Common stock and preferred stock are the two principal forms of equity that corporations issue to raise capital. Both represent ownership interests, yet they convey different rights, priorities, and economic exposures. Understanding these differences helps clarify how corporations finance themselves, how control is exercised, and how cash flows are distributed across the capital structure.

Position in the Corporate Capital Structure

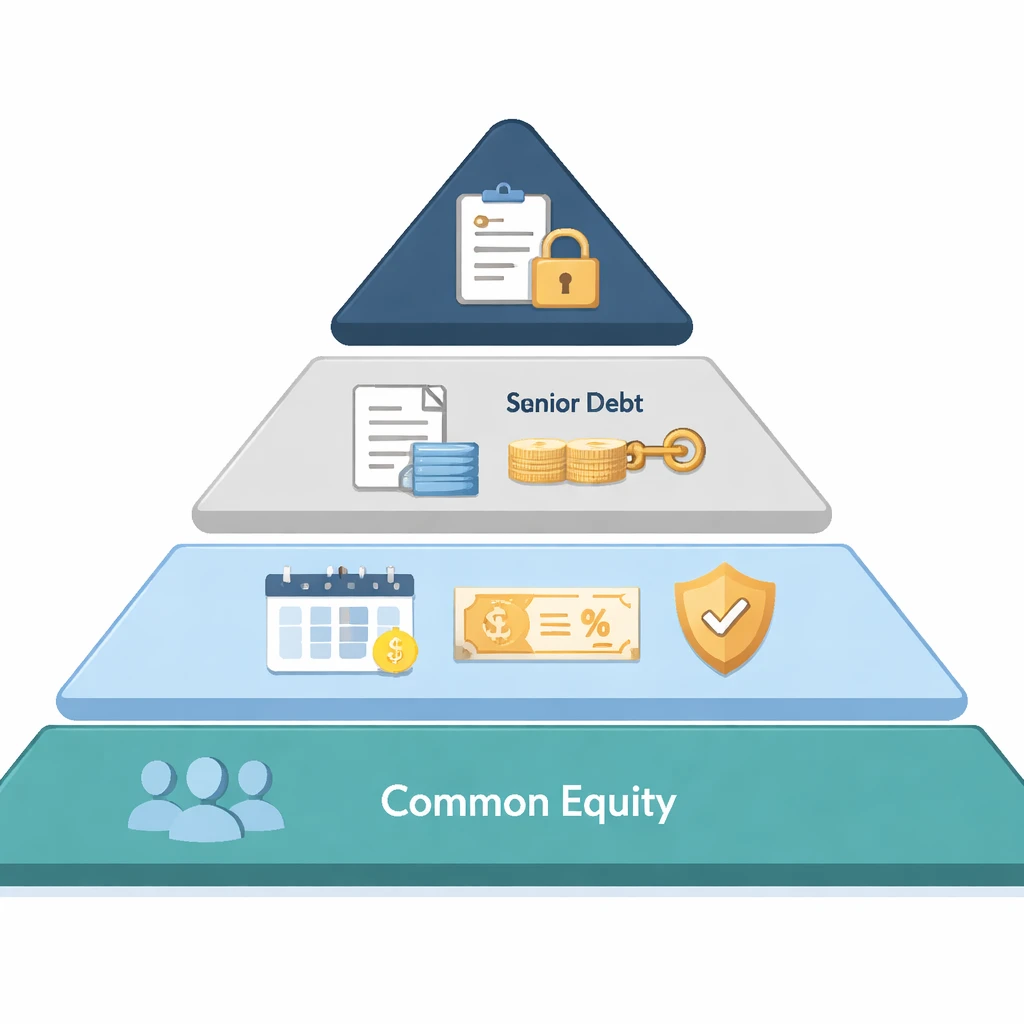

A corporation’s capital structure is typically organized by seniority of claims on assets and cash flows. At the top sit secured debt and other obligations with specific collateral. Unsecured debt follows, then hybrid instruments that blend debt and equity features. Equity is the residual layer that absorbs variability after all contractual claims are satisfied.

Common and preferred stock both reside within the equity category, yet preferred stock typically sits above common in priority. If the corporation distributes dividends or faces liquidation, preferred holders generally rank ahead of common holders but behind all creditors. This priority framework ties directly to the distinct rights attached to each class.

Core Definitions

Common Stock

Common stock represents the fundamental ownership claim on a corporation. Holders usually have voting rights, including the right to elect directors and approve major corporate actions. Common stockholders are the residual claimants, meaning they receive assets and dividends after all fixed obligations and preferential claims are met. The potential upside is tied to the firm’s long-term growth, profitability, and reinvestment decisions. The key trade-off is that common stock is junior in priority and more sensitive to changes in expected earnings and market sentiment.

