Indexing allows investors to hold a diversified basket of securities designed to mirror a market benchmark. Two of the most common vehicles that implement indexing are index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. They serve the same core purpose, but they differ in how shares are created, how prices are formed, when trades occur, and how costs and taxes are experienced by the holder. Understanding these differences is part of basic market literacy because index funds and ETFs now sit at the center of equity and bond markets globally.

Definitions and Core Mechanics

What is an index mutual fund

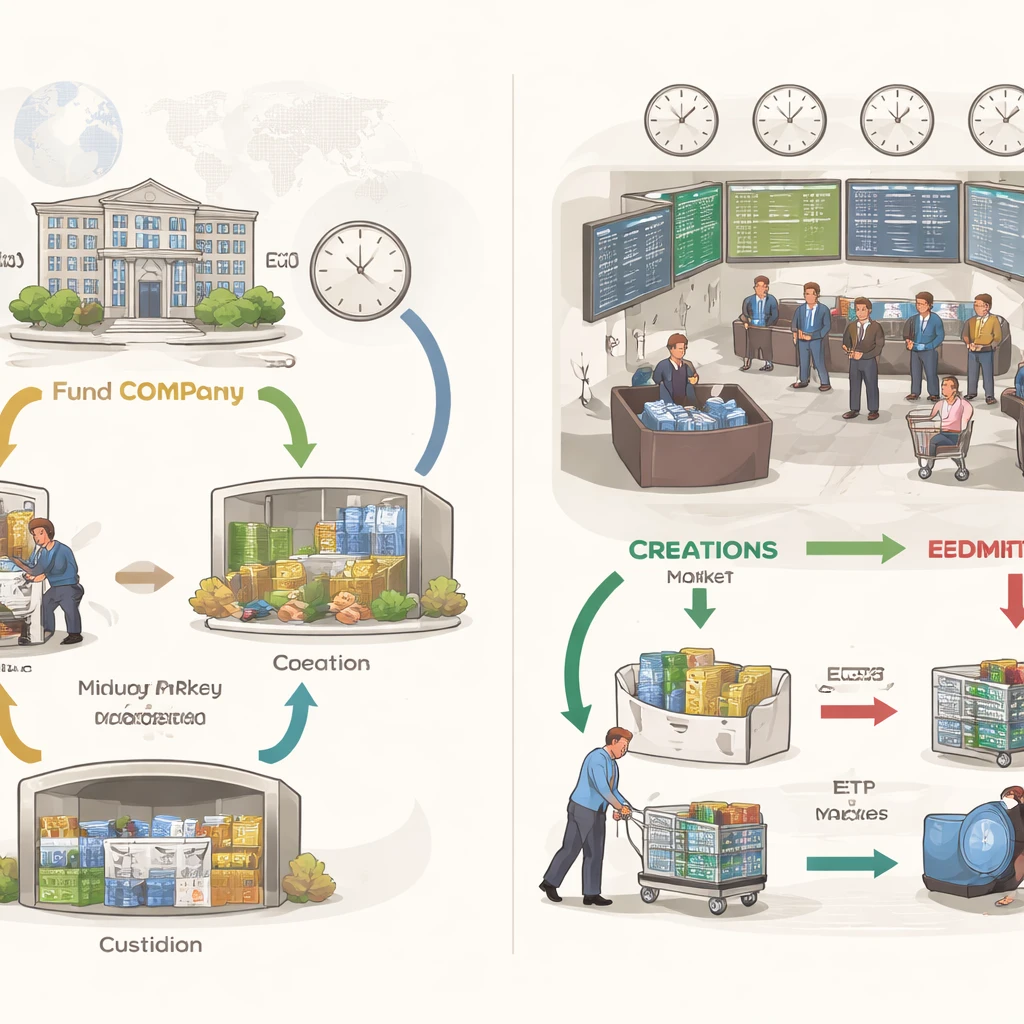

An index mutual fund is a pooled investment vehicle that seeks to match the performance of a stated index. It is typically organized as an open-end fund. Shares are bought from and redeemed with the fund company at the fund’s net asset value, or NAV, which is calculated once per day after the markets close. Orders placed during the trading day execute at the end-of-day NAV.

