Drawdowns are a fact of trading. Even well-conceived processes produce sequences of losses that temporarily push equity below its prior high. The discipline of risk management addresses this reality through explicit rules that restrict risk-taking when losses accumulate. Limits of drawdown control provide a structured boundary for acceptable peak-to-trough loss, with predefined responses when the boundary is reached. Their aim is straightforward. Protect capital and preserve the ability to continue operating long enough for an edge, if present, to express itself.

What a Drawdown Is and Why It Matters

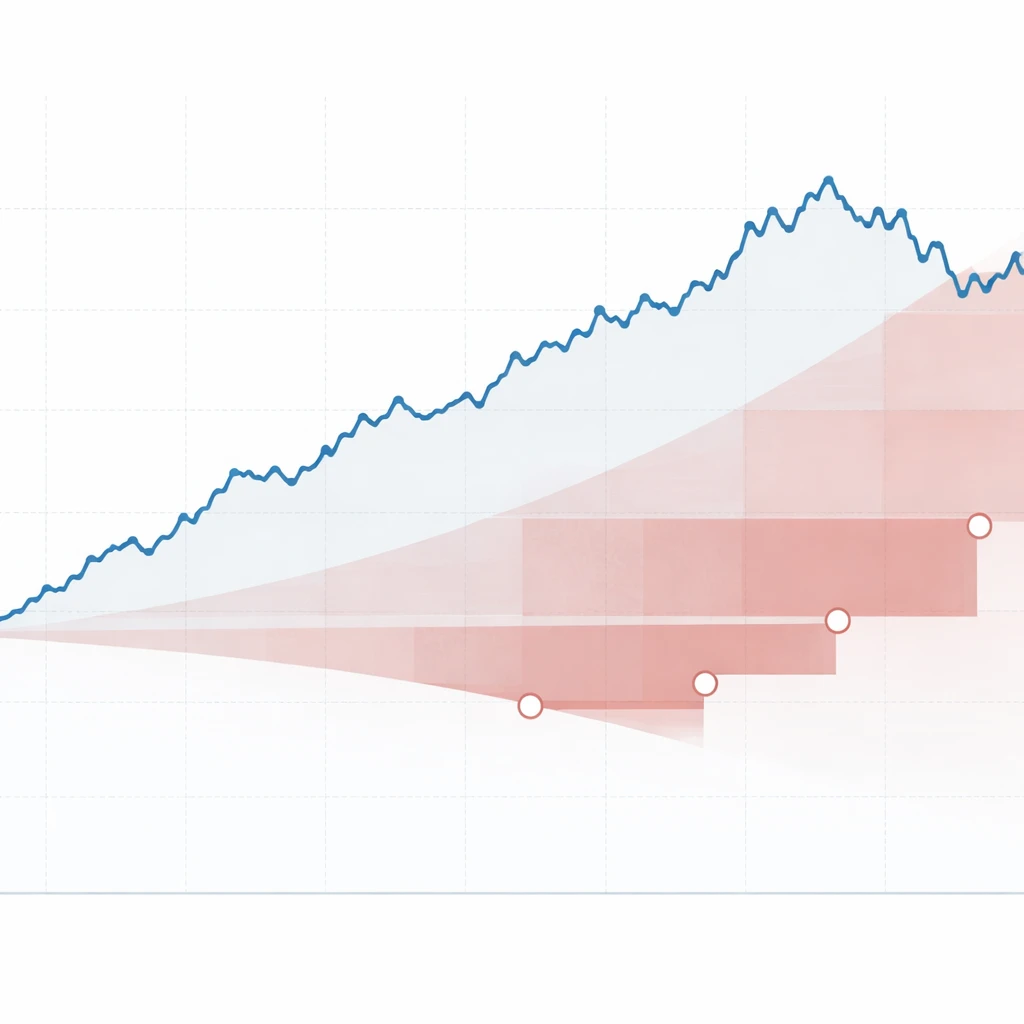

A drawdown is the decline in equity from a historical peak to a subsequent trough, measured on a mark-to-market basis. It captures both depth and duration. The deepest point defines maximum drawdown over the period of observation, while the time spent below the prior high defines the underwater period. Because equity growth is multiplicative, the recovery requirement grows nonlinearly with loss size. A 10 percent decline requires an 11.1 percent gain to recover. A 25 percent decline requires a 33.3 percent gain. A 50 percent decline requires a 100 percent gain. These relationships show why controlling drawdowns is central to capital preservation.