Preferred Stock

Preferred stock is an equity class with contractual features that prioritize dividends and, in many cases, offer other protections. Preferred shares typically carry a fixed or formula-based dividend rate and a higher claim on distributions than common shares. Many preferred issues are nonvoting or have limited voting rights, especially when the issuer is current on dividends. Because preferred stock combines contractual payment features with equity status, it is often described as hybrid capital.

Why These Categories Exist

Corporations issue common and preferred stock to balance control, flexibility, and financing needs. Several considerations motivate the use of preferred stock alongside common:

- Financing flexibility: Preferred dividends can be structured as fixed, floating, or variable by formula. This gives the issuer flexibility in setting predictable cash obligations without creating traditional debt.

- Dividend discretion: Many preferred dividends are discretionary to a degree, especially relative to debt interest, which reduces default risk tied to temporary earnings shortfalls.

- Regulatory and rating agency treatment: Certain preferred securities receive partial equity credit from rating agencies or favorable treatment in regulatory capital frameworks, particularly for financial institutions.

- Control considerations: Issuers can raise capital without granting proportional voting power, since most preferred issues have limited or contingent voting rights.

- Investor segmentation: Preferred stock can appeal to investor segments seeking more stable income characteristics than common stock typically delivers, without taking on full bond-like constraints.

Common stock remains the foundation of corporate ownership and control. It provides the broadest participation in firm outcomes, including voting on directors and potential gains from retained earnings and capital appreciation.

Voting Rights and Control

Common shareholders typically vote on directors, mergers, major asset sales, and equity compensation plans. Many companies have one class of common stock with one vote per share, although multiple classes are common in certain sectors. If multiple classes exist, one class may have enhanced voting rights combined with constraints on transferability. These arrangements are governed by the corporate charter and state law.

Preferred shareholders often have limited or no voting rights while the issuer is current on dividends. Voting rights for preferred shares may spring into effect if the issuer omits dividends for a defined period. In some structures, preferred holders gain the right to elect a limited number of directors during such periods. These provisions are designed to protect preferred investors when payment discipline weakens.

Dividend Mechanics and Priority

Dividends on common stock are declared at the discretion of the board. The board assesses profitability, cash needs, investment opportunities, and debt covenants before declaring and paying dividends. There is no contractual obligation to pay a common dividend in a given period.

Preferred dividends are specified in the security’s terms, often as a percentage of par value. For example, a $25 par perpetual preferred with a 6 percent stated rate implies an annual dividend of $1.50 per share, typically paid in quarterly installments of $0.375. While the board must still declare preferred dividends, the terms make the amount and schedule more formulaic. Priority rules usually require that preferred dividends be paid before any common dividends are distributed.

Cumulative vs Noncumulative

A key feature is whether unpaid preferred dividends accumulate. Cumulative preferred requires that any skipped dividends accrue in arrears and be paid before common dividends resume. Noncumulative preferred does not accumulate unpaid amounts. Many bank preferred issues are noncumulative to align with regulatory capital requirements. Utility and industrial issuers have historically used cumulative preferred more frequently.

Participating Preferred

Participating preferred allows holders to receive their fixed dividend plus an additional amount if certain conditions are met, such as dividend thresholds for common shares. This feature increases alignment with common stock performance without relinquishing priority on the base dividend.

Fixed-to-Floating and Rate Resets

Some preferred shares pay a fixed rate for a period and then convert to a floating rate tied to a reference index, or reset at a spread over a market rate. These designs moderate interest rate risk over time and can align payments with changes in market conditions.

Liquidation Preferences

In liquidation, claims are paid in order of seniority. Creditors, including bondholders and lenders, must be paid first. Preferred shareholders then receive their liquidation preference, often tied to par value plus unpaid cumulative dividends if applicable. Common shareholders receive any residual value that remains.

This priority structure shapes the risk profile for each class. Preferred holders benefit from a higher likelihood of recovering a portion of their capital in distress, while common holders are last in line but retain maximum upside if the firm remains a going concern and grows.

Variations Within Common and Preferred

Classes of Common Stock

Companies may issue multiple classes of common stock that differ in voting rights, conversion features, or other terms. For example, Class A may hold one vote per share, while Class B carries multiple votes per share. Economic rights on dividends and liquidation are often the same, but not always. The specifics are defined by the corporate charter, and public filings describe any differences that affect shareholder rights.

Types of Preferred Stock

- Perpetual preferred: No maturity date, often callable by the issuer after a specified period.

- Term preferred: Has a stated maturity and redemption amount.

- Callable preferred: Redeemable by the issuer at par or a defined price after a call date, subject to notice provisions.

