Diversification is a foundational idea in portfolio construction. It spreads exposure across assets or strategies so that independent gains and losses partially offset each other. The effect is real, measurable, and central to modern portfolio theory. Yet diversification is not a free insurance policy, nor is it boundless. The concept of limits of diversification addresses where and why the benefits taper, and under what conditions portfolios that appear well diversified still experience concentrated risk.

What Limits of Diversification Means

The idea refers to the diminishing ability of additional holdings to reduce risk when the remaining risk is driven by common factors. Adding one more stock to a handful of names can sharply reduce idiosyncratic risk. Adding a hundredth stock to an already broad equity basket does not. At the portfolio level, combining different asset classes can reduce volatility because they are not perfectly correlated. However, correlations are not fixed, economic shocks can be pervasive, and practical frictions can erode the theoretical gains. Limits of diversification are the set of structural, statistical, and operational reasons why spreading exposures cannot eliminate risk and may only trim it by less than expected.

What Diversification Can and Cannot Do

Diversification works by offsetting independent risks. If two investments are uncorrelated, their combined variance is lower than the average of the individual variances. The more independent return streams you combine, the more idiosyncratic risk cancels. This logic underpins index funds, multi-asset portfolios, and factor-mix portfolios.

What diversification cannot do is remove systematic risk. Market-wide shocks, policy shifts, liquidity crunches, and inflation surprises affect many assets simultaneously. When the remaining risk in a portfolio is dominated by such common forces, adding more line items does not materially change the aggregate outcome. Diversification is also less effective when relationships between assets change precisely when they are most needed to be stable.

Correlation Is Not Constant

Textbook examples often assume stable correlations. Real markets display time-varying, state-dependent, and asymmetric relationships. During benign periods, assets may appear weakly correlated. During stress, correlations can rise quickly as investors de-risk, funding conditions tighten, and risk premia reprice together.

Two related features are important:

- Tail dependence. Even if average correlation is low, the likelihood of co-movement in extreme outcomes can be high. Many assets that seem independent in normal times lose independence in the tails.

- Regime shifts. Inflation regimes, monetary policy changes, and credit cycles can permanently alter cross-asset relationships. A diversifier in one regime can become a fellow traveler in another.

These features bind the ceiling on diversification benefits. A portfolio constructed from long histories of benign correlations can underdeliver when the correlation structure shifts.