Drawdown is path dependent. Two strategies with the same average return and volatility may exhibit different drawdown profiles because losses can cluster. Serial correlation, volatility regimes, liquidity conditions, and correlation spikes across positions can all concentrate adverse outcomes. Risk management must therefore respond to the path, not only to long-run averages.

Defining Limits of Drawdown Control

Limits of drawdown control are formal constraints that set the maximum allowable decline from an equity peak and specify the actions that occur when that limit or its interim steps are breached. The limit is a governance tool. It does not guarantee a hard stop on losses at an exact threshold. It sets a trigger at which risk is reduced or suspended to avoid compounding further losses under unfavorable conditions.

Drawdown control can be defined at several levels:

- Absolute equity drawdown. A cap on peak-to-trough loss as a percentage of the high-water mark. For example, a rule may prescribe progressive risk cuts at 5 percent and 10 percent drawdowns, with a trading suspension at 15 percent.

- Rolling-window drawdown. Limits referenced to drawdown within a fixed horizon, such as month-to-date or quarter-to-date, to avoid long-memory effects creating permanent throttles.

- Strategy-specific drawdown. Limits measured per strategy silo to contain damage from a single sleeve, in addition to a portfolio-level limit that governs aggregate risk.

- Investor or mandate drawdown. External capital often arrives with formal loss limits embedded in offering documents or investment policy statements. These may impose more stringent thresholds than internal limits.

The associated actions can be binary or graduated. Binary rules suspend trading entirely once a threshold is breached. Graduated rules throttle exposure in steps as drawdown deepens. Many practitioners prefer graduated controls to avoid an abrupt stop that forces liquidation at inopportune times. The core idea is the same. As realized losses accumulate, the process earns a smaller risk budget until it revalidates or recovers.

Why Drawdown Limits Are Critical to Capital Preservation

Capital preservation has three dimensions. Financial survival, operational survival, and psychological survival. Limits of drawdown control support each dimension in distinct ways.

Financial survival. Large losses require disproportionately large gains to recover. A formal limit restricts the downside before the recovery task becomes prohibitive. It also prevents undiscounted compounding of independent risks that happen to be negatively aligned at the same time.

Operational survival. Many trading businesses depend on external capital, prime brokerage relationships, and risk committees. Persistent or deep drawdowns can trigger redemptions, margin changes, and forced deleveraging. A transparent limit with precommitted actions helps maintain credibility with stakeholders who require evidence of disciplined risk control.

Psychological survival. Drawdowns strain judgment. Under pressure, traders are prone to increase risk to recover quickly or to abandon processes at the worst moment. A drawdown limit reduces decision load in stressful conditions by replacing improvisation with a pre-specified playbook. That playbook lowers the risk of large, irreversible errors.

Measurement Choices That Shape Control

Drawdown control depends on how losses are measured, aggregated, and monitored. Several methodological choices matter.

- Mark-to-market versus realized P&L. A mark-to-market approach recognizes losses as soon as prices move. A realized approach triggers actions when positions are closed. Mark-to-market is more responsive but can be noisier. Realized thresholds are stickier but risk delayed responses.

- Closed equity versus open equity. Some processes monitor drawdown on closed equity only. Others use total equity, including open positions. Monitoring total equity captures current risk more completely, especially for leveraged or option positions where open risk can change rapidly.

- Frequency of monitoring. Intraday, daily, or weekly monitoring can produce different trigger patterns. Intraday controls may mitigate runaway losses but can introduce a large number of small interventions. Daily controls consolidate noise but can miss rapid moves within a session.

- Netting rules across strategies. A portfolio that nets winners and losers may mask a failing sleeve. Silos detect local failure early but may overreact to noise. Many programs pair both. Constrain sleeve-level drawdowns and also control aggregate drawdown to protect the whole.

