Cash flow sits at the center of fundamental analysis because it connects reported earnings to the actual liquidity a business generates. Two measures frequently used in valuation work are operating cash flow and free cash flow. They sound similar but answer different economic questions. Operating cash flow gauges the cash produced by core operations before long-term investment and financing choices. Free cash flow estimates the residual cash after funding the reinvestment required to sustain and grow the business. Understanding both, and when to use each, improves the quality of intrinsic value assessments.

Where These Measures Sit in the Financial Statements

The cash flow statement groups activity into operating, investing, and financing sections. Operating cash flow, often labeled cash flow from operations or CFO, appears in the operating section. It starts with net income and adjusts for non-cash items and changes in working capital. Investing cash flows include capital expenditures for property, plant, and equipment, as well as acquisitions and proceeds from asset sales. Financing cash flows capture debt issuance and repayment, dividends, and share transactions.

Free cash flow is not a required subtotal under accounting standards. It is constructed by analysts from items that already appear on the cash flow statement. Most commonly, free cash flow equals operating cash flow minus capital expenditures. That simple form is a proxy that captures the funds available after routine reinvestment. In valuation work, the definition is often refined to align with the specific cash flows attributable to the enterprise as a whole or to equity holders.

Defining Operating Cash Flow

Operating cash flow measures the cash generated by the company’s regular business activities within a reporting period. Under a typical reconciliation method, it begins with net income and then adjusts for:

- Non-cash expenses such as depreciation, amortization, and impairment charges.

- Non-cash income such as certain gains that did not involve current-period cash.

- Changes in operating working capital accounts, including receivables, inventories, payables, and other operating accruals.

The purpose of these adjustments is to convert accrual-based earnings into cash terms. If revenues were recognized but customers have not yet paid, receivables rise and operating cash flow falls relative to net income. If inventory was produced but not sold, cash outflow occurs without revenue recognition, which lowers operating cash flow. Conversely, an increase in payables means the firm postponed cash payments to suppliers, which lifts operating cash flow.

Accounting frameworks also influence classification. Under US GAAP, interest paid and interest received are generally included in operating cash flows, and income taxes paid appear in operating cash flows. Under IFRS, firms may classify interest paid and interest received as operating or financing and investing, subject to policy choice, which can complicate cross-company comparisons. Lease accounting adds another layer. Under US GAAP, operating leases typically result in cash payments that reduce operating cash flow, while for finance leases the interest portion is operating and the principal portion is financing. Under IFRS, the principal portion of lease payments is usually financing, while classification of interest paid can vary by policy. When comparing operating cash flow across firms, it is important to understand these policy choices.

Defining Free Cash Flow

Free cash flow represents cash available after the business funds the investments needed to maintain and expand its productive capacity. There are two main variants, which align with different valuation perspectives.

Free Cash Flow to the Firm

Free cash flow to the firm, often abbreviated FCFF, measures cash available to all providers of capital, both debt and equity, after necessary reinvestment. A common formulation begins with operating income and removes the effect of capital structure to isolate the enterprise’s cash generation. A typical expression is operating income after tax plus non-cash charges minus capital expenditures minus the increase in operating working capital. Many analysts implement FCFF using a shortcut starting from operating cash flow. Because operating cash flow under US GAAP includes interest paid, analysts add back interest net of the tax shield and then subtract capital expenditures and working capital increases. The goal is to reflect cash generated by operations regardless of how the business is financed.

Free Cash Flow to Equity

Free cash flow to equity, often abbreviated FCFE, measures cash available to common shareholders after funding reinvestment and after considering net debt transactions. A common expression starts from operating cash flow, subtracts capital expenditures, adjusts for changes in working capital if not already captured consistently, and then adds net borrowing, which is new debt raised minus debt repaid. If the firm issues more debt than it repays, equity holders effectively receive additional cash capacity. If the firm reduces debt, equity holders have less residual cash in that period.

Both FCFF and FCFE can be calculated in multiple equivalent ways as long as the classification of interest, taxes, and working capital is handled consistently. The chosen method should match the valuation framework. When estimating enterprise value, FCFF is used and the present value of those flows corresponds to the value available to both debt and equity. When estimating equity value directly, FCFE is used and the present value corresponds to the residual for shareholders.