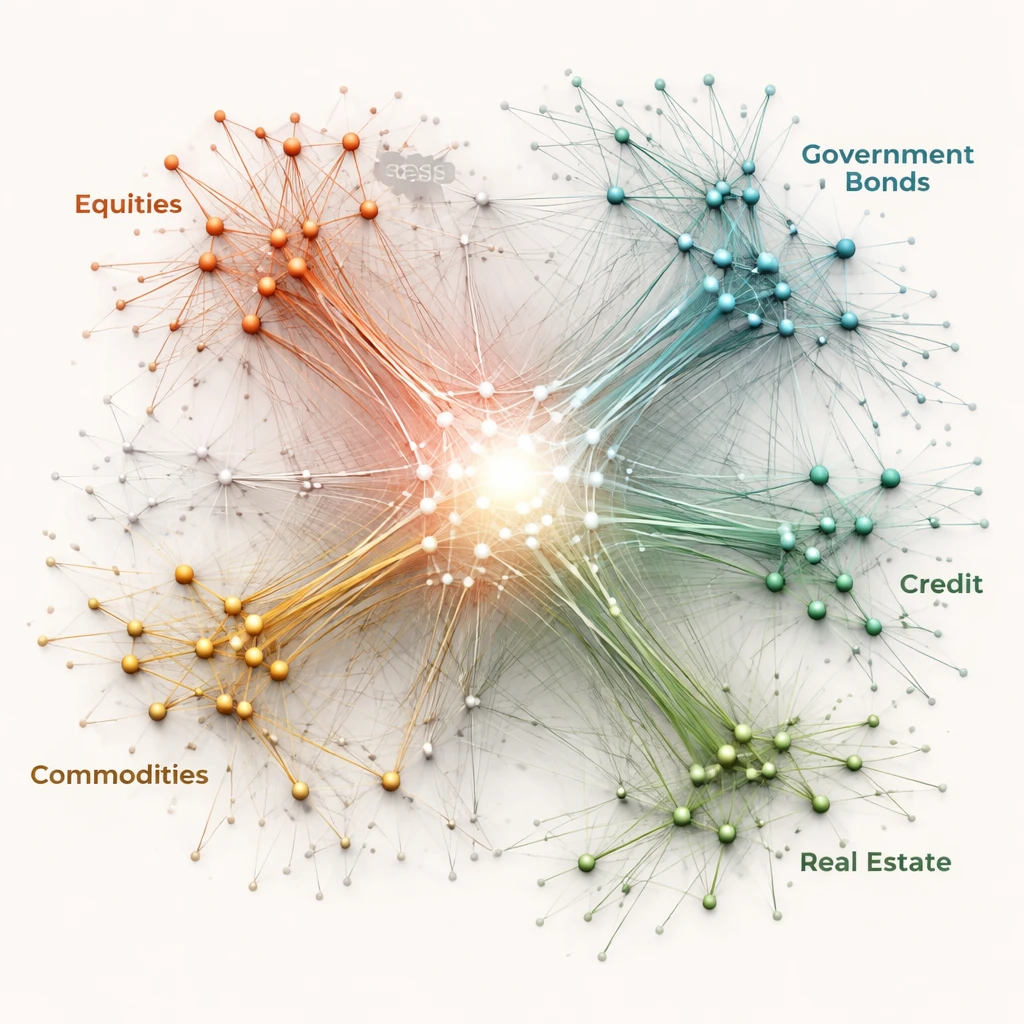

Hidden Common Factors

Another source of limits arises from hidden or underappreciated common exposures. Assets can move together because they share sensitivity to macro variables or investor behavior. Thinking in factors provides a clearer frame than thinking in tickers.

- Equity beta. Many assets embed equity-like risk. High yield bonds, listed real estate, and parts of private equity often load positively on equity market movements, especially during downturns.

- Duration. Interest rate sensitivity links government bonds, investment-grade credit, and even some equity sectors. Shifts in yield curves can affect them in tandem.

- Inflation and commodities. Energy, materials, and inflation-linked instruments share exposure to price level shocks. Their diversification benefit depends on the inflation regime and supply dynamics.

- Liquidity and funding. A cross-cutting factor. When liquidity evaporates, bid-ask spreads widen and risk premiums jump together. Strategies that require leverage or financing can co-move due to margin channels, regardless of asset class labels.

From a statistical angle, the limits show up when a small number of principal components explain most portfolio variance. If the first component accounts for a large fraction of total risk, there is less room for diversification to achieve further reductions.

Asset-Class Examples in Context

Consider a multi-asset portfolio that holds global equities, investment-grade bonds, high yield bonds, listed real estate, commodities, and cash. In a typical low-inflation, stable-growth environment, bonds may offset equity drawdowns as yields fall and bond prices rise. Commodities may be only loosely related to either. The resulting volatility can be materially lower than for any single sleeve.

Now consider three different contexts:

- 2008 global financial crisis. Equity markets sold off sharply, credit spreads widened, and listed real estate drew down, reflecting their shared sensitivity to growth and leverage. Government bonds in developed markets rallied, providing offset, but many other supposed diversifiers co-moved downward as liquidity dried up. The diversification ceiling was defined by a common deleveraging shock.

- 2020 pandemic shock. During the acute phase, correlations converged as investors rushed to cash. Policy interventions later changed dynamics, but the initial window illustrates how even unrelated assets can synchronize under stress.

- 2022 inflation shock. Equities and high-quality bonds fell together as rising inflation and interest rates pressured multiples and bond prices. A historical negative correlation between stocks and bonds can flip in an inflationary regime, revealing a limit to diversification that had been concealed by a long disinflationary period.

These episodes underscore that diversification benefits depend on the shock type. If a shock loads on both growth and inflation, standard pairings can move together and offer less protection.

Diminishing Marginal Benefits

Within a single asset class, the variance reduction from adding names falls rapidly. For equities, moving from one stock to twenty can remove much of the idiosyncratic risk. Moving from fifty to five hundred reduces risk far less, because most of what remains is market and sector exposure. A similar tapering applies when layering more asset classes that share macro drivers. The first truly independent sleeve contributes more to risk reduction than the tenth variant of an already represented factor.

Diminishing benefits also reflect finite opportunity sets. There are only so many distinct, tradable, and scalable risk premia available at a given time. Chasing ever finer slices can lead to complexity without commensurate risk reduction.

Implementation Frictions That Erode Diversification

Theoretical gains assume costless, continuous, and instantaneous rebalancing among perfectly liquid instruments. Real portfolios contend with frictions that introduce limits:

- Transaction costs and taxes. Frequent rebalancing to maintain target weights can create drag. In taxable accounts, realizing gains to rebalance may reduce the long-term net benefit.

- Liquidity constraints. Some assets can be costly to enter or exit at scale. In stress periods, liquidity can vanish and prices can gap, making desired diversification hard to monetize.

- Capacity and market impact. Large allocations can move prices or force the use of proxies that carry basis risk relative to the intended exposure.