- Convertible preferred: Can convert into common shares according to a fixed or adjustable conversion ratio. Conversion can be optional, mandatory, or contingent on specified events.

- Trust preferred and deeply subordinated hybrids: Structures that use a trust or special purpose vehicle. These have been more common among financial institutions in certain historical periods.

How the Securities Trade and Settle

Common and preferred shares are issued in the primary market and then trade in the secondary market on exchanges or over-the-counter venues. Listing conventions differ by venue. Preferred tickers often use suffixes or series identifiers to distinguish among multiple preferred issues from the same issuer. Prices quote per share, with many preferred issues designed around a $25 par format, although $50, $100, or $1,000 par values also exist.

Dividend timelines follow record and payment date mechanics. The ex-dividend date indicates when new buyers no longer receive the upcoming dividend. For preferred issues with quarterly schedules, the ex-dividend timetable becomes a notable part of the trading calendar. Settlement cycles typically mirror those for common shares, subject to the rules of the trading venue.

Illustrative Examples

Utility Company with Cumulative Preferred

Consider a regulated utility that maintains stable cash flows. It issues a $25 par cumulative perpetual preferred at a 5.5 percent rate, implying $1.375 in annual dividends. If an economic shock leads the board to suspend preferred dividends for two quarters, unpaid amounts accumulate. Before any common dividend is reinstated, the company must catch up on all preferred dividends in arrears. This structure supports predictable income for preferred holders while preserving some discretion during stress.

Bank Issuing Noncumulative Preferred

A large bank issues noncumulative perpetual preferred shares that qualify for additional regulatory capital treatment. The stated rate is fixed for five years at 6.25 percent, then floats at a spread over a reference rate. If the bank omits a dividend during a period of earnings pressure, that payment does not accrue. When conditions improve, the bank can resume preferred dividends prospectively without owing past amounts. The security’s terms aim to provide regulatory resilience and reduce pressure on cash flows during stress.

Tech Company with Only Common Stock

A growing technology company may rely solely on common stock and convertible debt rather than preferred equity. With variable earnings and significant reinvestment needs, the board might choose not to declare common dividends for many years. Shareholder value is expected to be realized through reinvestment, innovation, and potential capital gains rather than cash distributions. This example underscores the flexibility of common equity as a long-horizon claim on the firm’s residual value.

Governance, Charters, and Prospectuses

Rights for each class of stock are created and limited by corporate charters, bylaws, and the terms of specific security offerings. For preferred stock, the prospectus or offering memorandum sets out coupon type, rate, payment schedule, seniority, call terms, conversion features, cumulative status, voting triggers, and liquidation preference. The common stock section of the charter defines voting rights, potential preemptive rights if any, and procedures for corporate actions such as mergers or share issuance.

Corporate governance also defines how boards interact with shareholders. Common shareholders elect directors who oversee strategy and appoint management. Preferred shareholders may gain voice under defined conditions, such as the election of special directors if dividends are in arrears for several consecutive periods. These mechanics create checks and balances between cash flow priority and control.

Accounting and Regulatory Context

Financial reporting recognizes the differences between common and preferred shares in several ways. Under U.S. GAAP, dividends on preferred stock that is classified as equity are typically treated as distributions to preferred shareholders and deducted from net income available to common when calculating earnings per share. If a preferred instrument is mandatorily redeemable or embodies an unconditional obligation to transfer assets, it may be classified as a liability, with payments recorded as interest expense. IFRS follows similar principles, focusing on whether an instrument creates a contractual obligation to deliver cash or another financial asset.

Regulatory frameworks matter for certain issuers. Banks and insurers may issue preferred shares that receive partial equity credit in capital adequacy calculations. The specific criteria include features such as permanence, subordination, and discretion to cancel dividends. These rules influence the prevalence of noncumulative perpetual preferred among financial institutions.

Valuation Perspectives

Common stock valuation often focuses on expectations for earnings, cash flow growth, and reinvestment returns. Price sensitivity reflects changes in growth prospects and required returns. Because common shareholders are residual claimants, small changes in expected performance can lead to large swings in value.

Preferred stock valuation anchors on stated dividends, credit quality, call features, and interest rate conditions. A $25 par preferred with a 6 percent fixed rate tends to trade around par if market yields match the coupon, trade above par if market rates fall, and below par if market rates rise, all else equal. Callable structures add an additional dimension. If the issue becomes likely to be called at par after a no-call period, price appreciation above par may be limited by the call price.

Convertible preferred adds a link to common stock performance. The security behaves like preferred until the common stock price rises toward the conversion threshold. At higher levels, the value increasingly reflects the embedded option to convert into common shares.