Because trading occurs directly with the fund, there is no secondary market for mutual fund shares. The fund’s portfolio managers adjust holdings to track the index, using either full replication or sampling. Fund expenses are deducted from assets and reported as an annual expense ratio. Some funds also earn securities lending revenue that may offset a portion of expenses, depending on the manager’s program and policies.

What is an ETF

An exchange-traded fund is also a pooled vehicle that generally seeks to track an index, but it is listed on an exchange and trades throughout the day at market prices. Investors buy and sell ETF shares in the secondary market through brokerages, just like common stock. In the background, a separate creation and redemption process connects the ETF’s market price with its underlying holdings.

Authorized participants, typically large broker-dealers, can assemble or deliver a basket of the underlying securities that mirrors the fund’s portfolio. In return they receive or redeem large blocks of ETF shares called creation units. This in-kind exchange helps keep the ETF’s market price close to its intraday indicative value by allowing arbitrage when premiums or discounts appear.

ETFs also publish a daily holdings file and an intraday estimate of value. Although the intraday estimate is not a tradable price, it provides a reference for market makers who quote bids and offers on the exchange.

How These Vehicles Fit Into Market Structure

Primary and secondary markets

Index mutual funds operate only in the primary market. All transactions are between investors and the fund company at NAV. Cash flows into or out of the fund result in the fund buying or selling underlying securities. Liquidity for fund shareholders comes from the fund’s ability to process subscriptions and redemptions at the close.

ETFs interact with both markets. Most investors trade in the secondary market on an exchange. Liquidity is provided by market makers who quote prices, and by natural buyers and sellers. When supply and demand in the secondary market become unbalanced, authorized participants use the primary market to create or redeem shares with the issuer. The ability to swap baskets for ETF shares anchors prices to underlying value and is a central feature of the ETF structure.

Roles of issuers, custodians, and index providers

Both structures rely on a chain of institutions. The fund sponsor designs the product and oversees operations. A custodian bank safekeeps the portfolio’s assets. An index provider defines the methodology, rebalances the index on a schedule, and licenses its intellectual property to the fund. For ETFs there are additional players: market makers maintain quotes and inventory, and authorized participants interface with the issuer for creations and redemptions. Regulators oversee disclosure, sales practices, and fund governance.

Why Index Funds and ETFs Exist

The appeal of indexing grew from decades of research showing that broad market returns are hard to beat after fees. Index vehicles offer diversified exposure with transparent rules and relatively low operating costs compared with many actively managed alternatives. As indexes expanded from large-cap equities to small caps, international markets, bonds, and thematic exposures, funds that follow those benchmarks provided a simple way to hold entire market segments in a single security.

The structures differ because investors have different needs. Some prefer the end-of-day simplicity of mutual funds. Others value the intraday tradability of ETFs for operational reasons such as cash management, transitions between managers, or precise control over the timing of gains and losses within a trading day. Institutions also use ETFs to equitize cash or to establish temporary market exposure while moving underlying portfolios.

Where They Are Similar

Index mutual funds and ETFs share several characteristics:

- Both aim to track a stated index as closely as practical, subject to operating constraints and costs.

- Both often achieve broad diversification within the scope of their index.

- Both charge expense ratios that are typically lower than many active vehicles covering the same markets.

- Both disclose holdings and follow index rebalancing calendars that are known in advance.

- Both may use full replication or sampling techniques to track the index, and both can experience tracking error.

Key Differences

How and when shares trade

Mutual fund shares transact at NAV once per day. Investors submit orders through the fund company or an intermediary and receive the closing price. ETFs trade continuously on exchanges. Investors can place market or limit orders, and the execution price depends on prevailing bids and offers at the time of the trade. The ETF’s last price can be above or below its NAV during the day, although arbitrage and competition among market makers typically limit persistent gaps.