- Operational and governance limits. Complex portfolios require oversight, valuation frameworks, and counterparty management. Execution constraints and delayed decision cycles can prevent timely rebalancing, which weakens the realized effect.

Because frictions can be correlated with stress, the very times diversification is most needed are when costs to maintain it are highest.

Over-Diversification and Complexity Risk

Another limit is qualitative. A portfolio can become so diffuse that no position is large enough to matter, yet the aggregate still carries common factor risk. This can resemble closet indexing or an overly complex structure that is hard to monitor. Over-diversification can also dilute any source of skill, if present, by spreading capital across too many similar opportunities.

Complexity introduces governance risk. Misunderstood instruments, overlapping exposures, or opaque vehicles can leave decision-makers unsure of what the portfolio truly holds. This uncertainty can prompt procyclical behavior during stress, which undermines long-term risk control.

Estimation Error and Model Risk

Portfolio construction relies on estimates of expected returns, volatilities, and correlations. These parameters are noisy, especially over short samples or during structural change. Optimizers can overfit to noise and recommend extreme weights that look diversified on paper but are fragile in practice. The gap between ex ante and ex post diversification can be large when parameter uncertainty is ignored.

Two statistical issues are central:

- Sampling variability. With many assets and limited history, covariance matrices are poorly conditioned. Small perturbations can swing optimal weights materially.

- Structural breaks. Past behavior may not predict future relationships when policy regimes, inflation dynamics, or market structure change. What once diversified may cease to do so.

Recognizing these risks frames another limit. Even if true diversification potential exists, the ability to identify and size it accurately is constrained by data and modeling limits.

Tail Risk, Contagion, and Funding Channels

Financial systems transmit shocks through balance sheets. When market participants face margin calls or redemptions, they often sell what is liquid, not what they prefer to sell. This behavior raises co-movement across assets that share investors or financing channels. As a result, tail events can generate correlation spikes that breach theoretical diversification walls.

Contagion can also propagate through collateral and risk management rules. If volatility rises, risk budgets shrink mechanically, triggering de-risking. Such procyclical flows can force assets to move together even when fundamentals differ, which creates practical limits to diversification during crises.

Currency and Geographic Diversification

International exposure is often presented as a source of diversification because economies and policy cycles differ. There are genuine benefits, yet global trade linkages, synchronized monetary policies, and multinational business models cause cross-border correlations to rise at times. Currency adds another layer. Unhedged foreign assets introduce exchange rate risk that can dominate local asset dynamics over shorter windows. Hedging decisions transform risk rather than remove it. The final outcome is that geographic spread helps, but its effect is bounded by global integration and currency behavior.

Nonlinear Payoffs and Basis Risk

Portfolios that include derivatives, structured notes, or options introduce nonlinear responses to market moves. Nonlinear instruments can diversify small moves but concentrate risk around strikes or path-dependent triggers. The intended risk reduction can evaporate if the realized path differs from the assumption. Similarly, using proxies to access an exposure can create basis risk. If the hedge or index does not track the intended risk perfectly, offsets may fail when needed, which is another practical limit.

Rebalancing, Diversification Return, and Their Limits

Systematic rebalancing among volatile but imperfectly correlated assets can generate a rebalancing premium by selling partial winners and adding to partial losers. This effect relies on mean reversion, volatility, and imperfect correlation. It has limits. High transaction costs, persistent trends, or correlation spikes can reduce or reverse the benefit. Moreover, rebalancing a diversified portfolio during stress may be constrained by liquidity or governance, which again points to the practical ceiling on realized diversification gains.

Applying the Concept at the Portfolio Level

At the strategic level, portfolio construction involves deciding which independent sources of risk to include, how to size them relative to long-term objectives, and how to acknowledge the limits of diversification in governance and monitoring. The concept applies in the following ways:

- Variance attribution. Decompose total portfolio risk into contributions by asset class and factor. If a small number of components explain most of the variance, diversification is bounded by those exposures.

- Stress alignment. Map holdings to historical and hypothetical scenarios. If many holdings lose value under the same shock, the diversification ceiling is low with respect to that scenario.

- Liquidity tiers. Recognize that some sleeves are not available as shock absorbers on short notice. Long-horizon diversifiers can still be valuable, but their contribution is time-scale dependent.

- Governance fit. Align complexity with oversight capacity. The benefit of adding another sleeve decreases if it creates process risk that overwhelms its statistical diversification contribution.

The point is to view diversification not as a checklist of asset categories but as a set of independent and durable risk drivers, weighed against the costs and constraints of implementation.

Why Limits of Diversification Matter for Long-Horizon Planning

Long-term investors focus on compounding, drawdown management, and meeting funding needs over many cycles. Limits of diversification inform these aims in several ways.

