Exposure is the bridge between a portfolio’s positions and its risk. Many losses that appear sudden are the product of exposure decisions that accrued quietly, often masked by routine market conditions or misleading statistics. Common exposure mistakes arise when positions that seem independent share the same drivers, when correlation is misread or assumed to be constant, or when sizing is based on notional values rather than economic risk. Understanding and avoiding these errors is central to capital preservation and long-term survivability.

Defining Common Exposure Mistakes

Common exposure mistakes are errors that cause a portfolio to carry more risk than intended because exposures overlap or are mismeasured. The core mechanisms include:

- Hidden correlation, where positions share the same factor drivers even though they look different by ticker, asset class, or region.

- Mis-specified sizing, where notional amounts, leverage multiples, or share counts substitute for risk-adjusted sizing.

- False diversification, where more lines in the portfolio create an illusion of safety without reducing common factor exposure.

- Instability of relationships, where historical correlations shift across regimes, especially during stress.

- Look-through failures, where ETFs, structured products, or derivatives embed exposures that are not recognized at the portfolio level.

These mistakes are not rare. They reflect the complexity of financial markets and the tendency to rely on surface differences among positions rather than on the economic forces that move them.

Why the Concept Is Critical to Risk Control

Risk management protects the ability to stay in the game. Exposure mistakes threaten this by clustering risk unintentionally. During benign periods, offsetting moves may obscure the problem. When volatility rises, hidden linkages can align, transforming small estimation errors into large drawdowns.

Several properties make exposure discipline essential:

- Correlation is conditional. Relationships between assets tend to strengthen during stress. Portfolios that looked diversified on calm days can behave like concentrated trades under pressure.

- Losses scale nonlinearly. As exposures co-move, variance compounds. A set of independent 2 percent risks does not behave like a single 10 percent risk, but correlated losses can approach that outcome.

- Liquidity interacts with exposure. When many investors share a crowded exposure, exits can widen spreads and magnify impact costs. This is especially relevant for leveraged or derivative-based positions.

- Survivability requires margin efficiency. Unintended overlap can consume margin or capital buffers in a correlated selloff, constraining flexibility when it is most needed.

Exposure and Correlation: Foundations

Exposure can be described along several dimensions. Each dimension offers a different window into how a portfolio might behave:

- Directional exposure. Sensitivity to the price level of an asset or index, such as beta to an equity market or delta to an underlying in options.

- Factor exposure. Sensitivity to systematic drivers like value, momentum, size, quality, interest rate duration, inflation, or commodity risk premia.

- Cross-asset exposure. Relationships between equities, rates, credit, FX, and commodities, which often tighten during stress events.

- Volatility and convexity exposure. Sensitivity to changes in volatility, skew, and curvature through options, structured notes, or callable instruments.

- Basis and spread exposure. Dependence on the relationship between two prices rather than on a single price level. Examples include futures basis, ETF tracking difference, or relative-value spreads.

Correlation summarizes how returns move together, but it is only a summary statistic. It is sample dependent, time varying, and often nonlinear. A correlation of zero does not mean independence, and negative correlation at small moves can flip in large moves. For risk control, it is better to interpret correlation as a fragile estimate rather than as a law of motion.

Anatomy of Common Exposure Mistakes

1. Confusing Notional Size with Economic Risk

Equal notional amounts can have very different risk. A 100,000 notional in a low volatility government bond future does not carry the same risk as 100,000 in a small-cap equity. Similarly, an options position with small premium but large gamma can dwarf the risk of a fully paid cash position. When sizing is based on cash or notional value, the portfolio can accumulate hidden concentration in high volatility assets.

2. Double Counting Through Thematic Overlap

Holding a technology index fund, several large-cap technology stocks, and a semiconductor ETF can feel diversified by issuer count. In practice, these positions load on overlapping growth, profitability, and interest-rate sensitivity factors. Earnings revisions or a rates shock can drive simultaneous losses across all lines.