- Inclusion of fees, financing, and slippage. Limits should reference net P&L including transaction costs, funding, borrow costs, and known slippage effects. Excluding these costs understates true drawdown and creates a false sense of safety.

Whichever choices are adopted, they should be documented in a rulebook and implemented consistently. Inconsistent measurement undercuts the purpose of a limit by creating room for ad hoc reinterpretation when conditions are difficult.

How Drawdown Limits Operate in Practice

Implementation varies across trading styles, but common patterns exist.

Single strategy with staged risk reduction

Consider a directional futures strategy that sizes positions to a fixed percentage of equity risk per trade. The risk team specifies three drawdown tiers. At a shallow drawdown, reduce risk by a small fraction. At a moderate drawdown, halve risk. At a deeper drawdown, halt new entries and allow only risk-reducing trades. The throttle remains in place until the equity curve recovers a portion of the loss or until an independent review revalidates the process. The goal is to slow the rate of capital loss while preserving the option to resume when conditions improve.

Portfolio with correlated sleeves

Suppose a multi-asset portfolio runs momentum in equities, carry in currencies, and trend in rates. In placid periods these sleeves appear diversified. In a regime shift they can co-move as risk-off pressure rises. A portfolio-level drawdown limit captures the combined tail even if each sleeve stays within its local threshold. When the aggregate limit trips, the risk budget is cut across the book to reflect the hidden correlation that has emerged.

Intraday trader with a daily loss cap

For high-turnover intraday processes, it is common to define a daily limit that triggers a stop for the rest of the session. This contains behavioral escalation after an early string of losses. It also limits the chance that a single volatile session inflicts disproportionate damage. Weekly or monthly controls can coexist with the daily cap to govern multi-day accumulation of losses.

Numerical Illustrations

Examples help clarify magnitudes without implying recommendations. Imagine an account with a peak equity of 1,000,000. The policy specifies a progressive throttle. At a 5 percent drawdown, reduce risk by one third. At 10 percent, reduce by one half. At 15 percent, cease initiating new risk until recovery of at least half the drawdown or until a revalidation test is passed.

If equity declines to 950,000, the first step cuts exposure. Suppose the equity curve then continues to 900,000. The second step halves exposure again. At 850,000, new positions are suspended. If the market reverses and existing positions recover equity to 925,000, the program can resume at a reduced rate while remaining under a more conservative cap until it surpasses 950,000. If instead losses deepen abruptly to 800,000 because of a gap move, the policy has still served its purpose. It did not prevent the gap. It limited the opportunity for subsequent compounding by suspending new risk and by imposing a lower throttle on remaining exposure.

Now consider portfolio aggregation. Suppose three sleeves each allocate 300,000 of risk capital within the same 1,000,000 account. Each sleeve has a 7 percent local drawdown limit. The portfolio has a 12 percent aggregate limit. A correlated shock hits, and all three sleeves draw down 6 percent simultaneously. Each sleeve remains under its 7 percent limit, yet the portfolio is down 18 percent relative to peak. The aggregate limit triggers a portfolio-wide response. This example shows why portfolio limits are essential. Local limits do not always prevent large combined losses when correlations rise.

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Limits of drawdown control are powerful, but they are sometimes misunderstood or misused. Several issues recur.

- Myth of guaranteed containment. A limit is not a price stop. It does not guarantee that losses will halt at exactly the prescribed level. Gaps, illiquidity, and slippage can push through any administrative threshold. The limit governs behavior after the breach.

- Setting limits too tight. If thresholds are set close to normal noise, routine fluctuations will repeatedly throttle or halt trading. This raises transaction costs, increases whipsaw, and may prevent the process from expressing its edge. The result is an unintended performance tax.

- Setting limits too loose. If thresholds are far beyond realistic recovery capacity, the limit will rarely bind until losses are already unacceptable. This undermines the purpose of capital preservation and can threaten operational survival if external stakeholders require tighter controls.

- Ignoring correlation and concentration. Per-asset or per-sleeve limits can create a false sense of security when positions share risk factors. Stress events often increase correlation. Drawdown limits must be considered at the portfolio level with a view to factor exposures.