- Path risk and sequence risk. Even if long-run averages look favorable, the path can include deep drawdowns that impair spending power or breach constraints. If diversification weakens during stress, sequence risk rises.

- Funding and liability alignment. Institutions with liabilities tied to inflation, wages, or interest rates face concentrated risk if the asset side shares the same drivers. Understanding limits helps identify where asset-liability interactions reduce diversification.

- Capital allocation under uncertainty. Because parameters drift and correlations can change, long-horizon planning benefits from ranges rather than point expectations. Recognizing limits reduces overconfidence in precision and guards against brittle designs.

- Resilience versus complexity. There is a trade-off between adding sleeves to chase small marginal gains and retaining a design that can be governed, rebalanced, and understood. Acknowledging limits steers attention to resilience rather than exhaustively enumerating holdings.

Illustrative Portfolio Context

Consider a hypothetical diversified policy mix that includes global equities, sovereign bonds from developed markets, inflation-linked bonds, listed real estate, commodities, and a cash buffer. Over a long historical window, such a mix displayed lower volatility than equities alone and experienced smaller peak-to-trough drawdowns. The dispersion of returns across components provided rebalancing opportunities in many years.

Now place this portfolio in different regimes. In a disinflationary environment with stable growth, sovereign bonds may hedge equity risk as yields trend lower. The joint behavior suggests high diversification power. In a regime shift to persistent inflation, the bond hedge weakens or reverses as real yields rise. Commodities and inflation-linked bonds gain relevance, but their volatility and cyclical behavior can be pronounced. If a growth downturn arrives alongside inflation pressure, correlations across equities, real estate, and credit can converge, reducing diversification. The cash buffer helps operationally but dilutes return while the regime persists. The realized outcome reflects the interaction of macro drivers more than the mere count of line items.

From a factor lens, the same portfolio may have three dominant exposures: equity growth risk, interest rate duration, and inflation. If these three explain most of the variance across time, no amount of fine slicing within each bucket removes the shared drivers. The limit is not the number of holdings but the span of independent risks that are both accessible and reliable at scale.

Scenario and Stress Testing to Understand Limits

Because statistical measures can be backward looking, scenario analysis is a useful complement for understanding diversification ceilings. Historical episodes such as 1970s inflation, 2008 financial crisis dynamics, or 2022 rate shocks provide concrete tests for how a portfolio might behave when relationships change. Hypothetical scenarios can stretch beyond the recorded past to consider new policy regimes or liquidity events. The goal is not prediction but awareness of where diversification could fail and what the distribution of outcomes might look like if correlations spike.

Governance, Policy Ranges, and Monitoring

Diversification operates within a governance framework. Policy ranges define how much drift is acceptable before rebalancing. Monitoring focuses on whether risk contributions or factor exposures are deviating from intent. Limits of diversification suggest that policy should acknowledge the possibility of correlation instability, liquidity constraints, and estimation error. Clarity about how the portfolio will behave under stress reduces the chance of forced, reactive changes that crystallize losses.

Implications for Measurement

Several measurement approaches illuminate the limits in practice:

- Marginal contribution to risk. Quantifies how each position changes total portfolio volatility. A small marginal contribution from added holdings can indicate diminishing diversification value.

- Drawdown overlap. Measures how often holdings experience drawdowns at the same time. High overlap signals limited diversification at the times it matters most.

- Principal component analysis. Reveals how many factors explain most variance. A high share in the first component points to a tight diversification ceiling.

- Liquidity heat maps. Track market depth and transaction costs across assets. When heat maps align during stress, the practical limit tightens.

These tools do not eliminate limits, but they clarify where they likely reside.

Putting Limits in Perspective

Recognizing limits is not a critique of diversification. It is a reminder to treat diversification as a powerful but bounded tool that interacts with regimes, liquidity, and behavior. Portfolios can still benefit substantially from combining independent risks, especially across long horizons in which different environments tend to arrive in sequence. The central point is that diversification reduces risk most effectively when exposures are genuinely independent, when relationships remain reasonably stable, and when implementation can be carried out without undue cost or delay. Where these conditions weaken, the expected benefit approaches its natural ceiling.

Key Takeaways

- Diversification reduces idiosyncratic risk but cannot eliminate systematic risk driven by common macro and liquidity factors.

- Correlations change across regimes and often rise in market stress, which caps the practical benefit of diversification.

- Hidden factor exposures, such as equity beta, duration, and liquidity, can dominate portfolio variance despite many line items.

- Implementation frictions, estimation error, and governance constraints erode theoretical diversification gains.

- For long-horizon planning, framing diversification through independent risk drivers and stress scenarios helps set realistic expectations about its limits.