3. Misreading Hedging Relationships

Hedges depend on the match between what is owned and what is used to offset. A producer that is long crude oil price risk and hedges with an energy equity ETF is taking on equity and balance sheet risk in addition to commodity exposure. A bond portfolio hedged with equity index puts gains equity downside protection but may still carry significant interest rate convexity. Basis risk, liquidity, and timing can convert a partial hedge into additional risk.

4. Assuming Correlations Are Stable

Correlations are regime specific. Equity and duration often move in opposite directions in disinflationary slowdowns, yet can move together during inflation shocks. A portfolio constructed on a five-year correlation matrix may be exposed to a different relationship in the next quarter. Relying on historical averages without considering macro context is a common source of surprise.

5. Ignoring Currency and Funding Exposures

Foreign assets introduce currency risk even when the underlying is stable. Long an overseas equity with unhedged currency exposure can behave like a currency trade during a sharp FX move. In derivatives, funding and margin terms create exposure to interest rates, collateral returns, and roll costs. These components can dominate returns in quiet markets.

6. Crowding and Liquidity Mismatch

Portfolios can share exposures with the broader market. When many participants hold similar trades, normal liquidity assumptions break down at the same time for everyone. The effective exposure grows because price impact rises exactly when participants try to de-risk. ETFs and derivatives that track less liquid underlyings can exhibit additional slippage under stress.