Price formation and transaction costs

For mutual funds, the only price is the closing NAV, and there is no bid-ask spread. Some mutual funds have purchase or redemption fees, and some platforms assess transaction fees, but there is no separate trading spread. For ETFs, the investor faces an explicit bid-ask spread and potential brokerage commissions, plus any market impact from large orders. The spread compensates liquidity providers for inventory risk and operating costs. High-quality underlying liquidity and active market making tend to support tighter spreads.

Premiums and discounts

Mutual fund investors do not experience premiums or discounts relative to NAV because transactions occur directly with the fund at NAV. ETF investors can see market prices trade at small premiums or discounts to NAV during the day. The creation and redemption mechanism helps align the two, but during periods of market stress or when the underlying market is closed, deviations can widen.

Tax treatment

Tax outcomes depend on jurisdiction and individual circumstances. In the United States, ETFs often reduce capital gains distributions through in-kind redemptions that allow the fund to remove low-cost-basis lots without selling them for cash. Index mutual funds may distribute more capital gains because subscriptions and redemptions are usually handled in cash. There are exceptions. Some fund families operate both a mutual fund and an ETF as share classes of the same portfolio, which can mitigate capital gains distributions for the mutual fund. Outside the United States, tax rules differ and the ETF in-kind mechanism may not have the same effects.

Automation and minimums

Mutual funds commonly support automatic investments and withdrawals in fixed dollar amounts, and many retirement plans are designed around this functionality. ETFs trade in share quantities, though some brokerages offer fractional share trading and automatic investments. Minimum initial investments are common in mutual funds, while ETFs typically require only the price of one share plus associated trading costs.

Operational roles

ETFs rely on market makers and authorized participants to maintain liquid secondary trading and to keep prices aligned with NAV. Mutual funds rely on transfer agents and the fund’s own liquidity management to meet orders. These differences affect how each vehicle behaves during volatile periods and how investors experience execution.

Costs in Practice

Expense ratios

Both vehicles charge annual operating expenses. These cover index licensing, custody, administration, and management. Expense ratios are deducted from fund assets over time and are observable in a fund’s prospectus or fact sheet. Competition has driven many broad market index funds and ETFs to very low headline fees, but the expense ratio is only one component of total cost.

Trading costs

Mutual fund investors pay or receive NAV with no spread, but may face platform fees or purchase and redemption fees where applicable. ETF investors pay the spread and any brokerage commissions. For small orders in liquid ETFs, spreads can be a few basis points. For less liquid exposures such as certain small-cap or niche markets, spreads are often wider. Large ETF orders can be executed through block trading desks that coordinate with market makers, which can reduce visible impact but still involve implicit costs.

Tracking difference and tracking error

Tracking difference is the realized return gap between the fund and its index over time, usually negative by the amount of expenses plus any friction. Tracking error is the variability of that gap from period to period. Causes include fees, sampling methods, cash drag from dividend timing, and the costs of rebalancing when the index changes constituents. Both index mutual funds and ETFs can achieve very low tracking error in highly liquid markets such as large-cap equities and developed market government bonds. Tracking becomes more challenging when the index includes illiquid securities, limited access markets, or complex derivatives.

Securities lending and revenue sharing

Many index funds and ETFs lend securities to borrowers such as market makers and hedge funds. Collateral is posted and lending revenue is shared between the fund and the lending agent. This revenue can offset expenses and improve tracking. Programs vary in scale, risk controls, and how much revenue is returned to the fund.

Premiums, Discounts, and the ETF Arbitrage Mechanism

The ETF price reflects supply and demand among exchange participants. If the ETF trades above the value of its underlying basket, an authorized participant can buy the underlying securities and deliver them to the issuer in exchange for new ETF shares. Those shares are then sold in the market, which tends to push the ETF price down toward NAV. If the ETF trades below basket value, the process is reversed. This mechanism is effective when underlying markets are open and liquid.

