the equity series V(t) reflects the full economic value of the account, including closed trade profits and losses, open trade mark-to-market, commissions, fees, slippage, financing costs, and any cash flows that change capital.

Numerical Example

Consider an equity path that starts at 100,000. It rises to 120,000, then falls to 90,000, and later climbs to 130,000.

- The high at 120,000 sets the waterline. The fall to 90,000 represents a drawdown of 1 − 90,000 ÷ 120,000 = 25 percent.

- When the equity later reaches 130,000, a new high-water mark is established and the previous drawdown is complete. Any subsequent decline is measured from 130,000.

Over this window, the maximum drawdown is 25 percent. If the equity had only fallen to 96,000 before making a new high, the drawdown would have been 20 percent. The procedure is the same whether the data are daily, weekly, or intraday. The measurement frequency affects the result because more granular data can reveal deeper intraperiod troughs.

Practical Data Considerations

- Frequency sensitivity. Using monthly data can understate drawdowns relative to daily or intraday data because interim lows are not observed.

- Cash flows. Deposits and withdrawals change capital but are not investment gains or losses. To avoid distortions, adjust the equity series to separate performance from external cash flows or use a return-based equity curve that reinvests at the strategy’s rate.

- Costs and slippage. Omitting trading costs or slippage usually understates drawdowns. A realistic equity series is necessary for a meaningful measure.

- Data revisions. Backfills, survivorship bias, and price revisions can contaminate historical equity. Document data sources and processing steps.

- Position valuation. Marking to last trade can be noisy for illiquid assets. Some practitioners use mid quotes or model-based marks, which can smooth drawdowns. Understand the valuation method before interpreting results.

Interpreting Drawdowns in Real Trading

Capital Impairment and Recovery Math

Drawdown depth translates directly into required recovery. If a portfolio declines from 1.00 to 0.80, the drawdown is 20 percent and the required gain to return to 1.00 is 25 percent. This asymmetry is central to capital preservation. Large drawdowns consume risk budget and extend recovery times, which can constrain future flexibility.

The compounding effect magnifies differences. Two paths with the same average return can produce very different terminal wealth if one endures a deep drawdown early, because subsequent percentage gains are applied to a smaller base.

Duration and Time Under Water

Maximum drawdown measures depth, not duration. Two strategies can share a 20 percent maximum drawdown, but one might recover in weeks and the other in years. Many practitioners track the full distribution of underwater periods, including the average time under water, the longest time to recovery, and the proportion of time spent below the high-water mark. These measures complement maximum drawdown and help set realistic expectations around capital availability.

Leverage, Liquidity, and Path Dependence

Leverage increases exposure to both gains and losses. For a given return volatility, higher leverage tends to amplify drawdowns and increase the probability of breaching margin thresholds. Illiquidity can further deepen drawdowns by widening bid-ask spreads and increasing slippage during exits. Path dependence matters because losses that cluster can trigger deleveraging or forced liquidations that would not occur under smoother paths.

Maximum Drawdown and Other Risk Measures

Volatility

Volatility summarizes the dispersion of returns around a mean. Maximum drawdown summarizes the worst historical path impairment. A strategy can have low volatility but a large maximum drawdown if it occasionally experiences sustained losses. Conversely, a high volatility strategy can have a modest drawdown if gains and losses alternate without long adverse sequences. The two measures inform different aspects of risk.

Value at Risk and Expected Shortfall

Value at Risk (VaR) estimates a quantile of short-horizon loss under a given model and confidence level. Expected shortfall (also called conditional VaR) estimates the mean loss given that the VaR threshold is breached. Both are distributional measures of returns over a specified horizon. Maximum drawdown is a path metric that can unfold over many horizons. A portfolio can meet daily VaR limits yet still experience a large drawdown through a series of small losses. That is why drawdown monitoring often complements VaR in risk frameworks.