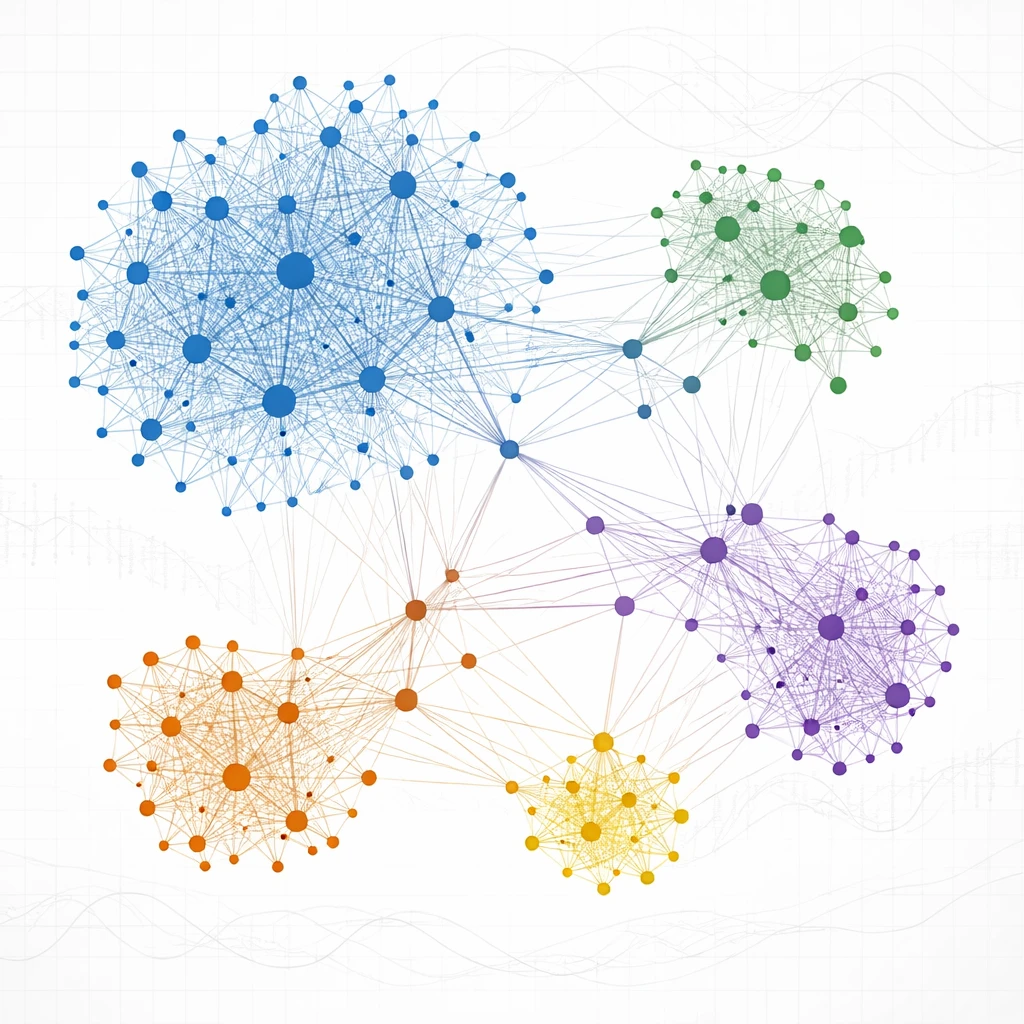

7. Overreliance on Pairwise Correlations

Even with low pairwise correlations, portfolios can be exposed to a common factor. Three assets can each show low correlation with the others and still load on the same macro driver, such as the US dollar or real rates. Factor models help reveal this, but even factor sensitivities change through time.

8. Treating Options as Risk-Free Hedges

Options redistribute risk rather than remove it. Long options reduce downside conditional on premium paid, but they introduce theta, vega, and liquidity considerations. Short options collect premium but add short volatility and jump risk. Position sets that include covered calls, short puts, or ratio spreads can increase exposure to gap moves even though they appear yield enhancing in calm markets.

9. Overlapping Time Horizons

Exposure is not only about what positions are held, but when risk is concentrated. Clustering earnings releases, policy announcements, or roll dates can create time-based exposure. Several small positions can jointly face the same catalyst window and behave like a single large bet on that event’s outcome.

10. Neglecting Look-Through for Structured and Index Products

Index funds, sector ETFs, risk parity sleeves, and structured notes embed exposures that need look-through analysis. A portfolio that holds an industrials ETF and several large industrial names might unknowingly exceed sector limits. Commodity notes often embed collateral and financing returns that change the effective exposure relative to spot prices.

How These Errors Appear in Real Trading Scenarios

Case A: The Apparent Hedge That Raises Risk

Consider a trader long a basket of growth equities, concerned about macro weakness. They add a short position in a cyclical sector to hedge. Historical correlations suggest partial offset. A rates shock then arrives. Growth and cyclicals both decline as discount rates rise, and the correlation between them moves toward one. The hedge does not compensate, and the portfolio experiences a larger drawdown than anticipated. The exposure mistake was assuming the historical cross-correlation was stable across a different macro driver.

Case B: Basis Risk in Futures and ETF Substitutions

A portfolio holds physical commodities via an ETF that tracks front-month futures. To reduce inventory risk, the manager replaces part of the position with a deferred futures contract. During a supply shock, the curve flips from contango to backwardation. The ETF and deferred futures diverge, and the intended alignment fails. The combined position now depends on the basis between two parts of the curve, a risk that was not measured when the switch was made.

Case C: Duration Hidden in Equities

Bank equities and short positions in government bond futures may appear to offset rate risk. In a rapid fall in yields driven by growth fears, bond futures rise, and bank equities decline as credit concerns grow. The short bond hedge loses, and the equity losses compound the move. Both legs were exposed to the same macro shock, but through different channels. Correlation was not constant, and the economic exposure was not symmetric.

Case D: Currency as the Primary Driver

An investor buys shares in a high-quality overseas firm. The thesis is company specific, but the domestic currency strengthens sharply. The equity’s local return is positive, yet the portfolio’s base currency return is negative. The largest driver of P&L is the currency translation. The exposure mistake was treating the asset as a pure equity when currency risk dominated outcomes over the holding period.

Case E: Options and the Illusion of Limited Risk

A covered call program on a concentrated equity position appears to moderate risk by collecting premium. The underlying then gaps lower on an adverse announcement. The collected premium does little to offset the move, and the investor is still long the stock’s jump risk. Alternatively, a short put strategy that generated steady income for months faces a volatility spike and gap down, revealing the embedded short convexity exposure.

