Exchange-traded funds are often described as tax efficient. The phrase refers to a specific outcome in many jurisdictions where an ETF tends to distribute fewer capital gains to shareholders than a comparable mutual fund. The mechanism is structural, not promotional. It arises from the way ETFs create and redeem shares, and from tax rules that treat in-kind transfers differently from sales for cash. Understanding this mechanism helps place ETFs within the broader market structure that connects investors, market makers, and the underlying securities universe.

Tax efficiency is a property of the fund vehicle and its operating process. It does not eliminate taxes. Investors can still owe taxes on dividends and interest received from an ETF, and on gains when they sell ETF shares. The principal distinction is that many ETFs, particularly those tracking broad equity indexes in the United States, tend to pass through very few capital gains distributions during normal market conditions.

Defining ETF Tax Efficiency

ETF tax efficiency is the tendency of an ETF to minimize taxable capital gains distributions to shareholders relative to other pooled vehicles holding similar assets. The effect is most visible in U.S. equity index ETFs, which often post long stretches without distributing capital gains at year-end. The central channel is the ETF’s primary market, where shares are created and redeemed in kind with large, institutional counterparties called authorized participants.

Tax efficiency should be interpreted precisely. It refers to capital gains distributions at the fund level. It does not refer to income distributions such as ordinary dividends or bond interest. It does not eliminate the investor’s capital gains or losses when the investor sells ETF shares. It is also conditional on legal frameworks. The discussion below uses the U.S. system as the primary reference point, since the most developed set of ETF tax practices aligns with U.S. tax law and securities regulation.