Why the Distinction Matters for Long-term Valuation

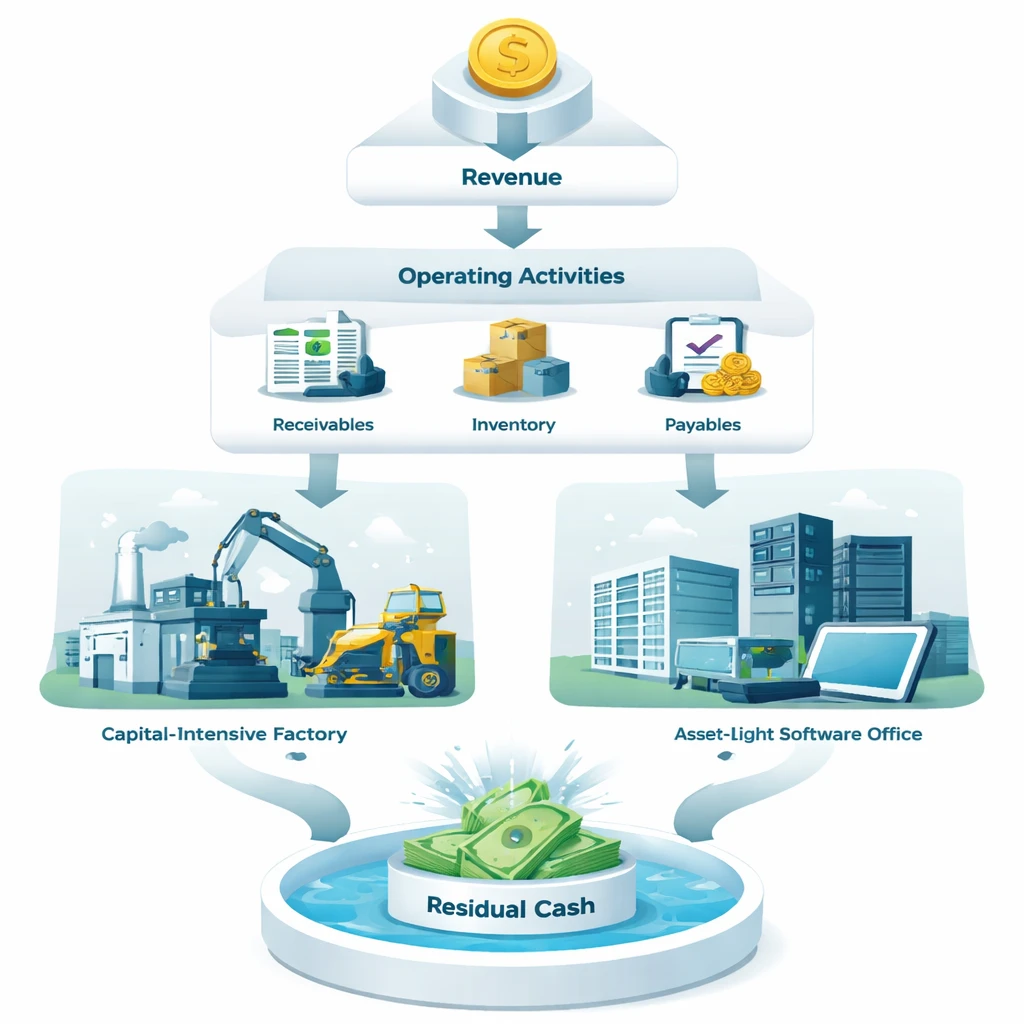

Operating cash flow indicates whether a business converts its revenue and earnings into cash in the near term. Free cash flow indicates the cash that remains after the business funds its reinvestment needs. A firm can show strong operating cash flow while generating little or no free cash flow if it operates in a capital-intensive industry and must reinvest heavily. Conversely, an asset-light firm may display modest operating cash flow but a high conversion to free cash flow, because capital needs are minimal.

Intrinsic value depends on the cash the business can deliver to capital providers over time. Valuation methods such as discounted cash flow models translate forecasts of future cash flows into present value. In these models, free cash flow is the central input. Operating cash flow is diagnostic. It helps assess the quality of earnings and the cash conversion dynamics that underpin free cash flow, but it is not itself the quantity that accrues to capital providers after reinvestment. This is why analysts often build bridge schedules that link net income to operating cash flow and then to free cash flow. The bridge reveals where cash is absorbed or released, whether from working capital swings, elevating capital expenditures, or one-off items.