Diagnosing and Measuring Exposure

Several diagnostic practices are widely used in risk management to reveal where exposure mistakes might arise. They are conceptual tools rather than prescriptive rules:

- Gross, net, and factor-adjusted views. Gross exposure sums the absolute size of long and short positions, net exposure subtracts shorts from longs, and factor-adjusted exposure translates positions into common risk drivers, such as beta to a market index or duration in fixed income.

- Volatility scaling. Position sizes are expressed in volatility units so that each contributes comparably to expected variance. This highlights when a small notional in a volatile asset contributes more risk than a large notional in a stable asset.

- Scenario analysis. Positions are mapped to shocks that represent plausible regimes, such as a rates up 100 basis points move, a growth scare, an oil price spike, or a dollar rally. The goal is to evaluate how relationships might change rather than to rely on average correlations.

- Look-through aggregation. Index products, ETFs, and structured notes are decomposed into their constituents or risk factors. This avoids double counting and reveals concentration that is not obvious from tickers alone.

- Liquidity and crowding checks. Expected participation rates, average daily volumes, and open interest provide context on whether exits would be feasible under stress. The focus is on how price impact increases effective exposure.

- Nonlinearity mapping for options. Greeks across price paths, not just at spot, help identify where convexity concentrates risk. Shocks to implied volatility and skew expose the dependence on vol regimes.

Misconceptions and Pitfalls

“More Positions Equal Diversification”

Adding names that load on the same factor does not reduce risk meaningfully. Ten growth stocks can be less diversified than three positions that span different economic drivers. Diversification is about the independence of exposures, not the count of positions.

“ETFs Eliminate Concentration Risk”

ETFs package exposures efficiently, but their components can still create concentration. Sector and thematic funds can be highly correlated with single names already in the portfolio. During stress, ETF flows can amplify underlying moves.

“Bonds Always Hedge Equities”

In disinflationary recessions, government duration often offsets equity risk. In inflationary shocks, both can sell off together. The sign and magnitude of the correlation depend on the dominant macro regime.

“Negative Correlation Is Reliable”

Correlations migrate toward one under severe stress across many assets that normally trade independently. Designing exposure solely on historical negatives can fail when the shock that matters is different from the one in the data.

“Options Automatically Reduce Risk”

Short premium exposures benefit from calm periods and can suffer large losses on jumps. Long premium exposures reduce downside but can degrade returns through carry. Options reshape the distribution of returns rather than removing exposure outright.

“Currency Exposure Is Secondary”

For internationally diversified portfolios, currency can dominate total return variance over medium horizons. The effect is largest when equity volatility is modest and FX volatility is elevated.

“Historical Correlation Equals Future Correlation”

Correlation is a moving target influenced by policy, inflation dynamics, and market structure. Reliance on long samples can mask current-linkage changes. Short samples can capture noise rather than signal.

Conceptual Controls That Address Exposure Mistakes

Professional risk management emphasizes a few principles designed to reduce the likelihood of exposure errors, without prescribing particular trades:

- Define exposure in risk units. Express positions through volatility, beta, or duration rather than notional alone.

- Diversify across independent drivers. Seek exposure to distinct economic mechanisms instead of many expressions of the same theme.

- Stress for regime shifts. Evaluate how correlations might behave under inflation scares, policy pivots, or liquidity droughts.

- Perform look-through aggregation. Decompose complex instruments to ensure the portfolio view matches the economic exposure.

- Monitor liquidity and crowding. Understand how turnover and market depth can change effective exposure when volatility rises.

These concepts do not guarantee safety. They aim to reduce the chance that exposure surprises will dominate outcomes, particularly during adverse periods when capital preservation is most important.

Long-Term Survivability and Capital Protection

Survivability is a function of avoiding large drawdowns that impair compounding. Exposure mistakes are a common pathway to such drawdowns because they cluster risk inadvertently. By identifying shared drivers, accounting for instability in relationships, and measuring risk in economic terms, portfolios can be constructed with a clearer understanding of how they might behave under strain.