How ETFs Fit into Market Structure

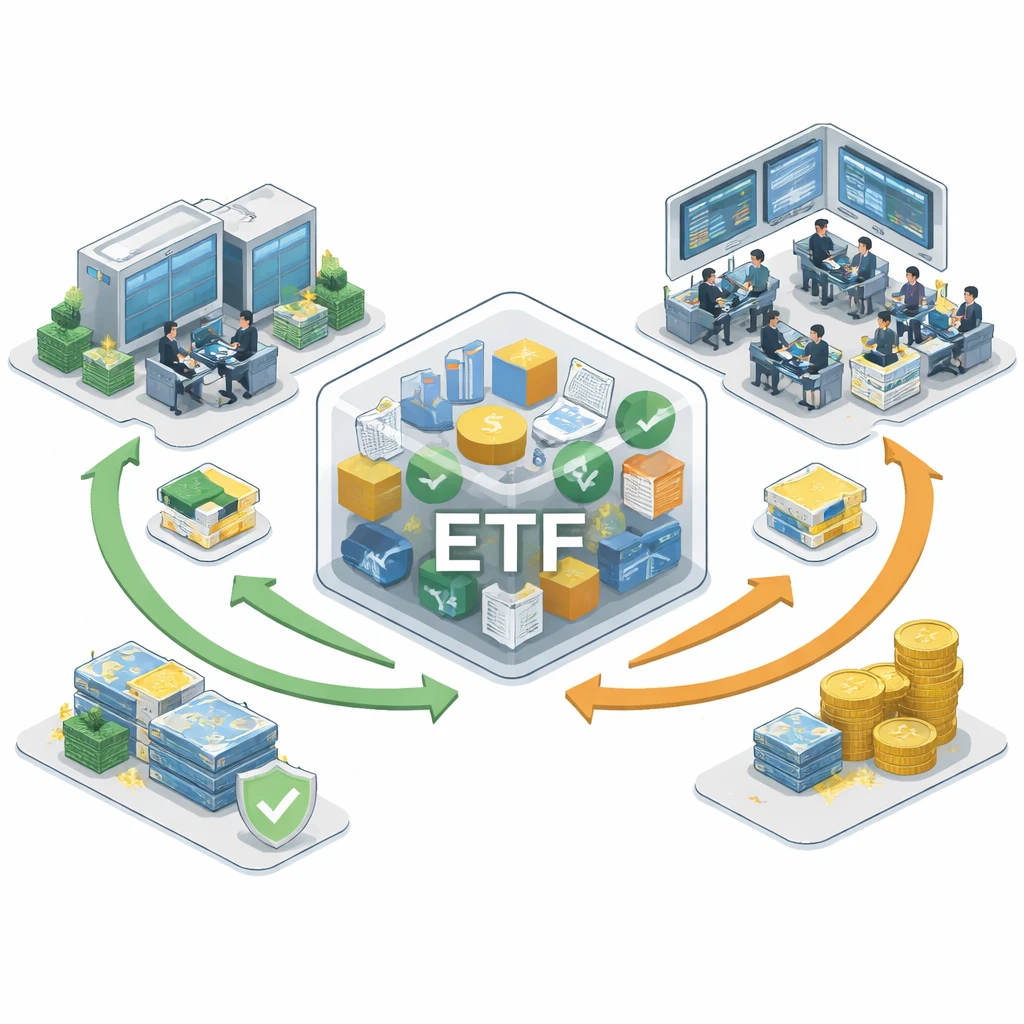

ETFs operate across two tightly linked markets. In the secondary market, investors trade ETF shares on exchanges, and prices stay close to net asset value because market makers can hedge or unwind positions using the underlying securities. In the primary market, authorized participants transact directly with the ETF at net asset value to either create new shares or redeem existing ones. These primary market transactions are typically conducted in kind. The ETF delivers or receives a basket of portfolio securities rather than cash.

This two-tier structure is central to tax efficiency. When an ETF faces redemptions, it normally delivers out a representative basket of securities held in the portfolio rather than selling securities for cash. In the United States, a regulated investment company can distribute appreciated securities in kind to a redeeming party without recognizing a taxable gain at the fund level under Internal Revenue Code Section 852(b)(6). As a result, the ETF can reduce or avoid realizing gains in its portfolio even as it meets redemption demand.

Why the Tax Efficiency Exists

Consider what happens when a traditional open-end mutual fund faces large redemptions. The fund often sells portfolio securities to raise cash, realizes gains on appreciated positions, and must distribute net realized gains to remaining shareholders if gains exceed losses. Investors who did not redeem can receive a capital gains distribution and owe tax even if they did not sell their fund shares.

An ETF facing similar redemption pressure can typically satisfy redemptions in kind. Instead of selling appreciated holdings to raise cash, the ETF transfers those holdings to the authorized participant and retires the corresponding ETF shares. Because an in-kind redemption is not a sale for tax purposes at the fund level, the ETF does not realize those embedded gains. Moreover, ETF portfolio managers often use in-kind redemptions to deliver out the lowest cost-basis lots in the basket. Redemptions therefore remove the most appreciated positions from the portfolio, which reduces the fund’s future embedded gains.

This ability to externalize low-basis lots through in-kind redemptions is pivotal. It means redemption activity can cleanse the portfolio of built-in gains over time, lowering the probability that the fund will later need to make a taxable capital gains distribution. The effect is structural and cumulative, which is why many broad equity ETFs have long records of zero or minimal capital gains distributions.

Mechanics of Creation and Redemption

Primary market participants interact with the ETF in large blocks, often 25,000 to 100,000 shares or more. A creation involves the authorized participant delivering a basket of securities to the ETF in exchange for a block of ETF shares. A redemption involves the reverse. The ETF publishes the daily composition of a standard creation and redemption basket along with cash adjustments to cover minor differences such as corporate actions, accrued income, or transaction costs.

Two operational features matter for taxes:

- In-kind transfers. Transfers of appreciated securities to or from a regulated investment company generally do not trigger capital gains at the fund level under U.S. rules. This preserves unrealized gains within the delivered securities rather than crystallizing them inside the fund.

- Custom baskets. Many ETFs, subject to board oversight and compliance programs, use custom baskets that deviate from the pro rata portfolio. A custom basket can be constructed to include specific low-basis lots for redemptions, or to accommodate liquidity and market impact considerations. The ability to choose which lots are delivered enhances the fund’s control over realized gains.

These features interact with arbitrage. If the ETF trades at a premium to net asset value, authorized participants can create shares in exchange for delivering the underlying securities, then sell ETF shares to capture the premium. If it trades at a discount, they can buy ETF shares, redeem in kind, and sell the underlying. This arbitrage keeps market prices aligned with net asset value while simultaneously enabling the in-kind process that supports tax efficiency.