Premiums and discounts can appear for reasons unrelated to malfunction. When the underlying market is closed, the ETF may serve as a price discovery vehicle. International equity ETFs that trade in New York while their local exchanges are closed often show apparent premiums or discounts when compared to stale NAVs based on the prior local close. During stressed markets, spreads widen and the cost to conduct arbitrage increases, which can permit larger deviations until conditions normalize.

Tracking and Replication Methods

Index vehicles use several techniques to match the benchmark:

- Full replication. The fund holds every security in the index at its index weight. This is feasible when the index contains liquid constituents and manageable total names.

- Sampling or optimization. The fund holds a subset of securities selected to approximate the index’s risk and return characteristics. This is common when the index has thousands of names, includes illiquid securities, or spans many small positions where trading costs would outweigh precision.

- Synthetic replication. Some funds, more common outside the United States, use derivatives such as swaps to obtain index exposure. The fund holds a collateral basket and enters into a swap that delivers the index return. This can improve tracking in difficult markets but introduces counterparty considerations and depends on local regulation.

Rebalancing occurs on a schedule set by the index provider. Funds must trade to accommodate additions, deletions, and weight changes. The predictability of rebalances means that liquidity can cluster around these dates, but it also means that front-running and market impact are practical concerns. Efficient trading strategies and the ability to cross trades internally across a large family of funds can reduce costs, though some slippage is unavoidable.

Distributions, Dividends, and Taxes

Index funds and ETFs both collect dividends and interest from their holdings. They distribute this income on a set schedule, commonly quarterly for equities and monthly for many bond funds. Some funds accumulate dividends and pay them as part of a periodic distribution. Dividend reinvestment is straightforward for mutual funds because new shares are issued at NAV without a spread. For ETFs, dividend reinvestment plans offered by brokerages typically reinvest on the pay date or shortly afterward by purchasing additional shares in the market. Fractional reinvestment is platform dependent.

Capital gains distributions occur when the fund realizes gains that cannot be offset by losses. As noted, the in-kind creation and redemption process can help ETFs manage gains in the United States by allowing the removal of low-basis positions. Tax outcomes vary by investor and by country. Rules for withholding, qualified dividends, and fund domicile can all affect after-tax experience. Investors often consult tax resources or advisors to understand the implications for their situation and jurisdiction.

Real-World Context and Examples

Broad equity market exposure

Consider a large-cap U.S. equity index tracked by both an ETF and a mutual fund. The ETF trades all day with a typical spread of a few cents and publishes the basket daily. The mutual fund accepts orders until market close and executes at NAV. Over a year, the headline expense ratios are similar. The experienced total cost can differ for short holding periods, where ETF trading costs are more material, versus long holding periods, where the expense ratio and tracking difference dominate. Neither structure guarantees better outcomes; the realized experience depends on how it is used within an investor’s constraints.

International markets and market hours

An ETF that holds Japanese equities and trades during U.S. hours often appears to deviate from its last published NAV when the Tokyo market is closed. The ETF’s price reflects new information and currency moves during U.S. hours. The following day, when Tokyo opens, the NAV typically updates and the apparent gap narrows. A mutual fund tracking the same index will process orders at its NAV calculated after the local market close, which already incorporates those moves.

Bonds and liquidity

Bond markets are less transparent than equities. ETFs can help aggregate fragmented liquidity by serving as a single entry point. During periods of credit stress, ETF prices sometimes move more quickly than the reported prices of individual bonds. This does not necessarily mean the ETF is broken; it can mean the ETF is reflecting changes in required yields before many bonds trade. In calm markets, index mutual funds and bond ETFs tracking the same benchmark often show similar long-run performance with small differences arising from expenses and implementation details.

Cash management and implementation

Institutional investors sometimes use ETFs to equitize cash while awaiting funding or manager transitions. The ability to enter and exit intraday and to trade in blocks with market makers is operationally useful. By contrast, automatic payroll deductions into retirement plans are often routed to mutual funds because plan recordkeeping systems are built around end-of-day NAV processing and fixed dollar contributions.