A Practical Computation Walk-through

Consider a simplified manufacturing firm for a single year. The income statement shows revenue of 1,000, operating income of 120, interest expense of 20, taxes of 20, and net income of 80. The cash flow statement reveals depreciation of 50, an increase in inventories and receivables net of payables of 40, capital expenditures of 90, and no acquisitions. Debt levels are unchanged.

Operating cash flow is calculated as net income plus non-cash charges plus or minus working capital changes. That is 80 plus 50 minus 40, which equals 90. This indicates the core operations produced 90 in cash after reflecting the period’s working capital investment.

Free cash flow to the firm can be approximated from operating cash flow by removing financing effects and subtracting capital expenditures. The financing effect embedded in operating cash flow is interest paid. If the tax rate is 20 percent, the after-tax interest add-back is 20 times one minus 0.20, which equals 16. FCFF is approximately 90 plus 16 minus 90, which equals 16. This is a small residual because the firm undertook a heavy capital program relative to current operating cash generation.

Free cash flow to equity starts from operating cash flow and subtracts capital expenditures, then adjusts for net borrowing. In this example there is no net borrowing, so FCFE is 90 minus 90, which equals 0. Shareholders received no residual cash this year because the firm reinvested all operating cash into capital assets.

This simple bridge illustrates why operating cash flow and free cash flow diverge. Operating cash flow looked comfortable at 90. After funding the capital program, little or nothing remained. That divergence may be temporary if capital spending is front-loaded and yields higher operating cash flow later. It may also be structural if the business model requires continual heavy reinvestment.

Interpreting Cash Flow Quality

The reliability of operating cash flow and free cash flow depends on the nature of the adjustments and the stability of the components.

Non-cash items can be complex. Depreciation and amortization are straightforward add-backs, but impairment charges and fair value gains or losses can be more volatile. Stock-based compensation increases operating cash flow under the indirect method because it is a non-cash expense, yet it can dilute equity over time. Analysts often assess stock-based compensation alongside share repurchases and issuance to understand the net effect on owners.

Working capital is frequently the largest source of short-term variability. Rapid growth often consumes cash as receivables and inventory rise faster than payables. Seasonality can skew single-period readings. Retailers, for instance, typically build inventory before peak selling seasons, which depresses operating cash flow in build periods and lifts it during sell-down periods. One period rarely tells the full story, so trailing and forward views help separate noise from trend.

Capital expenditures require careful interpretation. Not all capital spending serves the same purpose. Maintenance capital expenditures keep assets in their current productive state, while growth capital expenditures expand capacity or capability. Financial statements rarely split these amounts explicitly. Management commentary and supplemental disclosures can provide hints, such as discussions of capacity additions or new store openings. The distinction matters because free cash flow after maintenance capital expenditures speaks to the cash the existing asset base can produce. Free cash flow after growth capital expenditures captures strategic expansion choices and can be lower during build phases.

Acquisitions appear under investing cash flows but are not part of the typical free cash flow definition that subtracts only capital expenditures. Analysts handle acquisitions in different ways depending on the purpose of the analysis. In valuation, the forecast period may explicitly include expected acquisition spending if acquisitions are part of the business model, but care must be taken to avoid double counting growth that also relies on acquisition spending.

Leases affect comparability across time and among firms. Under current standards, many leases are capitalized, creating a lease liability and right-of-use asset. The cash payments may be split between operating and financing sections depending on the accounting framework and lease type. As a result, two firms with similar economics could report different patterns of operating cash flow and capital expenditures. Reading footnotes on lease commitments and policies helps normalize comparisons.

How Operating and Free Cash Flow Inform Valuation

Discounted cash flow analysis projects future free cash flows and discounts them at a rate that reflects the risk and capital structure. The distinction between FCFF and FCFE dictates the discount rate and the form of the valuation. FCFF is discounted at the weighted average cost of capital and yields an enterprise value. Subtracting net debt and other claims then yields equity value. FCFE is discounted at the cost of equity and leads directly to equity value. Both approaches converge if implemented consistently, but practical modeling choices often make FCFF more straightforward for companies with changing leverage.