What Investors Are Taxed On

Tax efficiency concerns fund-level capital gains distributions. At the investor level, taxes can still arise from several channels. The specifics depend on local law and personal circumstances. Under U.S. rules, common categories include:

- Ordinary income distributions. Bond ETFs pass through taxable interest, which is typically taxed as ordinary income. Equity ETFs can distribute nonqualified dividends and other ordinary income.

- Qualified dividend income. Many U.S. and certain foreign equity dividends qualify for reduced tax rates if holding period and other conditions are met at both the fund and investor level.

- Capital gains distributions. While often limited, ETFs can distribute capital gains when realized trades exceed losses and cannot be offset via in-kind mechanisms.

- Investor’s own sale. Selling ETF shares for more than the tax basis results in a capital gain to the investor. Holding period rules determine whether the gain is short or long term.

Tax reporting reflects these categories. U.S. registered investment company ETFs typically report on Form 1099-DIV for distributions and Form 1099-B for investor sales. Some nontraditional structures use different reporting, as discussed below.

Comparing ETFs and Mutual Funds on Taxes

Mutual funds and ETFs both hold diversified portfolios. Both can track indexes or pursue active strategies. The tax divergence often comes from the redemption process, not from the choice of active versus index. Because mutual funds generally meet redemptions in cash, they are more likely to sell appreciated positions and realize gains inside the portfolio, which are then distributed to shareholders. ETFs generally meet redemptions in kind, which allows them to avoid realizing gains and to deliver out low-basis lots.

There are exceptions. A mutual fund can also redeem in kind under certain conditions, although it is uncommon for operational and investor relations reasons. Conversely, an ETF may need to realize gains if it must sell securities for cash to manage corporate actions, index reconstitutions, or liquidity events that cannot be handled in kind. The relative advantage is therefore probabilistic. The ETF structure increases the likelihood of low capital gains distributions, but it is not an absolute guarantee.

Illustrative Example

Suppose an equity ETF tracks a broad index of 1,000 stocks. Over several years, the fund acquires shares in a company at an average cost of 20 dollars that now trade at 50 dollars. The fund holds 1 million shares with a 30 million dollar unrealized gain. If the ETF were a mutual fund facing redemptions equal to one twentieth of assets, it might sell 50,000 shares of the appreciated stock to raise cash, realizing a portion of that 30 million dollar gain. The resulting net realized gains would be distributed to remaining shareholders.

Now consider the ETF using an in-kind redemption. An authorized participant redeems an ETF share block and receives a basket that includes 50,000 shares of the appreciated stock. The ETF cancels the shares and no sale occurs inside the fund. The 50,000 shares carry their low basis out of the fund, reducing the unrealized gains that remain. If the authorized participant then sells those shares in the market, any gain is recognized outside the fund. The remaining ETF shareholders did not receive a capital gains distribution due to this redemption.

Repeat this process across many positions and many redemption events. The ETF can continually remove low-basis lots through in-kind redemptions, leaving the portfolio with higher average cost basis and a smaller embedded gain profile. When index changes force the fund to exit a holding entirely, the remaining embedded gains are lower than they would have been without prior cleansing through redemptions. This is the core of ETF tax efficiency.

When ETF Tax Efficiency Can Be Limited

Several scenarios can reduce or negate the tax advantage:

- High-turnover strategies. Active ETFs or funds tracking indexes with frequent reconstitution may need to trade extensively in the market. If the fund cannot offset sales with in-kind redemptions or losses, it may realize gains and make distributions.

- Small or illiquid funds. A small ETF with limited primary market activity may have fewer opportunities to use in-kind redemptions to manage basis. If it must sell holdings to meet cash needs, gains can be realized.

- Corporate actions and index events. Mergers, spin-offs, or deletions from an index can force the ETF to sell positions. Sometimes the portfolio receives cash in a takeover that crystallizes gains.

- Foreign markets and withholding. International equity ETFs often face withholding taxes on dividends that are not eliminated by the ETF structure. In-kind mechanics also can be more complex across markets, and baskets may require cash substitutions.

- Bond ETFs. While bond ETFs can avoid capital gains distributions in many cases, the primary tax burden typically comes from ordinary interest income. Tax efficiency in the capital gains sense does not change the character of income.