- Overfitting to the backtest. Tuning limits to the historical worst case or to the ninety-ninth percentile of simulated paths can produce deceptively precise numbers that do not generalize. Realized drawdowns can exceed backtest extremes once the process is deployed.

- Discretionary override under stress. The temptation to suspend the policy after a breach is strong. Ad hoc exceptions erode the credibility of the rule and can lead to even larger losses. Changes to limits require a formal change process that is separate from day-to-day trading.

- Neglecting costs and funding. Funding rates, borrow costs, and slippage often increase in stress periods, deepening drawdowns beyond model expectations. Limits that ignore these elements underestimate risk.

- One-size-fits-all limits. Strategies with nonlinear payoffs, such as options, can generate drawdowns that accelerate with volatility. Applying the same threshold to linear and convex exposures misses this features.

Calibrating Limits in a Framework

Calibrating drawdown limits is a design exercise. It links statistical properties of returns, the business need for survivability, and the tolerance of investors or principals. Several components help build a coherent framework without prescribing specific numbers.

- Map drawdown to recovery capacity. Analyze the return distribution and turnover profile to estimate realistic recovery rates after a loss. A high-turnover strategy with frequent signals may recover faster than a low-turnover strategy. The limit should be compatible with the feasible recovery horizon.

- Assess the frequency of expected breaches. Historical data, stress tests, and simulation can estimate how often a limit would have triggered. A rule that triggers monthly for a slow-moving strategy is likely too tight. A rule that never triggers in rich historical datasets may be too loose.

- Consider regime dependence. Volatility regimes, liquidity conditions, and structural breaks change drawdown behavior. A single static threshold may not be appropriate across regimes. Some programs adapt limits to volatility or spreads within a defined range and with guardrails.

- Integrate with position sizing. Sizing rules and drawdown limits interact. A program that scales positions to volatility may already reduce risk during high-volatility periods. The drawdown limit should complement, not duplicate, the sizing method.

- Respect external constraints. If capital providers define a maximum loss tolerance, internal limits should be tighter to provide a buffer. This guards against timing differences between internal measurement and external reporting.

Scenario analysis is a practical tool. Construct stylized shocks, such as gaps equal to several times the daily average true range, and examine the implied equity impact. Add realistic slippage and funding changes. If the resulting equity path crosses the proposed limit too often or concentrates breaches in plausible regimes, revisit the design.

Governance, Monitoring, and Reset Rules

A drawdown limit is only effective if it is monitored reliably and followed consistently. Governance turns a number into a process.

- Documentation. The policy should define the metric, data source, frequency, trigger levels, and specific actions. It should explain how to handle data errors, stale marks, and holidays so that ambiguity does not surface at the worst time.

- Automation with oversight. Automated alerts and throttles reduce the risk of delayed execution under stress. Human oversight audits the triggers and approves any actions that require discretion within the policy.

- Reset criteria. After a breach, specify when and how risk capacity is restored. Time-based resets, performance-based resets, or revalidation by an independent review are common approaches. Abrupt full resets without analysis risk repeating the same error.

- Change control. If limits are modified, record the rationale, data, and decision authority. Separating change control from live trading sessions reduces the influence of recency bias.

Edge Cases and Special Considerations

Different instruments and styles create distinctive challenges for drawdown control.

- Options and other convex exposures. Delta, gamma, and vega can shift rapidly with price and volatility changes. Mark-to-market drawdowns can accelerate even if the underlying moves modestly. Limits for options portfolios often include additional constraints on Greeks or scenario losses to capture nonlinear risk.

- Funding and carry strategies. Strategies that earn carry or financing income can experience long periods of smooth returns followed by sharp drawdowns. Limits calibrated to typical volatility may be too loose for tails, and too tight during normal times if made reactive. Many practitioners pair drawdown limits with tail risk scenario caps for these strategies.

- Illiquid or episodic markets. In thin markets, marks can be stale and gaps large. A daily measurement may understate intraday risk, while an intraday measurement may show jumps that cannot be traded. Here, drawdown control must be paired with conservative assumptions about exit prices and with position size limits that anticipate poor liquidity.