Operating cash flow supports the construction of these forecasts in several ways. First, it reveals the historical cash conversion of earnings. Persistent gaps between net income and operating cash flow can signal aggressive revenue recognition, working capital strain, or the influence of non-cash items. Second, it helps calibrate working capital assumptions. Improvements in receivable collections or inventory turnover can release cash and lift near-term free cash flow without requiring margin changes. Third, it contextualizes capital intensity. The ratio of capital expenditures to depreciation, and the trajectory of that ratio, hint at whether the asset base is in maintenance mode or expansion mode.

Free cash flow sits at the heart of the value narrative. Over long horizons, firms that can sustain high returns on invested capital while reinvesting meaningfully often grow free cash flow at attractive rates. Firms with low capital intensity and stable demand may convert a large share of operating cash flow into free cash flow. In contrast, firms in commodity or infrastructure-heavy sectors may display lower free cash flow during investment cycles, even when operating cash flow appears healthy. For long-term valuation, the pattern and durability of free cash flow matter more than any one period’s magnitude.

Sector Patterns and Market Context

Consider two stylized cases. A regulated utility earns predictable operating income but must replace and upgrade equipment continuously. It generates steady operating cash flow, yet capital expenditures absorb a significant portion every year. Free cash flow tends to be modest and often turns negative during infrastructure build-outs. Investors in such sectors often focus on the stability of operating cash flow and the recoverability of investment through regulated pricing, but free cash flow variability is a feature of the model, not necessarily a signal of distress.

Now consider a software company that delivers services through an established cloud platform. Operating cash flow is shaped by revenue growth, high gross margins, and billing practices that may generate deferred revenue inflows. Capital expenditures are comparatively low because the company rents infrastructure capacity under long-term contracts rather than owning physical assets. Free cash flow conversion is high in many years, even if reported earnings are modest due to stock-based compensation or amortization of intangibles. Here, free cash flow provides a clearer picture of economic capacity than net income, while operating cash flow helps diagnose the influence of working capital timing, such as large annual billings that seasonally inflate deferred revenue.

A retailer falls somewhere between these extremes. Operating cash flow fluctuates with inventory cycles. Capital expenditures include new store openings and remodels. Working capital improvements, such as better inventory management, can release cash and expand free cash flow without meaningful changes in sales growth. This interaction of working capital and capital expenditures often drives the difference between operating and free cash flow in consumer sectors.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Several recurring issues complicate the interpretation of operating and free cash flow:

- Mixing definitions. If operating cash flow includes interest paid, and the goal is to estimate FCFF, the after-tax interest should be added back before subtracting capital expenditures. Failing to adjust yields a figure closer to FCFE but not exactly equal, which can misalign with the discount rate in valuation.

- Ignoring maintenance versus growth capital expenditures. Treating all capital spending as discretionary can overstate free cash flow potential. Maintenance requirements can be significant, particularly in capital-intensive industries.

- Relying on a single period with unusual working capital movement. Short-term cash releases from lowering inventory or stretching payables can flatter operating cash flow and free cash flow. These effects often reverse in subsequent periods.

- Overlooking stock-based compensation and share count effects. While non-cash and thus added back in operating cash flow, stock-based awards may dilute owners. Free cash flow per share trends are sensitive to this dynamic.

- Inconsistent treatment of leases and interest under different accounting regimes. Without normalization, cross-firm comparisons can mislead.

From Historical Measures to Forecasts

Fundamental analysis uses history to inform expectations. The translation from historical operating cash flow and capital expenditures to projected free cash flow requires explicit assumptions about growth, margins, capital intensity, and working capital efficiency. Historical averages are a starting point, but structural changes often alter the path. For instance, a maturing manufacturer may see capital expenditures decline toward depreciation as expansion slows, lifting free cash flow even if operating cash flow grows modestly. A company that reconfigures its supply chain might reduce days in inventory, freeing cash and improving free cash flow conversion at a given level of sales.

Analysts frequently track ratios that summarize these relationships. Examples include free cash flow margin, defined as free cash flow divided by revenue, and cash conversion, often defined as free cash flow divided by net income or by operating cash flow. These ratios vary by industry. Sustained improvement can point to operational enhancements or favorable business mix shifts. Deterioration can signal rising capital intensity, more challenging credit terms with customers, or inventory management issues.