There is also an operational phenomenon sometimes called a heartbeat. Large creations followed by large redemptions in a short window can be used to reposition the portfolio and distribute low-basis securities through redemptions. The practice relies on the same in-kind rules and has drawn regulatory attention over the years. The legal framework permits in-kind redemptions, and funds are expected to have policies governing basket construction and fair treatment. The important point for students of market structure is that this activity illustrates how the ETF mechanism can be used to manage embedded gains in a rules-based manner.

Structural Variations and Tax Consequences

Not all ETFs share the same tax profile. Structure and underlying exposure matter. Common U.S. types include:

- Open-end 1940 Act equity and bond ETFs. These comprise the majority of ETFs. They can pass through qualified dividend income, ordinary income, and capital gains distributions. They typically use in-kind baskets and are the canonical example of tax-efficient funds.

- Unit investment trusts. Less common in new launches. UITs have constraints on portfolio management and may have different distribution mechanics, but their in-kind processes can still support tax efficiency for capital gains.

- Commodity grantor trusts. Some physical commodity ETFs, such as those holding gold bars, are structured as grantor trusts. For U.S. taxpayers, long-term gains on certain precious metals held via a grantor trust can be taxed at the collectibles rate, which can be higher than the standard long-term capital gains rate. These vehicles typically do not produce qualified dividends.

- Commodity pool partnerships. ETFs that gain exposure through futures may be organized as publicly traded partnerships and issue Schedule K-1 to investors. U.S. tax rules often apply Section 1256 60 or 40 treatment to many futures positions, with blended rates for gains and losses and mark-to-market at year-end. The in-kind equity mechanism does not directly apply to futures positions, so tax efficiency claims should be considered in light of the partnership and derivatives rules.

- Exchange-traded notes. ETNs are unsecured debt obligations of an issuing bank that promise the return of an index, less fees. There are no underlying securities held in a pool. Taxation often occurs when the investor sells the note or at maturity, and periodic coupons, if any, are taxed according to their character. ETNs can be tax efficient with respect to interim capital gains distributions because they are not pooled portfolios, but they add issuer credit risk and different tax timing features.

These distinctions show that tax efficiency is not a blanket label. It depends on the legal form of the product and the instruments used to achieve exposure.

The Role of Custom Baskets and Lot Selection

Custom baskets allow portfolio managers to deviate from pro rata delivery when doing creations and redemptions. With proper oversight and documentation, managers can choose which exact tax lots to include in a redemption basket. Delivering lots with the lowest cost basis maximizes the removal of embedded gains. Some funds also use tax-lot selection when they must trade in the market, selling higher-basis shares to minimize realized gains. These tools sit alongside other portfolio considerations such as liquidity, tracking error to the index, and transaction costs.

Regulatory changes have influenced this area. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 6c-11, which standardized ETF regulation and facilitated broader use of custom baskets subject to written policies and procedures. The emphasis is on fair treatment, transparency to authorized participants, and risk management. The practical result has been greater flexibility for ETFs to manage tax basis without compromising the tracking of the underlying index.

Real-World Context: Year-End Distributions

Each year, funds evaluate realized gains and losses and determine whether they must distribute net capital gains to shareholders to maintain their tax status. Many mutual funds announce sizable year-end capital gains distributions after periods of market appreciation or investor outflows. By contrast, large broad-market ETFs often announce zero capital gains distributions because redemptions and lot management prevented net gains from building up inside the fund.

For example, consider an index ETF that experienced net inflows for most of the year and saw periodic redemptions by market makers during bouts of market stress. Throughout the year, the ETF handed out low-basis shares of long-held winners in redemption baskets. When the index rebalanced in December and the ETF needed to exit a few positions, the gains realized on those sales were small because the most appreciated lots had already been delivered in prior redemptions. The fund distributed only dividends from the underlying stocks, categorized according to their tax character, and no capital gains distribution was required.

International Perspectives

Tax treatment varies across jurisdictions. Some countries have different rules for in-kind transactions or for the taxation of funds generally. In certain markets, ETFs do not enjoy the same degree of capital gains distribution minimization as in the United States. Additionally, cross-border withholding on dividends from foreign holdings affects the income investors receive and may or may not be creditable depending on local law and fund elections.