- Event risk and trading halts. Exchange halts, circuit breakers, and limit-down events constrain the ability to respond. Drawdown limits cannot override market microstructure. Predefined exposure caps ahead of known events are often used in addition to drawdown rules.

Distinguishing Drawdown Limits from Other Controls

Drawdown limits complement but do not replace other risk tools.

- Stop-loss orders. Stops manage risk at the position level. Drawdown limits manage risk at the process or portfolio level. Both can fail in gaps, but the drawdown limit governs whether new risk is added after damage accumulates.

- Volatility targeting. Vol targeting scales exposure based on estimated variance. It can reduce losses during high-volatility regimes. Drawdown limits attend to cumulative equity damage regardless of the source.

- Capital allocation limits. Exposure caps, concentration limits, and leverage constraints bound potential losses ex ante. Drawdown limits respond to what has already happened in the equity path.

Behavioral Effects and Communication

Drawdown limits have a behavioral purpose. They reduce discretion when emotions run high. For teams, clear limits prevent internal debates from escalating during stress. For external stakeholders, transparent rules improve communication and trust. Reporting should show current drawdown, recent triggers, and whether the program is operating at reduced capacity. Clarity about the reset process reduces uncertainty and speculation.

Practical Walkthrough

Consider a quantitative strategy with moderate turnover that trades liquid futures. The team studies historical performance and stress tests. They find that in quiet regimes the strategy rarely exceeds a 6 percent drawdown, while regime shifts can produce 12 to 18 percent drawdowns before recovery. They also note that correlation with a second sleeve rises during selloffs. The policy they design commits to the following constructs.

- Use total equity, including open positions, marked daily from independent prices.

- Monitor both sleeve-level and portfolio-level drawdowns, with the portfolio limit tighter than any external mandate.

- Apply a three-step throttle. Risk capacity decreases at two shallow thresholds and halts new risk at a deeper threshold.

- Define a reset process that requires either recovery of half the drawdown or independent revalidation after a minimum cooling-off period.

- Embed scenario triggers for large gap risks that can override the normal steps if a single-session loss exceeds a defined shock size.

In a live episode, the portfolio hits the first step after a cluster of small losses. The throttle cuts exposure and the daily variance of P&L falls. A week later, a macro event pushes the equity curve further down, triggering the second step. The team reduces positions accordingly and suspends new risk in one sleeve that shows the poorest performance relative to expectation. A subsequent rebound begins to repair equity. The throttle remains until the portfolio clears the reset condition. Throughout, the team communicates the state of play in risk reports that show the high-water mark, current drawdown, which throttle is active, and the expected criteria for resetting. The process converts a stressful episode into a governed sequence with clear boundaries.

What Limits of Drawdown Control Cannot Do

Drawdown limits are necessary, but they are not sufficient. They cannot substitute for a sound strategy. They cannot override market microstructure that prevents exits at desired prices. They cannot ensure that risk and return will be attractive after the limit is triggered. What they can do is bound the maximum loss that the process is likely to experience before being forced to stop adding risk. That boundary supports long-term survivability by keeping losses within a range that is potentially recoverable given the characteristics of the strategy.

Closing Perspective

Limits of drawdown control translate a principle of prudence into operational rules. They recognize that compounding requires survival, that recovery from large losses is mathematically demanding, and that human judgment is least reliable under pressure. When designed with care, calibrated to the process, integrated with other controls, and executed consistently, drawdown limits help protect the scarce resource that underlies every trading endeavor. Capital and the time needed for it to compound.

Key Takeaways

- Limits of drawdown control set predefined thresholds on equity loss and specify actions that throttle or suspend risk to protect capital.

- They address path dependency by responding to cumulative losses rather than relying solely on average risk metrics.

- Measurement choices, including mark-to-market conventions, monitoring frequency, and aggregation rules, shape how and when limits trigger.

- Common pitfalls include assuming limits guarantee containment, setting thresholds too tight or too loose, and ignoring correlation and costs.

- Well-governed drawdown limits complement position-level stops and volatility targeting, supporting financial, operational, and psychological survival.