Ulcer Index, Calmar Ratio, Sterling Ratio, and CDaR

The Ulcer Index measures the depth and duration of drawdowns by averaging the squared percentage declines below the high-water mark. The Calmar ratio is a performance measure that divides average return by maximum drawdown over a period. The Sterling ratio adjusts for an assumed minimum drawdown hurdle. Conditional drawdown at risk (CDaR) estimates a tail expectation of drawdowns rather than returns. These metrics extend the information content beyond a single worst-case number, although they still inherit the data and model limitations of the underlying equity curve.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Understating Drawdowns With Sparse Data

Using only monthly or quarterly snapshots can hide intraperiod troughs. If a portfolio drops sharply mid-month and partially rebounds by month end, the measured monthly drawdown can be much smaller than the true peak-to-trough loss. Where possible, compute drawdowns on the most granular data that are reliable and available.

Ignoring Fees, Slippage, and Open Positions

Backtests that exclude trading costs or that update equity only upon trade close tend to understate drawdowns. Real-world equity moves with open positions and transaction costs. A mark-to-market equity curve that incorporates realistic costs is essential for credible drawdown estimates.

Start-Date Bias and Regime Dependence

Maximum drawdown depends on the sample window. Starting a backtest at a fortunate time can reduce the measured MDD, while an unfortunate start can inflate it. Market regimes shift, and correlations can change during stress. Historical MDD should be treated as a sample statistic, not as a bound on future loss potential.

Aggregation and Diversification Illusions

Measuring drawdown at the individual strategy level can obscure portfolio-level risk if components become correlated during stress. Conversely, measuring only at the portfolio level can hide dangerous concentration in a single sleeve. It is prudent to examine drawdowns at multiple aggregation levels and under stressed correlation assumptions. Diversification benefits that appear strong in calm markets often weaken when volatility and correlations rise together.

Confusing Recovery With Robustness

A quick rebound from a drawdown does not prove robustness. Recovery speed can be driven by favorable markets rather than process quality. Likewise, a slow recovery does not necessarily imply a weak strategy if the environment was unfavorable. Drawdown analysis should be paired with attribution and sensitivity analysis to isolate drivers.

Using Drawdown to Support Capital Preservation

Capital preservation is about staying solvent and operational through adverse sequences so that the compounding process can continue. Maximum drawdown contributes to that goal by setting expectations for worst-case historical impairment and by informing how much variability in equity a process has tolerated in the past.

Risk Budgeting and Position Sizing Concepts

Many practitioners frame risk in terms of tolerable drawdown at the portfolio and strategy levels. Position sizes, leverage, and concentration are often constrained so that estimated drawdowns remain within a defined budget under a range of scenarios. The goal is not to prevent any drawdown, which is impossible, but to restrict the size of potential equity losses to levels that the capital base and governance can sustain.

Scenario Analysis and Stress Testing

Scenario analysis examines how a strategy might have behaved during past stress periods or under hypothetical shocks. One common technique is to impose stress scenarios on the current portfolio to infer potential drawdown paths. Another is to resample or reshuffle historical returns to create synthetic paths and estimate the distribution of future drawdowns under assumptions about dependence and tail behavior. These exercises do not produce certainties, but they provide a structured way to confront capital with plausible adverse sequences.

Monitoring and Reporting

Ongoing monitoring of current drawdown versus historical drawdown is central to risk oversight. Reports often include the current drawdown, the maximum drawdown to date, the average and longest time under water, and comparisons to predefined tolerance bands. Clear reporting helps align expectations among stakeholders and reduces the likelihood of reactive decisions during stress.

Realistic Examples of Drawdown Behavior

Trend-Following and Mean-Reversion Profiles

Strategies that ride price trends often experience long streaks of small gains punctuated by episodes of whipsaw, where multiple small losses cluster. Their return distributions can be positively skewed but serial correlation in losses can produce extended drawdowns when trends reverse. Mean-reversion strategies can show many small wins with occasional large losses. The average volatility can be similar across both approaches, yet their maximum drawdowns and time-under-water profiles may differ substantially due to path characteristics.