Operational and Counterparty Considerations

Both structures rely on service providers and present operational risks. Custodians hold assets and must be selected for financial strength and operational controls. Index licensing creates dependencies on the methodology and governance of the index provider. For ETFs, concentration among a small number of authorized participants can matter during stress if one AP experiences technical issues or risk constraints. Market makers manage inventory and hedge, which can affect spreads when volatility spikes. Mutual funds must meet redemptions and may hold cash buffers or use lines of credit to manage flows. Liquidity management rules and disclosures outline these practices.

A Framework for Comparing Index Funds and ETFs

Choosing a vehicle involves matching product mechanics to practical constraints rather than seeking a universally superior structure. A structured comparison can help clarify trade-offs without implying a recommendation:

- Time horizon and trading frequency. Long horizons make ongoing expenses and tracking difference more important. Short horizons make one-time trading costs more visible.

- Order control. If intraday execution, limit orders, or specific timing are needed, ETFs provide those tools. If end-of-day pricing is sufficient or preferred, mutual funds are straightforward.

- Tax jurisdiction. Local tax rules can change the relative attractiveness of in-kind redemptions and the treatment of distributions. Fund domicile also matters for withholding on dividends.

- Platform and plan design. Retirement plans often integrate with mutual funds. Brokerage platforms offering fractional shares and dividend reinvestment can make ETFs behave similarly to funds for small periodic contributions.

- All-in cost. Consider expense ratios, bid-ask spreads, potential commissions, and expected tracking difference. For large ETF orders, execution approach influences cost.

- Liquidity of the underlying index. Funds tracking highly liquid markets generally offer tighter spreads and lower tracking error. Niche or less liquid exposures may have wider spreads or larger deviations.

Common Misconceptions

- ETFs are always more liquid than the underlying securities. ETF liquidity ultimately depends on the liquidity of the underlying basket and the ability of market makers to hedge. High trading volume in the ETF does not eliminate underlying market constraints.

- ETF price equals NAV. The ETF trades at market prices that can deviate from NAV. The creation and redemption process encourages alignment, but small gaps are normal, and larger ones occur at times.

- Expense ratio tells the whole cost story. Spreads, taxes, and tracking difference contribute to realized outcomes. A slightly higher fee can be offset by better tracking or lower trading costs.

- Mutual funds never distribute capital gains and ETFs always avoid them. Both statements are false. Mutual funds can be tax efficient in some structures and years. ETFs can distribute gains, especially in specialized strategies or during index changes with limited liquidity.

- Index funds and ETFs are risk free. They carry market risk that matches their index, plus operational and tracking risks. Even broad diversification does not eliminate drawdowns.

Putting It All in Broader Market Context

Index funds and ETFs have reshaped how capital is allocated. Their scale influences trading volumes, corporate governance, and even the structure of new indexes. Market making in ETF shares is now an important component of daily exchange activity. At the same time, the basic economic function is unchanged: both vehicles hold underlying securities and pass through those risks and returns to holders with relatively little friction. Neither structure guarantees a better return than the benchmark it tracks, and neither structure removes the fundamental risks inherent in the markets they follow.

Understanding how each vehicle operates helps interpret price behavior during volatile periods and routine rebalances. It also clarifies why the same index can be accessed through different wrappers that appear similar on the surface but behave differently at the point of transaction, taxation, and operations.

Key Takeaways

- Index mutual funds and ETFs both aim to track benchmarks, but they trade and price differently.

- Mutual funds transact at end-of-day NAV, while ETFs trade intraday at market prices with spreads.

- The ETF creation and redemption mechanism aligns prices with NAV and supports secondary market liquidity.

- Total cost depends on expenses, spreads, tracking difference, and taxes, not just headline fees.

- Structural and tax differences vary by market and jurisdiction, so real-world outcomes depend on context.