Assessing Sustainability

Not all free cash flow is equally sustainable. A period with unusually low capital expenditures might show elevated free cash flow, but deferred maintenance could require higher spending later. A release of working capital might be a one-time benefit if it reflects moving to leaner inventory targets, but it cannot be repeated indefinitely. Conversely, negative free cash flow during a build phase might be a rational investment that sets up higher operating cash flow and free cash flow in future years. Distinguishing between transitory and structural drivers is central to credible valuation.

Tax considerations also matter. Operating cash flow reflects cash taxes paid, which can be lower than statutory rates due to loss carryforwards, credits, or accelerated depreciation. In forward-looking valuation models, analysts often normalize tax rates toward a long-run expectation. This normalization affects the bridge from operating income to free cash flow and helps avoid overstating value based on temporary tax advantages.

Linking Operating Cash Flow to Return on Capital

Return on invested capital is a performance measure that connects profits to the asset base required to produce them. Operating cash flow and free cash flow offer a cash perspective on the same relationship. If a firm generates strong operating cash flow relative to its invested capital and does not need to reinvest heavily, the result is ample free cash flow. If operating cash flow is strong but the asset base must be renewed frequently, free cash flow may remain constrained. Examining operating cash flow alongside capital expenditures and working capital intensity provides a practical view of how a given return on capital profile translates into free cash flow over time.

Real-world Illustration of Dynamics Over Time

Imagine a cyclical equipment supplier over a four-year cycle. In year one, orders surge, receivables and inventory build, and operating cash flow lags net income because working capital consumes cash. Capital expenditures also rise to expand capacity. Free cash flow turns negative. In year two, the firm benefits from the expanded base, operating cash flow climbs as sales convert to cash, but capital expenditures remain elevated as projects complete. Free cash flow is near break-even. In year three, demand normalizes, working capital releases cash as receivables are collected and inventory is sold down. Operating cash flow jumps, and with lower capital expenditures, free cash flow rises sharply. In year four, replacement needs drive maintenance capital expenditures back toward depreciation and free cash flow settles at a level that matches the sustainable operating cash flow of the existing footprint. The multi-year path illustrates how both measures are needed to understand where the firm stands in the cycle and what part of cash generation is likely to persist.

What to Review in Disclosures

Financial statements and footnotes often provide detail that improves the interpretation of operating and free cash flow:

- Reconciliations in the operating cash flow section that break out key working capital components and unusual non-cash items.

- Capital expenditure detail by category, geography, or project, when available, which can help infer maintenance versus growth spending.

- Lease commitments, purchase obligations, and policies for classifying interest and lease cash flows.

- Stock-based compensation schedules and share count roll-forwards to gauge dilution relative to free cash flow per share.

- Tax disclosures, including deferred tax assets and effective rate bridges, to judge how cash taxes might evolve.

Bringing It Together for Intrinsic Value Work

Operating cash flow and free cash flow are complementary. Operating cash flow is a near-term gauge of the cash engine of the business. Free cash flow is the measure that aligns directly with the cash available to capital providers after the business has funded its required reinvestment. In intrinsic value analysis, operating cash flow supports the diagnosis and calibration of key drivers, while free cash flow provides the basis for valuation. Credible analysis treats both as parts of a system and pays attention to accounting classifications, the economic purpose of investment spending, and the pattern of working capital movements. The goal is not to identify a single number, but to understand the mechanisms that turn revenue into durable, distributable cash over time.

Key Takeaways

- Operating cash flow captures cash generated by core operations after non-cash adjustments and working capital changes, while free cash flow reflects the residual after funding necessary reinvestment.

- Free cash flow comes in two primary forms. FCFF relates to the enterprise and aligns with enterprise value, while FCFE relates to equity holders and aligns with equity value.

- The distinction matters because operating cash flow is diagnostic and free cash flow is the basis of discounted cash flow valuation.

- Comparability requires attention to accounting classifications, lease treatment, taxes, and the mix of maintenance versus growth capital expenditures.

- Short-term swings in working capital and episodic capital projects can obscure underlying trends. Multi-period analysis provides a clearer view of sustainable free cash flow.