Intraday Versus Multiday Horizons

Intraday strategies that close positions daily may show frequent but shallow drawdowns relative to their high-water marks if risk is tightly managed within the day. Swing or position strategies that hold risk across sessions face overnight gap risk and macro event risk, which can increase the depth of peak-to-trough declines. Neither profile is inherently superior. What matters is the alignment between drawdown characteristics and capital tolerance.

Role of Leverage and Financing

Consider a portfolio with 2 times leverage applied to a baseline strategy. If the unlevered strategy experiences a 12 percent drawdown, the levered version will typically experience roughly a 24 percent drawdown before financing and trading frictions. The amplification can be larger when spreads widen or when funding costs increase during stress. Leverage can also accelerate breaches of margin requirements, which can crystallize losses that might otherwise have been temporary.

Limitations of Maximum Drawdown

Maximum drawdown condenses a complex path into one number. That number is informative, but it has limitations:

- Sample dependence. The measured MDD depends on the start and end of the sample. Different windows produce different maxima.

- Blind to near misses. MDD ignores how often large drawdowns almost occurred. Two strategies can share the same MDD, yet one may spend much more time near deep troughs.

- No timing information. MDD does not reveal how quickly the loss occurred. A 20 percent loss in two days is very different from a 20 percent slow decline.

- Sensitivity to valuation choices. Smoothing in prices or costs can reduce the measured MDD without changing economic risk.

- Nonstationary markets. Structural changes can render past MDD a poor guide to future extremes. Complementary stress scenarios help address this limitation.

Extending the Analysis: Distribution of Drawdowns

Practitioners often supplement MDD with the distribution of drawdown depths and durations across the sample. This can be done by identifying each completed drawdown cycle from peak to trough to new peak and recording its depth and length. The resulting histograms provide a richer picture of typical versus extreme experiences. Conditional drawdown at risk (CDaR) takes a tail expectation of these depths to summarize severe but not necessarily maximal events. Examining both depth and duration distributions helps calibrate expectations about how often significant underwater periods may occur and how long they tend to last.

Implementation Notes for Backtests and Live Trading Records

- Equity curve construction. Build equity from returns that include realistic costs and financing. If the portfolio has cash inflows or outflows, either reconstruct a pro forma equity series net of cash flows or compute a compounded return index that reinvests performance.

- Granularity. Use the most reliable frequency available. If intraday marks are noisy or illiquid, daily closing marks may be more meaningful despite underreporting intraday troughs.

- Auditability. Maintain reproducible code and logs for how drawdowns are computed, including corporate action adjustments, roll methods for futures, and handling of missing data.

- Live versus backtest. Keep results separate. Maximum drawdown in a backtest and in live trading are often different due to learning, slippage changes, and regime shifts.

Communicating Drawdown to Stakeholders

Clear communication of drawdown metrics promotes alignment. Common practices include presenting:

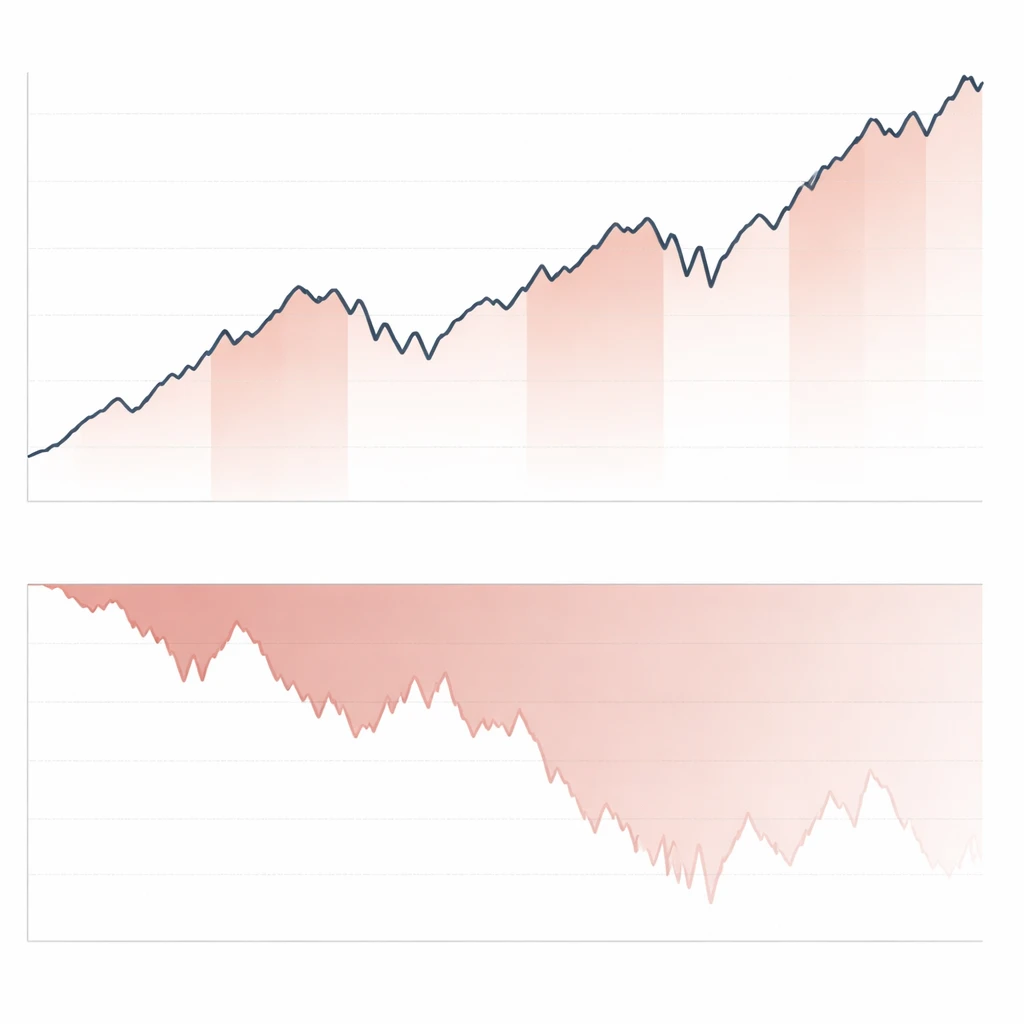

- An equity curve with drawdown episodes visually highlighted.

- An underwater chart showing percentage below the high-water mark over time.

- Summary statistics that include maximum drawdown, current drawdown, average drawdown, longest time under water, and date ranges for major episodes.

Visuals and concise statistics make the path risks tangible. They do not eliminate uncertainty, but they help stakeholders internalize the range of historical experiences and the implications for capital resilience.

Putting Maximum Drawdown in Context

Maximum drawdown is one component of a broader risk mosaic. It should be interpreted alongside strategy design, market structure, liquidity, concentration, and sensitivity to macro shocks. The same measured MDD can carry different meanings across contexts. For example, a 15 percent MDD for a low turnover, highly liquid portfolio may be more manageable than the same figure for a levered, concentrated book that faces potential funding stress. Context determines how much severity can be absorbed without impairing operations.

Key Takeaways

- Maximum drawdown is the largest historical peak-to-trough percentage loss on an equity curve and is a direct measure of path risk.

- It matters for capital preservation because it quantifies potential equity impairment, behavioral tolerance, and time under water.

- Computation requires a realistic, mark-to-market equity series that reflects costs, cash flows, and appropriate data frequency.

- Maximum drawdown complements but does not replace volatility, VaR, or expected shortfall, and benefits from distributional and duration analyses.

- Historical MDD informs expectations, yet it is sample dependent and should be paired with stress tests and scenario analysis to address regime shifts.