Risk Profiles

- For common stock: Highest volatility among equity layers, residual claim in liquidation, exposure to dilution from new share issuance or option exercises, and dependence on management’s capital allocation and profitability.

- For preferred stock: Priority in dividends and liquidation relative to common, but still subordinated to all debt. Sensitivity to interest rates for fixed-rate issues, call and reinvestment risk if redeemed, and the possibility of dividend suspension. Noncumulative structures eliminate arrears, which changes the trade-off between flexibility for the issuer and dividend continuity for holders.

How the Concepts Operate in Practice

Both common and preferred holders rely on clearly defined corporate actions. Dividends must be declared by the board, with record and payment dates communicated publicly. Ex-dividend dates determine entitlement for buyers and sellers around the record date. Conversion or call notices for preferred issues follow defined procedures and timelines. In mergers and acquisitions, preferred holders may see their shares assumed by the acquirer, redeemed according to terms, or converted into the acquirer’s securities depending on the governing documents.

Index inclusion also differs. Broad equity indices usually focus on common shares, particularly the primary class with full liquidity. Preferred issues are sometimes tracked by specialized indices. This separation contributes to differences in investor base, liquidity patterns, and pricing dynamics.

Distinguishing Public Preferred from Private Venture Preferred

Private companies frequently issue preferred stock to venture investors with terms designed for early-stage financing. These securities can include investor protections such as full ratchet or weighted-average anti-dilution, redemption rights, and board seats. The focus is on control, downside protection, and staged financing. Publicly traded preferred stock typically has simpler economic terms, focuses on dividend priority, and relies on market liquidity rather than negotiated control rights. Both occupy the preferred category but serve different corporate and investor needs.

Reading the Term Sheet: What Matters Most

For preferred stock, several items in the prospectus meaningfully shape outcomes:

- Dividend structure: Fixed, floating, or fixed-to-floating, frequency, and whether dividends are cumulative.

- Seniority: Precise ranking relative to other preferred series and to junior or senior securities.

- Call and redemption terms: First call date, call price, and any special redemption rights.

- Conversion rights: Ratio, triggers, optional or mandatory conversion mechanics, and adjustments for corporate actions.

- Voting: Conditions under which voting rights arise, especially related to dividend omissions.

- Liquidation preference: Par amount and treatment of unpaid cumulative dividends, if applicable.

For common stock, key documents include the corporate charter and bylaws, which delineate classes, voting rights, and any limitations on transfer or ownership. Public filings also explain stock-based compensation plans, potential dilution sources, and policies around dividends and buybacks.

Real-World Context and Market Conventions

Market practice has developed conventions that shape how these securities are issued and traded. Many preferred issues are structured around round-number par values, which simplifies quotation and call mechanics. Exchange tickers for preferred shares often include a series letter, such as Series A or Series B, reflecting multiple issuances from the same company. Disclosure practices are standardized through securities regulations that specify how terms must be presented, which supports comparability across issuers.

Liquidity can differ meaningfully. Primary classes of common stock usually trade with high volume, while preferred issues can be less liquid, especially for smaller series. The investor base for preferred shares includes institutions that focus on income-oriented or regulatory objectives. These differences influence bid-ask spreads, depth, and how prices respond to market-wide rate changes or issuer-specific news.

Putting It All Together

Common stock and preferred stock are built to divide control rights and cash flow priorities in ways that align with a corporation’s financing strategy. Common stock concentrates voting power and residual upside. Preferred stock introduces contractual features that shape cash distribution and seniority without turning the instrument into debt. Each serves a distinct purpose in the corporate toolkit and interacts with legal, accounting, and regulatory frameworks.

A clear mental model is useful. Start with the capital structure ladder: debt at the top in priority, then preferred, then common as the residual. Add the dividend rules: preferred dividends follow stated terms and precede any common dividends, subject to declaration. Overlay the governance layer: common typically votes continuously, preferred votes when triggered by specified events. Finally, consider callability, convertibility, and cumulative status, which combine to determine how each instrument behaves through the business cycle.

Key Takeaways

- Common stock carries voting rights and residual claims, while preferred stock prioritizes dividends and liquidation rights but often limits voting.

- Preferred stock sits above common in the equity layer of the capital structure and can include cumulative, callable, or convertible features.

- Dividend mechanics differ: common dividends are discretionary, and preferred dividends follow stated terms, with priority over common distributions.

- Legal charters and prospectuses define rights, including voting triggers, call provisions, and liquidation preferences that determine outcomes in stress or corporate actions.

- Issuers choose between common and preferred to balance control, financing flexibility, and regulatory considerations, resulting in distinct investor bases and risk profiles.