In practice, survivability is linked to flexibility. Portfolios with well-understood exposures tend to preserve optionality during volatile periods. They are less likely to encounter binding margin, capital, or liquidity constraints at the same time that adverse price action arrives. While outcomes can never be fully controlled, avoiding common exposure mistakes can reduce the likelihood of forced decisions and capital impairment.

Extended Examples of Overlap and Hidden Risks

Equity Factor Overlap

A portfolio owns a quality factor ETF, a group of large-cap healthcare companies, and a defensive consumer staples name. Historical beta suggests low market sensitivity. A policy shock changes reimbursement expectations and input costs. Healthcare and staples fall together, and the quality ETF declines as valuation multiples compress. The shared driver was the defensive equity factor’s sensitivity to rates and regulation. Issuer count did not translate into distinct exposures.

Rates and Real Assets

Real estate investment trusts and infrastructure equities can be sensitive to real rates and inflation expectations. A rise in real yields reduces the present value of cash flows, and both sectors can decline together even if cash flows are stable. A commodities sleeve meant to diversify equities might offset the move in some regimes, but can also underperform if the yield increase reflects growth rather than inflation. The direction and magnitude of interactions depend on the macro channel.

Credit and Equity Linkages

High yield credit exposure and cyclical equities can respond similarly to growth shocks. A portfolio holding both may think of them as independent because one is a bond and the other is a stock. During a growth scare, spreads widen and cyclical equities sell off in tandem, revealing the common driver.

FX and Emerging Markets

Local currency sovereign bonds, exporters’ equities, and commodity exporters often share exposure to the global dollar cycle. A dollar rally can pressure all three, even if the drivers appear different when analyzed separately. Overlap is strongest during global risk-off episodes when funding conditions tighten.

Practical Signals That Exposure May Be Misstated

- Unusually smooth P&L followed by abrupt drawdown. Smoothness can reflect hidden short volatility or carry exposures that snap under stress.

- Repeated losses around the same macro events. Concentrated sensitivity to policy decisions or inflation prints indicates a shared driver across lines.

- Large slippage when adjusting positions. Impact costs that exceed expectations suggest crowding and latent liquidity risk.

- Hedge effectiveness decays across regimes. Hedges that worked in one environment and fail in another point to correlation instability.

- Complex products behave unexpectedly. Tracking error in ETFs or structured notes can reveal basis and financing exposures that were not incorporated in the portfolio view.

Building Better Questions About Exposure

Effective risk control often begins with precise questions:

- What are the main economic drivers of this position, and how do they overlap with others already held?

- How would this portfolio behave if the dominant regime changed from disinflation to inflation, or from stable liquidity to scarcity?

- Which positions are short volatility or short liquidity implicitly, and how large are they in risk units rather than notional?

- Where does basis risk enter, and what are the plausible ranges for that basis under stress?

- How much of the portfolio’s variance is explained by a small number of factors, and is that proportion intentional?

Conclusion

Common exposure mistakes originate in the gap between what is held and how it behaves under change. They involve misunderstanding of correlation, failure to account for shared drivers, and reliance on notional sizing that ignores volatility and convexity. By framing positions in economic terms, confronting the instability of relationships, and examining the portfolio through multiple lenses, investors can reduce the likelihood that hidden overlap will undermine capital during adverse periods. Protection of trading capital and long-term survivability depend less on predicting outcomes and more on understanding how exposure aggregates when conditions shift.

Key Takeaways

- Exposure mistakes arise from hidden correlation, mismeasured risk, and false diversification, not simply from large positions.

- Correlation is conditional and unstable, so historical relationships may fail when regimes change.

- Economic sizing using volatility, beta, duration, and convexity reveals concentration that notional sizing misses.

- Look-through analysis of ETFs, derivatives, and structured products is essential to avoid double counting and basis risk.

- Protecting capital and survivability relies on understanding aggregate exposure more than on predicting market direction.