Domicile also matters. An ETF listed in one country may be domiciled in another, which can change tax treaty access and investor reporting. Investors commonly encounter Ireland-domiciled ETFs in Europe, U.S.-domiciled ETFs in the United States, and Canada-domiciled ETFs in Canada, each with distinct reporting and withholding frameworks. These differences do not negate the concept of tax efficiency but shape how and where it operates.

Interactions with Index Tracking

ETF managers balance tax considerations with tracking performance. The primary objective for an index ETF is to follow the index within a tight tracking error band. Custom baskets, in-kind redemptions, and lot selection are used to achieve this while minimizing realized gains. If the index deletes a security, the fund must remove it as well, which can trigger sales. Managers can sometimes pair sales with redemptions that remove low-basis lots in related names or use temporary derivatives to align exposure before in-kind adjustments. The point is that tax efficiency is part of the toolkit, not a separate objective that overrides the mandate to track the index.

Costs and Implementation Frictions

Tax efficiency is not costless. Coordinating primary market flows, building baskets, and monitoring tax lots requires infrastructure and expertise. ETFs also incur transaction costs when trading in the secondary market to manage cash flows, corporate actions, and index changes. Market conditions can affect the feasibility of in-kind redemptions. In stressed markets, delivering certain securities may be operationally difficult, which can reduce reliance on in-kind baskets.

Another practical friction is the minimum block size for creations and redemptions. Because only large blocks can be exchanged in kind, small day-to-day investor flows are handled in the secondary market without affecting the fund’s portfolio. This is helpful for taxes, since it prevents routine purchases and sales from passing through to the portfolio. It also means the fund relies on authorized participants to intermediate between end investors and the primary market.

Reporting and Investor Experience

From the investor’s perspective, the hallmark of ETF tax efficiency is receiving few or no capital gains distributions relative to a comparable mutual fund. Income distributions continue, and their character depends on the underlying holdings. U.S. investors typically receive Form 1099-DIV showing ordinary income, qualified dividend income, and any capital gains distributions. Sales of ETF shares appear on Form 1099-B. Commodity pool partnerships may issue Schedule K-1, and ETNs have debt-like reporting.

At the fund level, portfolio managers track realized and unrealized gains, gain-loss carryforwards, and wash sale adjustments. Wash sale rules apply to sales inside the fund, but in-kind redemptions are not sales for tax purposes, which is another reason they are useful. If a fund realizes losses, it can carry them forward to offset future gains, further reducing the chance of a distribution in later years.

Limitations and Evolving Rules

Tax codes and securities regulations evolve. The ETF mechanism depends on rules that treat in-kind redemptions favorably at the fund level and allow flexibility in basket construction. Regulatory bodies also monitor how funds use these tools to ensure fair practices and appropriate disclosures. Market participants should expect continued refinement of operational guidelines, particularly around custom baskets and the use of derivatives within ETFs.

Putting the Concept in Context

ETF tax efficiency belongs to a larger story about how modern market structure channels liquidity. The presence of authorized participants and market makers creates a continuous arbitrage between an ETF and its underlying holdings. That arbitrage facilitates in-kind flows, which in turn allow funds to manage embedded gains. The same structure that keeps ETF prices close to net asset value is the structure that delivers tax benefits at the fund level under current U.S. law.

It is best viewed as a structural attribute, not a promise. The more an ETF can use in-kind redemptions, select tax lots, and avoid forced cash sales, the more likely it is to avoid distributing capital gains. Asset class, portfolio turnover, fund size, and regulatory regime all influence the outcome.

Key Takeaways

- ETF tax efficiency refers to the tendency of many ETFs, especially U.S. equity index funds, to distribute few capital gains due to in-kind creation and redemption processes.

- The mechanism works through the ETF’s primary market, where delivering low-basis securities in kind can remove embedded gains without realizing them at the fund level.

- Tax efficiency addresses fund-level capital gains distributions but does not eliminate taxes on dividends, interest, or gains when investors sell ETF shares.

- Structure matters: open-end 1940 Act ETFs, commodity grantor trusts, commodity pool partnerships, and ETNs have different tax characteristics and investor reporting.

- Tax outcomes vary with turnover, asset class, liquidity, and jurisdiction, so efficiency is common but not universal or guaranteed.